It may appear that drinking at home was not a thing in August, but if truth be known we were trying to drink up the sort of wines which either I didn’t want to lug up to Scotland along with a few wines I’d bought several bottles of for summer consumption. We are left with only six I want to tell you about and they come from South Africa, Hungary, Provence, Burgenland, Franconia and The Loire.

Luuks 2020, Blank Bottle Winery (Stellenbosch, South Africa)

I bought several bottles of this over a couple of orders and I’m really pleased I did. It’s a new cuvée from Pieter Walser, and “luuks” means “luxury” in Afrikaans, quite apt. It was the first time Pieter had been able to afford a brand-new barrel, sourced from Burgundy, and this is the result.

The fruit chosen was, perhaps unsurprisingly, Chardonnay from Stellenbosch. Pieter has made a shockingly good wine from it. Interestingly, the alcohol here is not what you’d expect. Some of Pieter’s wines can, how can I put it, creep up on you, and surely Chardonnay might be a candidate for that effect. But no, this shows a very restrained 12.5% abv.

The wine is obviously young at more-or-less two years old, but despite a buttery, toasty, side to it, we also have bright citrus acidity which both balances the oak, and makes the wine so nice to drink now that I’m not sure keeping it will bring a great deal more to the game. It will doubtless broaden but it’s so alive right now, in the way that I described Gut Oggau’s wines recently.

I would say that this is probably the best new Blank Bottle cuvée I’ve tasted for a while, despite the incredibly high standards this wonderful, slightly under the radar, South African producer adheres to. I really like this.

As always, I think all of Pieter’s wines are amazing value. Imported by Swig Wines, this Came from Butlers Wine Cellar in Brighton.

Eastern Accents 2020, Annamária Réka-Koncz (Eastern Hungary)

I’ve written about this producer many times, so many readers will know of my special affinity for these wines. I drank, and wrote about, the previous vintage of Eastern Accents just over twelve months ago, so I have no worries about plugging my first bottle of the 2020.

The key to Annamária’s wines begins with old vines, around 40-to-60 years old. They are situated on what is known as the Northern Great Plain, close to Barabás, right up on the Ukrainian border. This is obviously not one of Hungary’s more famous viticultural regions, but the terroir is not massively dissimilar to that in Tokaj, which is not all that far away.

The blend in this bottling is 70% Harslevelü with 30% of Annamária’s secret weapon, the Királyleányka variety, better known perhaps as Fetească Regală to those familiar with the wines of Romania. The grapes see a five-day maceration on skins, so this is a skin contact wine. This is followed by a carbonic fermentation (my notes on the 2019 say semi-carbonic) in tank (the cuvée sees no wood).

The result is massively fruity, fresh and easy to drink but there is undoubtedly mineral texture from skin contact and lees. There’s a lovely bite to the finish which adds considerable interest. Apart from describing this wine as gorgeous, I’d also call it “precise”. Only 2,028 bottles were made of this. It is both a good introduction to the Réka-Koncz range, and to skin contact wines in general. Although it is darkish in colour, it’s not an especially tannic amber wine, compared to many.

Annamária Réka-Koncz is imported here in the UK by Basket Press Wines.

Château Simone Rosé 2020, Famille Rougier (Palette, France)

Palette is a tiny appellation in Provence, tucked away in the hills close to Aix-en-Provence. It’s a place you might swish past on the Autoroute, which passes close by, but I’ve never been able to spot any vines. I tried to find the place once, many decades ago, and failed. As far as I know there are just two producers in Palette and Simone is the famous one. It has been home to the Rougier family since the 1830s. They happen to make my favourite Porvençal pink wine (along with fine red and white), and I’d rarely buy a case from Yapp Brothers back in the day without adding in a bottle.

However, I do have a confession. Simone Rosé demands bottle age, pretty much unlike (almost) any other pink wine from this broad region, known for its “best drunk on holiday” brands and only a small group of artisan estates. Having not drunk Simone for a long while some impulse got the better of me. I should have kept this bottle longer, but at least I have the experience to assess it as if I were at a tasting. At £40/bottle now, it was a shame to open it as early as I did.

This is on the darker side for a Rosé, quite a distance removed from the pale numbers so fashionable these days, from the coastal seafood restaurants to a supermarket near you. Its colour is in the same sort of zone as Tavel. The grapes grown at Simone are a long list of the familiar and the unfamiliar. Grenache and Mourvèdre form the base of the pink wine, and they sit alongside the likes of Manoscan, Castet, Muscatel (sic), and Syrah. They are co-planted on limestone scree on the Montaiguet Massif.

Partially destemmed, the grapes undergo a long cuvaison of nine months before going into used oak. The result certainly has body and structure closer to a red wine, yet its character, although partially unique, does point towards a white wine in terms of freshness and acid balance. I think the red fruits come through best on the nose, and Yapp’s use “purity” as a description, which is apt. The palate adds in herbal touches with a little spice. They suggest keeping it 2-3 years, I reckon five years is not too long. Certainly drinking it at two years old was at the beginning of the window, but I think that unless you actively dislike the darker, actually more food-friendly style of Rosé, you will find this an impressive wine.

Although previously purchased from Yapp Brothers in Mere, Wiltshire, this bottle came from The Solent Cellar, in Lymington (Hants).

Neuburger 2018, Joiseph (Burgenland, Austria)

Joiseph is partly named after Jois, a village towards the top of Burgenland’s Neusiedlersee. Luka Zeichmann is the young star who makes the wines. He joined up with business partners Alex Kagl and Richard Artner, who both tend the vines, only in 2015. Jois is where you’ll find the vines, but confusingly the cellars are at Unterpullendorf, a good hour away to the south.

When they began there was under a hectare of vines, split into five tiny parcels. They have grown quite a bit since then…to just under six hectares. The vineyards are mostly on a mix of limestone with shale, which you probably know is the common rock type up here on the southeast-facing Leithaberg Hills which surround the lake’s northwestern side.

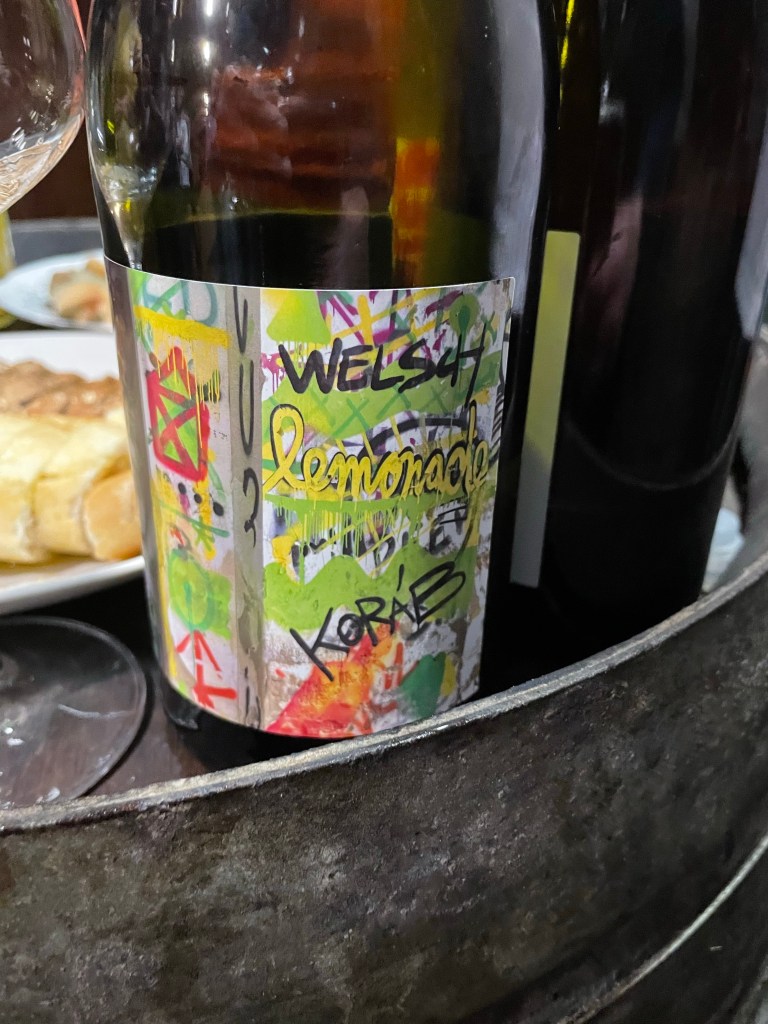

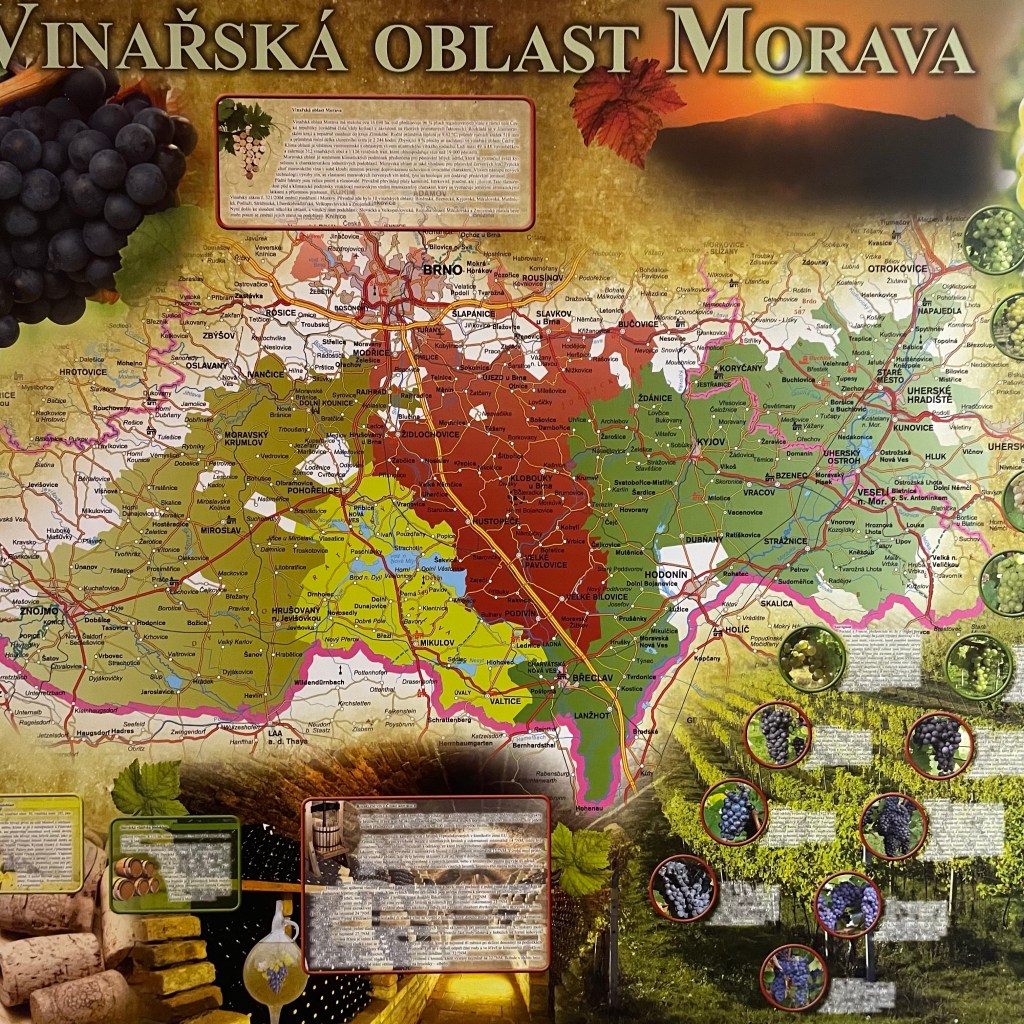

Grapes cover all the usual Burgenland bases and many Joiseph wines are blends. This, however, is a single variety seen all too little even in its homeland. I think I was lucky to get a bottle because the various importers to different countries rarely seem to have any. Neuburger is a white variety, a cross between Roter Veltliner and Silvaner. Those who don’t know it by this name might have come across it in the Upper Mosel (Germany) or even Luxembourg, where it goes by the name of Elbling. The eagle-eyed will have noticed that I also tasted the variety in Moravia this summer (Osička blends it with MT in his “Milerka”, Stavek uses it in field blends, Krasna Hora in their entry level “La Blanca”, but even better, Petr Koráb makes a varietal Neuburger which is well worth seeking out).

Even in Germany Neuburger is not very well known, and certainly lauded by few wine writers. Of course, give an unloved variety to a star winemaker and you are likely to taste something interesting. A few winemakers in Austria are treating it with respect, rather like the mini-renaissance of Räuschling in Switzerland.

All the Joiseph wines are completely natural. They used to joke that the only vineyard equipment they owned were wellingtons and secateurs. Not totally true, but they don’t own a tractor, often the first toy new viticulturalists buy with their first agri-loan.

Anyway, what does this taste like? Rather good I must say. The big impression comes from its salinity. It has that salty/savoury taste and a bit of texture. This is balanced by different fruit flavours. Pear dominates, perhaps, but there’s a touch of crisp apple and I am sure I got a hint of pineapple in the overall freshness. This isn’t “fane wane”, but it’s a damned interesting bottle. A mere 800 of them were made.

Joiseph wines come into the UK via the excellent small importer, Modal Wines.

Rouge 2019, Max Sein Wein (Franconia, Germany)

The Max in question is Max Baumann, who runs his family’s vineyard at Dertingen, in that part of Baden known in anglophone countries as Franconia. Here, he farms around 3.5-ha of vines which are up to 60-years-old on limestone with a little red sandstone. All farming is organic and the wines are made with minimal interventions.

For the reds Max has plots of Pinot Noir and Meunier, preferring to use the French nomenclature for Spätburgunder and Schwarzriesling. Rouge 2019 has a majority of (Pinot) Meunier blended with Pinot Noir. He handles this variety, which is now getting more attention here, not just as fruit to slosh into Sekt, but really well as a still wine. The result is a wine with a smooth, fruity, mouthfeel, yet a haunting quality as the ethereal fruit of the Meunier comes through, matched on the bouquet by its lifted cherry scent. The Pinot Noir adds a more conventional cherries and berries fatness.

A delicious fruit bomb from an under-the-radar name, but my friend in Bordeaux (Feral Art et Vin) has also sold these wines and he’s got one of the best palates I know, and the best eye for a future German star bar none.

In the UK these wines come in via Basket Press Wines. They have a number of cuvées, including this one currently in its 2018 version, as well as 2019 guise. Around £28.

Saumur Blanc “Les Salles Martin” 2014, Antoine Sanzay (Loire, France)

When I purchased my first wines from Antoine, including this one, he was obviously set to be one of the up-and-coming names of Touraine. Now this Chenin Blanc is ready to drink, his star has risen. He’s based in the appellation of Saumur, at Varrains, just south of the famous Loire-side town itself. We are about five minutes by car from the large co-operative winery at St-Cyr-en-Bourg and much of the fruit from around here will go to that facility.

Antoine keeps alive artisan winemaking with a hillside plot at around 100 masl, which may have grown since, but last time I looked was a mere single hectare. He took over these vines terribly young after his father died unexpectedly, although it was his grandfather who had been the vigneron, sending his harvest to the co-operative as was the way back then.

Antoine had no experience, but he did get help and assistance from a rollcall of some of the biggest names from far and wide in artisan winemaking in the Loire (the Foucault brothers, the two Jo’s…Landron and Pithon, Bernard Baudry and others). With their inspiration he gained Ecocert biodynamic certification in 2014, at which point he began to bottle his wine himself.

Les Salles Martin is 100% Chenin from surprisingly young vines, possibly not quite ten years old. The fruit is aged in a mixture of barrique and foudre, yielding a wine with plenty of acidity and extract which I’d suggest needs some bottle age if you buy it on release. At a little less than eight years old, this is superb. Although I’d be in no immediate hurry to drink it, I’d say that this 2014 is in a very good place right now. It does taste youthful for Chenin, and there’s definitely, to my palate, some oak influence (despite having read that the oak back in 2014 was not new oak) there, but it’s just fantastically refreshing.

The acidity and vivacity in the wine comes obviously via the biodynamics, but it’s also worth noting that Antoine has avoided the malolactic here. From such a small plot of fairly young vines this is rather elegant as well. Lemon and grapefruit dominate, rather than the pear and quince, which may come later.

Another wine from The Solent Cellar. I think the importer is the Monmouth (Wales)-based Carte Blanche Wines.