It’s back to business as usual for my December wines. Whilst you will have read about the flashy bottles that were hedonistically consumed over Christmas and New Year in other places, here we have a selection which is more modest in price, though not really modest when it comes to quality and interest. Perhaps that’s no bad thing. In January you might wish to hear about good value bottles, rather than stuff you can’t afford even in the January Sales. Yes, I know they are sending you an email every day, but wine retailers really do not need a dry January.

Only one of the twelve wines which make up my two parts of last month’s Recent Wines costs more than £30, though if you are wondering what it is, it did make my “Wines of the Year” (it’s in Part 2 which follows). Here in Part 1, we have wines from Markgräferland (the southern part of Baden), Burgenland, Saint-Pourçain in the Upper Loire, Slovakia, North Canterbury (NZ), and the Vallée d’Aoste (to use this producer’s preferred labelling).

Markgräflerland Spätburgunder 2022, Martin Waßmer (Baden, Germany)

Most people are familiar with the central part of Baden north of Freiburg which embraces the Kaiserstuhl and Tuniberg, but the region stretches both north and south. In the far south, near to Basel and the Swiss border, we have Markgräflerland. Close to border at Efringen-Kirchen you will find one of my favourite German producers, Ziereisen. Around thirty kilometres to the north, between the Black Forest and the Rhine, at Bad Kruzingen, we have another excellent winemaker, Martin Waßmer.

Winemaking here is described as traditional, but it means indigenous yeasts, low intervention and oak ageing (though oak is not prominent in this wine). The overall impression is smooth cherry and strawberry fruit with darker notes beneath, complemented by a smoky finish. The fruit is ripe and alcohol is up at a balanced 13.5%, adding richness in the mouth. The wine isn’t especially complex, but it is very satisfying, and there is scope for development in bottle. You could keep some 3-4 years but it seemed a good choice for early December with the nights rapidly drawing in.

I think this counts as a genuine bargain. It cost just £16.50 from The Wine Society.

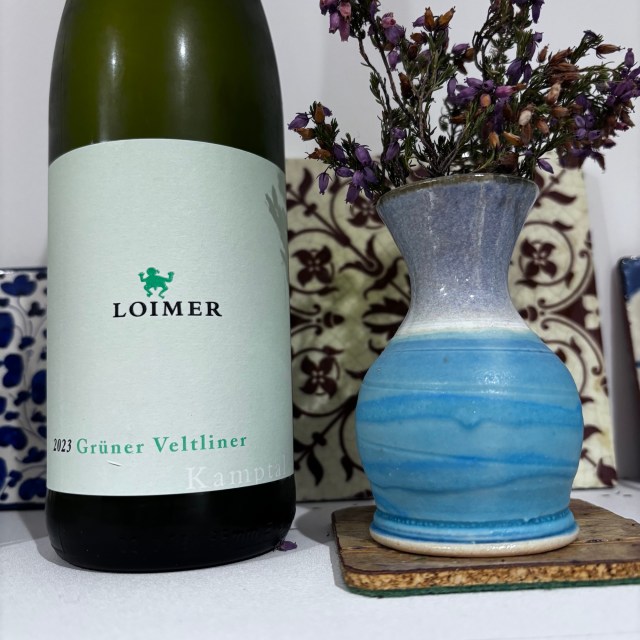

Grüner Veltliner 2024, Meinklang (Burgenland, Austria)

I go back a long way with Meinklang, largely through wines imported by Winemaker’s Club when they first opened. They were, and remain, at the centre of Austrian natural wine from their base at Pamhagen, where they have their famous “graupert” (unpruned) vines, a herd of prize cattle, and where they farm ancient grain cereals (from which they make a cracking beer if you ever see any). Pamhagen is close to the southeastern edge of the Neusiedlersee, and they also make fabulous wine further south, in Hungary, on the Somló Massif.

This Grüner Veltliner is from their entry level range, which I have mostly drunk before in restaurants. From the 2024 vintage, the fruit was spontaneously fermented following an early harvest, and direct-pressed before four months ageing on fine lees in stainless steel. It is softer than many Grüners, with apple and lemon with a little pear. Very easy to drink, but again, stunning value.

It was, in fact, a nice gift but it costs around £19, in this case from Cornelius in Edinburgh. It is also quite widely available throughout the UK, including at Cork & Cask in Edinburgh too. The importer is Vintage Roots.

Gamay 2023, Les Terres d’Ocre (Upper Loire, France)

This is one of a number of Loire wines which The Solent Cellar imports themselves (as they do wines from Chablis and Provence to name two more regions). All of them aim to combine quality and value from family estates. The result of them making the effort to ship the odd pallet is that we consumers get a bargain, so long as the wine lives up to its billing. This Gamay is made in the wider vine growing region of Saint-Pourçain, around the Allier tributary of the River Sioule, a very attractive part of the upper reaches of the Loire (into which the Allier flows, close to Nevers). It was a region which still felt pretty remote when I last visited its Yapp-imported cave co-operative in Saint-Pourçain itself.

Florent Barichard settled at Châtel-de-Neuvre, a ten-minute drive north of the town, in 2013. He works with partners Valérie and Eric Nesson. Florent has previous winemaking experience in New Zealand and South Africa. Together they make a range of wines, some I’ve had before and a Chardonnay/Tressallier (aka Sacy) blend which sits in my cellar. This Gamay is bottled as IGP, not AOP. The wine is organic, harvested manually, and made using native yeasts and sticking to a low sulphur regime.

The Gamay here is off local pink granite, which does give it, at least to my unscientific mind, some unique character. But of course, so do the amphorae (“jarres terre cuit”) it is made in. The bouquet has a nice freshness, with strawberry rather than cherry. The palate adds in some hints of dark fruits, combining with a little texture and spice. As I’m going through a bit of a reborn Gamay phase, I loved this. Just £12, from The Solent Cellar.

Jungberg Rizling Vlašský 2022, Vino Magula (Slovakia)

Magula is probably the estate I buy most wine from in Slovakia, although there are a couple which are better known. They are a fourth-generation family estate making natural wine at Suchá Nad Parnou, northeast of Bratislava in Southwestern Slovakia (close to Czech Moravia and relatively close to Vienna).

The grape variety here is one which we know better as Welschriesling. It is hand-picked from the single named site, Jungberg, and fermented in open vats on skins. The wine is a pale-yellow colour. The bouquet is a mix of floral elements and peachy fruit, whilst the palate is zesty and lively with a bit of peach stone texture, pear, herbs and even a hint of orange. Very refreshing at 11% abv, with less than 20mg/litre of added sulphur.

Magula is imported by Basket Press Wines. This cost me around £25. It may be currently out of stock, but they do highlight four excellent wines from this producer on their web site right now.

Pinot Noir “Zealandia” 2019, The Hermit Ram (North Canterbury, New Zealand)

For me, Theo Coles is one of New Zealand’s South Island star winemakers, making minimal intervention wines at North Canterbury, one of the country’s emerging quality wine regions. Canterbury is a large area around the South Island’s regional capital, Christchurch, but North Canterbury is over the Weka Pass from Canterbury’s best-known sub-region, Waipara (NOT to be confused with Wairarapa on the North Island, also a region producing fine Pinot Noir). North Canterbury is a sub-region becoming known for natural wines, the likes of Pyramid Valley and Bell Hill being established a little over 25 years ago. Theo arrived in 2012, to make Pinot Noir from Gareth Renowdon’s Limestone Hills Vineyard.

The Pinot Noir for Theo’s Zealandia cuvée comes from a number of organically farmed plots on limestone. The fruit is fermented with native yeasts after destemming. It sees six weeks on skins with only one punchdown. Ageing is in a lined Spanish clay amphora (“tinaja”), and it is of course bottled without fining or filtration, and with minimal added sulphur.

The colour is a striking, vibrant, violet. The bouquet shouts blackberry and blueberry. The palate is more of the same, textured (as with many wines which have seen clay vessels) and crunchy. Very “natural”, fresh, and if you noticed the vintage, no sign of tiredness yet. Theo really does craft magnificent wines.

Imported by Uncharted Wines, from whom you can buy direct, but mine came from Cork & Cask (Edinburgh).

Torrette 2022 Vallée d’Aoste AOC, Lo Triolet (Valle d’Aosta, Italy)

The dual language options available to winemakers in Italy’s Valle d’Aosta are evident here, but although this smallest of Italy’s appellations is very close to the French border, it always feels Italian to me. I will say that I have loved my visits here, both to Aosta itself (a town with several nice Roman era ruins and churches), and refuge walking up in the Gran Paradiso National Park, with its wonderful wildlife.

Torrette is made from Petit Rouge, a resolutely francophone grape variety ubiquitous in the western part of the valley. Marco Martin farms at Introd, not far from the exit to the Mont Blanc Tunnel. He began reviving his family’s old vineyards in 1988, first planting Pinot Grigio up at 800-900 masl, on sandy moraines of glacial origin. Viticulture is organic.

I am lucky to have drunk quite a lot of Aosta wines, having visited the region numerous times. Lo Triolet is the domaine I currently buy most of in the UK. At one time I’d have said I preferred their red Fumin and white Petite Arvine, but due initiallly to availability, the Torrette has risen in my estimation a great deal. This is definitely a mountain wine. It shows both red and darker fruits, nice unobtrusive tannins and a bitter bite on the finish adding a savoury quality. You probably wouldn’t guess this 2022 packs 14% alcohol. Calories very much needed in current temperatures, especially if you have been up in the mountains.

My bottle came once more from Solent Cellar. It cost a ridiculous £15 (I had to double check their web site). The abovementioned Pinot Grigio, sensibly labelled Pinot Gris, costs £22, and they have also stocked the Fumin and Petite Arvine in the past. Lo Triolet makes around a dozen different wines. Try any of them. The UK agent is Boutinot.