Back in June last year I reviewed a small book called Regenerative Viticulture by Dr Jamie Goode. It’s a fascinating work which, for those aware of one of winemaking’s buzz phrases, is pretty much self-explanatory in its title. In its introductory chapter the author plugs his future work, The New Viticulture. He says it will be “written in a style that’s accessible, but it will be a detailed, and quite lengthy book”. The former was the introduction, so to speak, to the current work which I think will prove to be profoundly important for any professionals working in wine, whether they make it or sell it, and to all serious students of the subject. It will also be of interest for all those like myself who are deeply emersed in a passion for not only wine, but the vineyards and cultures which create it.

This is a big work in several senses (160,000 words, I believe), and I can see why the author’s original stated aim, publication in late 2022, was a little ambitious. It finally saw publication in September this year (2023). I make no apology for only reviewing it now. In its four-hundred-plus pages there is a great deal of information, and a great deal of that information is science more easily understood by someone with greater knowledge of plant biology than I have (although Jamie has a PhD in plant biology, he told the truth about the “accessible style”, so don’t be put off by the science).

A detailed chapter-by-chapter analysis would be a very long exercise. What I plan to do is to identify some of the themes herein, some of which will be of great interest to the lay reader. I’ll also try to draw some of my own conclusions.

If you want to hear or read Jamie’s own words on what’s in the book you can easily see what he says on his web site, wineanorak.com . I hope I can add another perspective, especially as I am neither a scientist, nor someone involved in growing grapes, nor the making or selling of wine. I will also tell you why the majority of people who read Wideworldofwine fairly regularly will find The New Viticulture extremely worthwhile.

Viticulture has gone through some tough times since Neolithic cultures domesticated the vine, none more difficult than during the second half of the nineteenth century, when phylloxera and other vine pests and diseases almost wiped out the world’s vinifera vines. Today it is arguable that we are in an equally precarious period, caused primarily by Climate Chaos, but also the presence of a number of re-emergent vine pests and diseases, and by issues surrounding the use of synthetic treatments in the vineyard. These issues come on top of the economic woes facing vine growers and winemakers in general in a poor world economic climate.

The problems encountered in the latter half of the last century, which have only grown in their effect in the current one, have led to a new outlook from many wine producers, and an all-encompassing term of sustainability, or sustainable viticulture, is being used to point a way forward. This is not merely a term for people who want to save the planet. It is also a term equally as valid for those who wish to save their livelihoods. Self-preservation on a micro, as well as macro, level. It is perhaps within this context that we embark upon The New Viticulture.

Jamie gives us twenty-two chapters (apparently two further chapters had to be omitted “for space reasons”), beginning with his Introduction and finishing on page 439 with his Concluding Remarks. We begin by learning about this woodland tree climbing plant which was domesticated for its fruit and, quite possibly, fairly quickly after that, for its ability to make an alcoholic beverage both palatable and intoxicating.

After introducing the importance of climate to viticulture Jamie begins to go into detail about the nature of the vine and its interaction with the terroir in which it grows. One of the most topical parts of a vine’s environment is what the author describes as “the hidden half of nature”. As he states at the start of Chapter 4, “What is the biggest change in viticulture in the last decade? For me [and for me too, Jamie], the answer is clear. It’s the realization that soils matter”.

As he later quotes James Milton, not for the first time, “We’re not standing on dirt, but the rooftop of another kingdom”. The kingdom known as the rhizosphere must now be familiar to many for whom it meant little a couple of years ago, as we have come to understand more about what happens below ground and why this is of paramount importance to our ability to go on growing stuff.

The next few chapters cover rootstocks and grafting, ripening, yields, training and pruning and vine immunity. There’s a lot of science packed in here, and you’ll really develop a better understanding of things that you won’t even learn taking a degree in viticulture. But it’s not all pure science. For example, pruning and training is a fascinating subject within the context of climate chaos, something I’ve touched on myself in one of my most popular articles (Pergola Taught, 16/02/21).

Another super-topical chapter (11) is that on breeding new varieties (and rescuing old ones). If you want a re-evaluation of the once-derided hybrid varieties, this is a discussion encompassing all you need to know in summary, but the author goes on to discuss in greater detail still the new varieties most commonly known to us as PIWIs (easier on the English-speaking tongue, at least until we get used to it, than the long form Pilzwilderstandsfähige). These are the new grape varieties bred for fungal resistance promoted by PIWI International (there are other organisations carrying out similar work such as ResDur in France).

Much of this work has been carried out by Valentin Blattner in Switzerland, which is where I first came across PIWIs, but you can already find a few on the shelves, such as Nu.vo.té from the Languedoc, made from Araban, and Metissage (both red and white), made by the Ducourt family in Bordeaux.

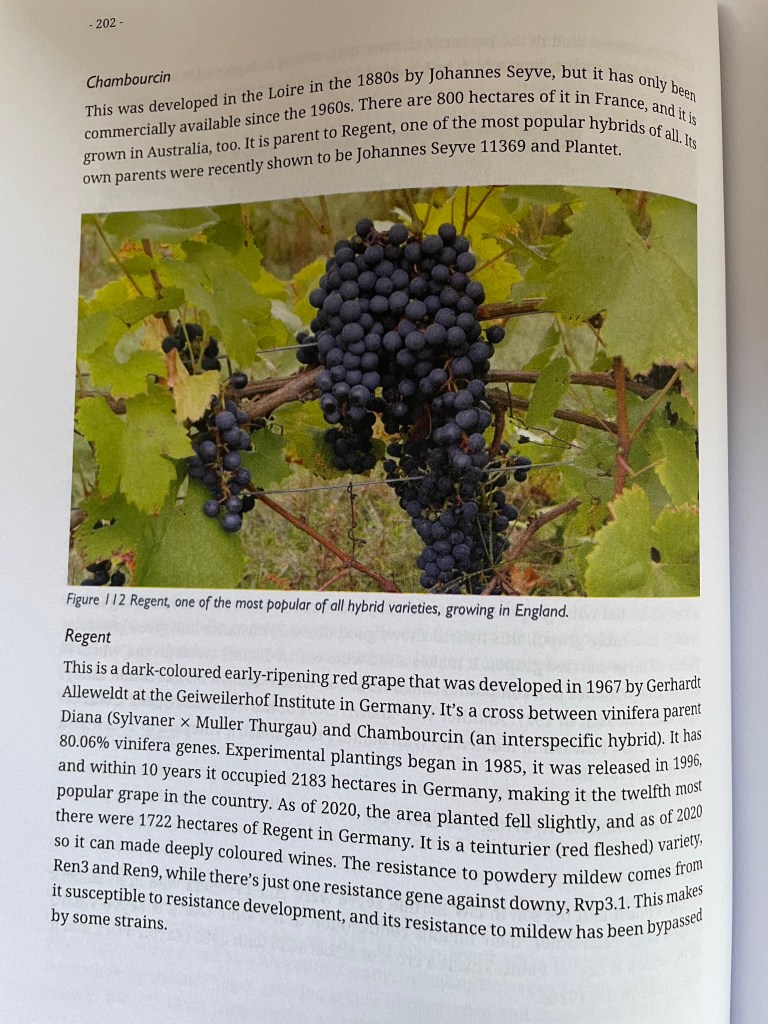

So, as well as seeing more hybrid varieties re-emerging in the wines we drink (especially in England with grapes like Regent, Rondo, Solaris and Seyval Blanc, and in Northeastern USA with Catawba and Concord, to name two), along with a few of Japan’s interesting Koshu wines being imported by adventurous wine merchants, new resistant PIWI grapes like Cabernet Blanc, Sauvignac and the Frontenacs are appearing too.

But I mustn’t get bogged down in this particular little obsession of mine when there are other exciting areas to explore. Not least epigenics, which, raising my hands, I knew nothing of before last week. It is an area of molecular biology which studies how plants can change how they grow in response to a changing environment. It’s a short chapter, but enlightening nevertheless.

One further key threat to vineyards the world over is trunk disease, especially but not exclusively Esca, though that has perhaps become the most topical. One of the most interesting parts of the whole book concerns the role of pruning in escalating trunk diseases, and we get to read (p291) the incredible story of the work of Marco Simonit (Jamie’s sub-title for this section is “making pruning sexy” and he’s not far wrong).

It’s a lovely self-contained tale of how someone with an ordinary (sic) background developed a passion which enabled him to see the wood from the trees and develop a whole new understanding of the vine’s structure and topography. Simonit is now one of wine’s most highly respected and consulted experts on pruning and vine health.

There’s also a section in this chapter on trunk surgery which is equally interesting, and I noticed an article on Wineanorak.com called ”Curetage: vine surgery for Esca in action, with François Dal”, which Jamie published a few days ago. Definitely worth a look for my most ardent readers.

Even more pertinent, perhaps, if you want to read a properly balanced discussion of the herbicide Glyphosate (aka Roundup), you will find one at p305 in the chapter on weed control and regenerative viticulture, where we move from the chemical products habitually used in greater and greater quantity over the past century in viticulture to other approaches from organics, biodynamics right up to permaculture. Jamie mentions the work of Masanobu Fukuoka, whose The One Straw Revolution (on “do nothing” agriculture) I reviewed myself (18/08/21). It’s a book which is both soulful and illuminating, and definitely Fukuoka was an inspiring, intuitive, individual.

If you think regenerative farming is something for the hippies, think again. I was aware, even though the time I would have been able to afford to drink their wines has long passed, that Château Lafite is seriously exploring regenerative farming, and there’s another interesting snippet in the book, Jamie talking to Manuela Brando who leads research at Lafite and the rest of the Baron de Rothschild properties. Even if Lafite is now well off my personal radar (I’m more of a “Le Puy” kinda guy these days), I cannot help but be very interested in what one of the wine world’s great icons is thinking about their future, and in Bordeaux no less, last bastion of chemical application in a damp climate..

A selection of the photos and diagrams which illustrate the text of the full edition

I’ll begin to wind up now, but I have really only scratched the surface of this quite remarkable book. Not least have I failed to mention the thirty-plus pages of case studies which prop up the end of The New Viticulture. In some ways it’s like a textbook, but in others it’s like a travelogue through viticulture over time, a story of trials and tribulations, then successes, but with fear for the future very much present. Within its pages you will meet some of viticulture’s potential saviours, scientists who have devoted a life to the vine and for whose work we should be extremely thankful. However, you will be equally aware of the risks of complacency.

Aside from the very real threats to wine as we know it from the corporate greed of “big wine”, which would very much like to transform wine as we know it over the next decade, and not in a good way, artisan producers of fine wine, interesting wine, and diverse wine, face very real threats from climate, pests and disease.

This book both attempts and succeeds, to analyse those threats and, through explaining the science of viticulture, points to a way forward. This is ultimately why “wine lovers” in the real sense will be impassioned by this book as well as gaining a great deal of scientific knowledge. I will not pretend that I have absorbed it on a single read, but that is as expected. I will go back and read individual chapters, trying to take on board their contents more fully. I hope, as a result, that even though I feel I know quite a lot about wine, my knowledge will be greatly deepened.

Any criticisms? Well, one-and-a-half. The half is typos. The New Viticulture is not littered with them, and almost all are simple omissions, a final square bracket here, a failure to use a plural form there, or a misspelling of a name which is elsewhere spelt correctly. There are just a few more typos than you’d get in a book published by a traditional publisher, because this work is printed and published by Amazon, presumably (forgive me if I’m wrong) in a “print on demand” basis. However, any typos are easily identifiable and don’t obscure the meaning of any sentence.

Another result of the publication choice is that the cover, both front and back, curls up. Either the card is a little too thin or it’s an issue with the binding. Again, it’s no big deal. For me both of those issues are acceptable if it means that the author actually makes some money from the book by having kept production costs down and hopefully getting a better return than with a book deal (I’ve no idea how the Amazon thing works). Think of the hours Goode must have put into creating this. I can see why he thinks it’s his best work. I do believe it stands as an essential contribution to our contemporary understanding of modern viticulture.

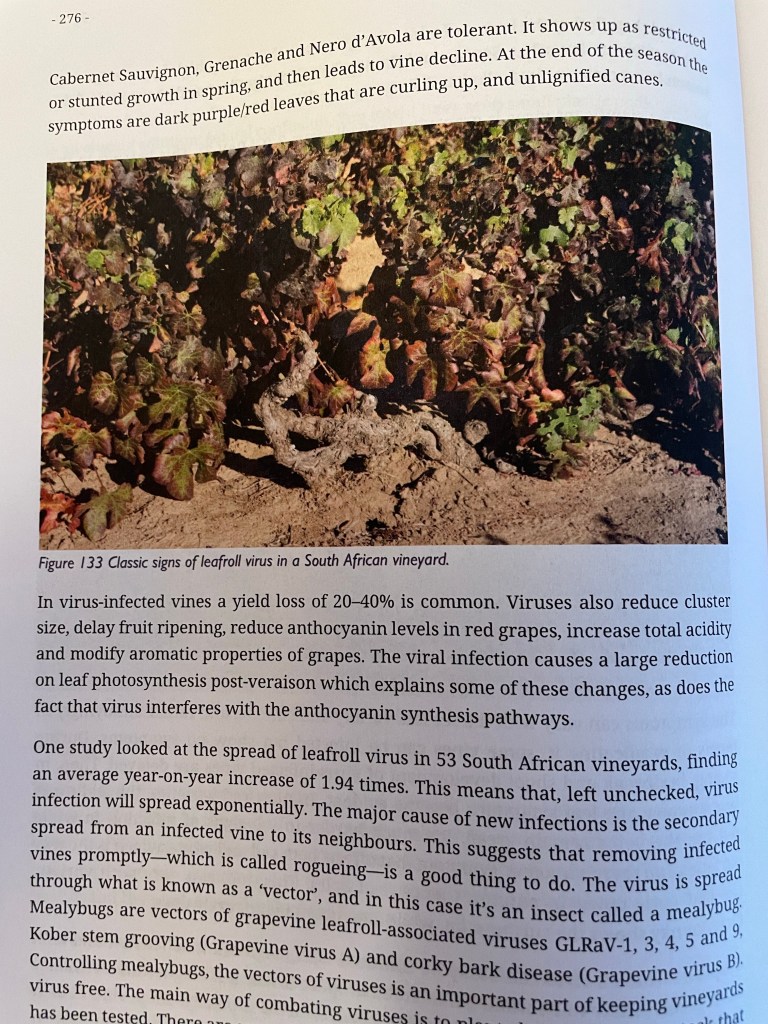

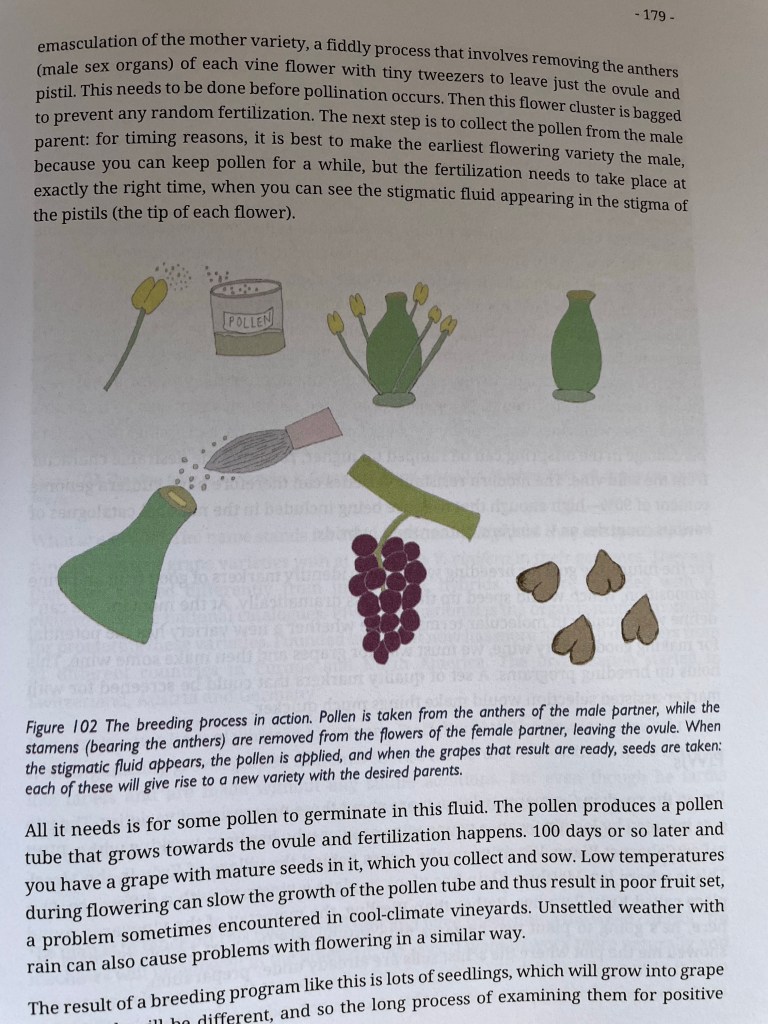

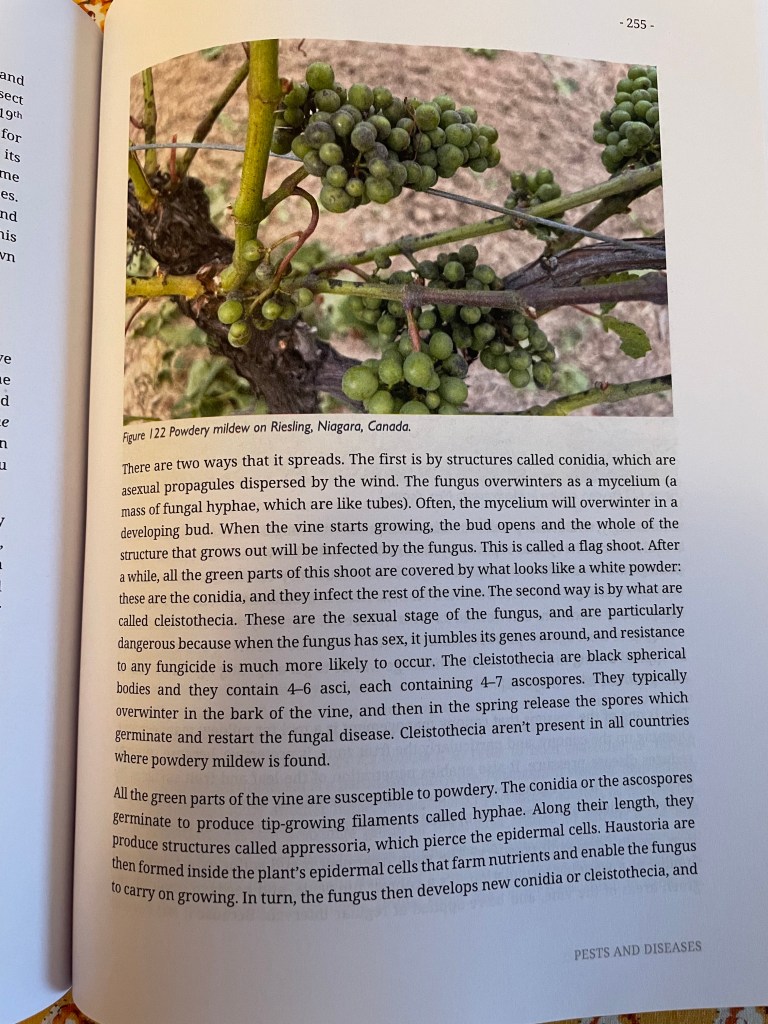

The New Viticulture is available from Amazon in all regions. It comes in two print options. The full edition, which includes photos, charts and diagrams, costs £34. A “student” edition is available for £18. The latter has the same text, albeit reformatted, without the graphics and photos. Personally, I’m pleased to have the illustrated version. The photos, or at least those which are not of relevant individuals, are very helpful in illustrating the text, whether that be of vine diseases, viruses, vine training, soil structures and so on. The drawn diagrams are no less instructive. However, I can see why some would want to save money, and this book will indeed be very helpful to students from Sommeliers to WSET to MW, where I would hope it might be essential reading. So that’s a “Buy”! Definitely.

Dr Goode, somewhere nice as usual

I opted for the Kindle version and it reads well on a tablet with all the photos and drawings.

There’s a lot of excellent work in here, including on my latest obsessions with pruning and vine care. Instructive but also very readable, there’s a lot of fascinating facts which were new to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So much new to me but also so much info on things I’m really interested in. Especially hybrids, PIWIs and pruning (for myself).

LikeLike

One of the women at vendanges this year is studying new ways of pruning and it was fascinating. It’s a process often just passed on to novices and yet plays a key role in the health of the vine.

You’re right there’s so much more in here but this is top of my agenda at present so good to read Jamie’s research and coverage as I respect his opinion a lot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Marco Simonit’s story is fascinating, and a nice story too (on pruning and vine topography).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I have read about him and watched some of his videos. Marceau Bardarias in France too.

LikeLiked by 1 person