Wimps is a wine lunch. It was one of the early examples of what people who inhabit internet forums call an offline, where people who meet online actually get together, flesh and blood. “Wimps” isn’t an acronym. It was coined by its founder, Keith Prothero, as a lunch for people who could only manage a bottle each at that time of the day (although, to be fair, the rule is ten bottles between each table of eight). It’s attendees all sign up through Tom Cannavan’s Wine Pages Forum, where most (but not all) of them spend at least some time talking about wine with fellow wine lovers. We bring the wine and the restaurant does the cooking, a (very) posh form of BYO.

For many years Wimps was hosted very generously by The Ledbury, but understandably after they got their second star it became very difficult to allow 32-or-so wine lovers to enjoy a cheap (for The Ledbury) fixed four-course lunch and bring their own bottles, when the place was full every day. So Nigel Platts-Martin (co-owner) generously moved us down to La Trompette in Chiswick a few years ago, and the institution that Wimps has become continues to thrive there, hosting lunches once a month, each on a different theme.

Some people go every month, almost religiously, whilst many others go perhaps once a year. There is usually at least one person there for whom it is their first time, but they are always made to feel very welcome. I hadn’t been to one myself for a long time when I attended the July Champagne and Chardonnay lunch last week. In the time I’d been absent the cooking at La Trompette had gone up another notch, and the wines were as wonderful as ever (not one dud on the day). The company was as good as ever too, a real mark of Wimps. My notes follow, but if you read through and fancy an outing at Wimps, click the link below to check out the August Lunch (each lunch is listed individually on the “Offline Planner” of the Wine-Pages Forum, and you need to register there to get onto the thread and sign up for a seat). It’s currently only £65 all in (no extras, not even a tip), a genuine bargain.

Wine Pages Offline Planner Wimps Link

At the time of writing, the link therein to future lunches appears to be broken. I’m sure it will get fixed.

WIMPS CHAMPAGNE & CHARDONNAY LUNCH, LA TROMPETTE, 28 JULY 2017

Wimps lunches always include extras like water, coffee, bread and an amuse-bouche or small starter with the first wine. We began with Truite et anguille fumée, radis noir, avocat and raifort, two pieces forming two perfect mouthfuls to go with NV Jacquesson Cuvée 736. These numbered cuvées are now well established for their quality/price ratio. The 736 was released in 2012, so this has been well cellared. It was based on the amazing 2008 vintage, bottled at just 1.5 g/l dosage. It’s delicious, fresh and with a nice line. Lemon citrus with biscuits and nuts supporting.

Langoustines rôties, beurre blanc au concombre, and verveine provided our main “starter” dish, delicately done with the cucumber adding a distinctive and cooling note. In many ways this was where the wine fireworks happened. 2000 Pol Roger Cuvée Sir Winston Churchill was more than a solid opener. This cuvée always has a certain style and stature, which even a vintage like 2000 can’t erase. It did have to battle the two (which then became three) Vilmarts, but was enjoyable in its own right.

2004 Vilmart Coeur de Cuvée was up against 2004 Vilmart Grand Cellier d’Or. You’d think this would be an unfair match, but the Crand Cellier d’Or is a beautiful wine when on song, and the 2004 is drinking now. It had nice development and was very much a “Vilmart”, but with a touch of restraint compared to the Coeur at this stage. A wine currently showing balance.

Initially the Coeur ’04 was bigger, with its wood ageing showing through more. It took time for it to show magnificence, but by the finish it had surpassed the baby brother. It still needs time, but it will make a very good Coeur. I said “three” Vilmarts. We were four tables for this lunch, and one of the others sent over a glass of the 2002 Coeur. I think I sadly drank my last bottle this year. At the time I got a sip it outdid both of the 2004s, perhaps not unexpectedly. Stunningly good!

Pain Perdu, ovoli cèpes et girolles and truffe noire was my dish of the day. Someone joked it’s really posh mushrooms on toast. I disagree. The fungi were top class and the truffle came through nicely. Someone said it was an Australian truffle. It was a bit more pungent that the Wiltshire truffle I had at Lime Wood (see recent article). I thought this dish impossible to improve.

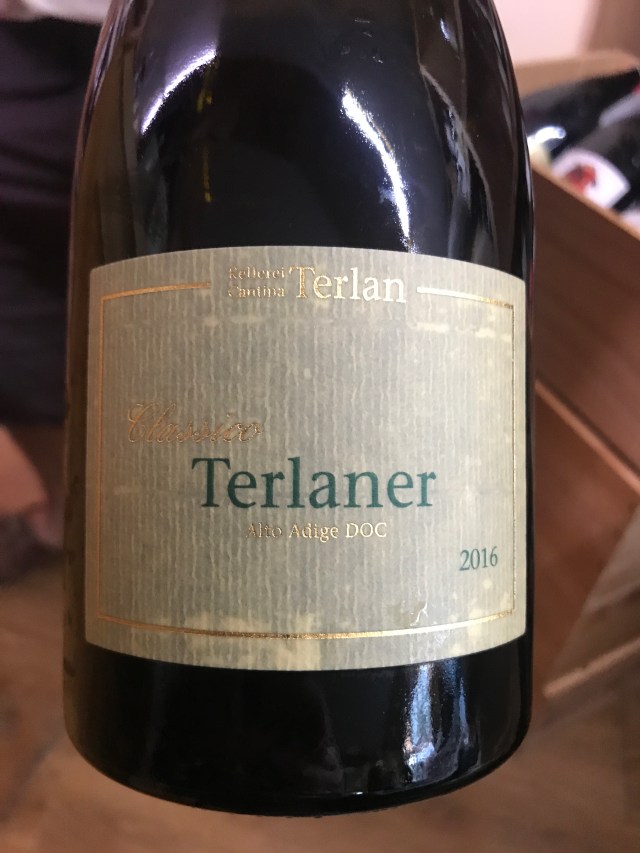

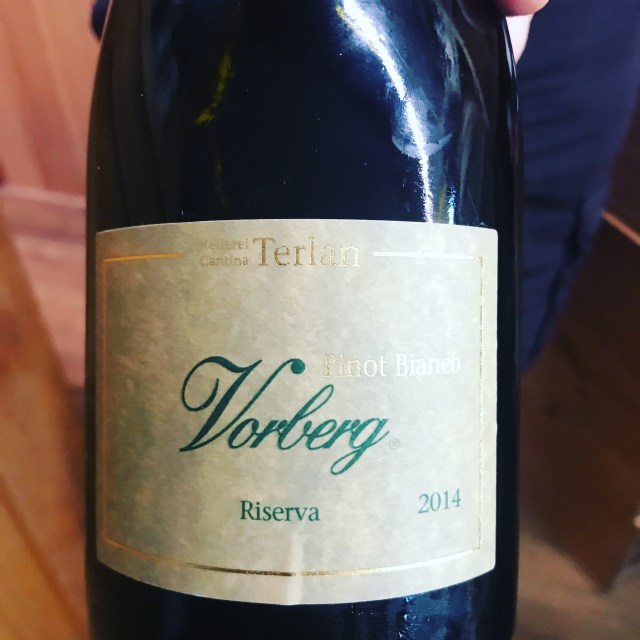

We were temporarily over to the still wines next, the Chardonnays. Three very different yet wonderful bottles. 2002 Chablis Grand Cru Vaudésir, Domaine Billaud-Simon comes from a producer I’ve enjoyed a lot in the past. There was certainly development and complexity, but also freshness beneath the mellow flavours. It is so unusual to find a honeyed note in Chablis but this had it. Superb!

Next we were treated to two very different Meursaults. 2010 Meursault “En La Barre”, François & Antoine Jobard was still quite structured with the nose developed a little more than the palate. Still youthful, though with the faintest note of butter, butterscotch even. 2012 Meursault Les Chevalières, Henri Germain was quite different, quite mineral for a Meursault, and leaner/lighter. Limey and fresh too. In fact, a good old fashioned White Burgundy in a way. My nostalgia for this, and my love of the Chablis made it difficult to decide which was wine of the flight, without any criticism of the Jobard. My mind changed several times on the day.

We were also passed a pour from a magnum of 1996 Meursault-Poruzots, François Jobard which was very good, but bigger all round. Just like I remember Meursault when I used to stay in the village. In a magnum it had kept very well, tasting a bit younger than twenty years old.

Carré de porc d’Iberique, navets, polenta et prune Reine-Claude was our final savoury course, with melting pork cut from the rack. And here we returned to Champagne with two late 1990s bottles. It’s rare for me to see a magnum of 1998 Palmer & Co Brut Millésime. It’s quite old fashioned, I suppose, dosed at around 11 g/l. Perhaps “traditional” is a better word, because I do not intend anything derogatory. Actually, the dosage doesn’t taste as much as 11 grams, perhaps the magnum effect, which also ensures a certain structure. A treat, even in supposedly more exalted company. Also, it was a match for the pig.

The Palmer was paired with 1999 La Grande Année, Bollinger. Now many of you will not have the highest regard for 1999 as a Champagne vintage. Others will know how successful this wine was in 1999. First, you notice the freshness, unusual for the vintage and, more recently, for this particular cuvée in general. It tastes considerably younger than, for example, 2000 does. Its energy makes it really enjoyable, but over time in the glass it develops complex flavours too. Delicious, with lasting impact which, good and enjoyable as the Palmer was, it could not match.

Now at this point I realise I’ve not got a photo of the Bolly. It’s hard to keep on top of things with all that food and wine washing around. But I have got a pic of a rare 1989 Trillennium Reserved Cuvée, Veuve Clicquot, which was utterly delicious for a wine that previous drinkers of this ’89 on the table had described as “tired” (not actually using such polite language – I’ve never had one, nor the similarly labelled 1988 and 1990 versions). What I don’t have though, is a formal tasting note for it. Oops! There was also a 1998 Nyetimber swishing around too, a wine from the first period at this English domaine, when it was fast establishing a name for Champagne-challenging quality. Another successful bottle, and proof that at its best, Nyetimber can certainly age.

Dessert was perfectly judged in both food and wine. A small piece of Tarte de nectarine, glace à la feuille de cassis et fruits was accompanied by 1983 Barsac 1er Grand Cru Classé, Château Climens. The nectarine tart had sweetness and a little acidity, but the contrast of the blackcurrant leaf in the ice cream made this among the best desserts I’ve had at La Trompette. Not over complicated, but subtle, it provided the right level of sugar rush to wake me up. The Barsac was lovely. Of course, 1983 was not especially fancied on release, but it happens to be the first vintage I bought, being on sale in the region the first time I drove down to Sauternes and Barsac (and wider Bordeaux). It wasn’t too sweet and it wasn’t too unctuous. Quite remarkable for its age, and for the vintage, I’d say, though I’m no expert on these sweet wines.

I thoroughly enjoyed being back at Wimps. Thanks go to the team at La Trompette, and to a kitchen which is cooking to a very high standard, more than worthy of its star. I can thoroughly recommend a trip to this part of Chiswick (although from Central London I’d say that Turnham Green on the District Line is probably the closest London Underground station at 10-15 minutes’ walk). A great lunch, great company, and wonderful generosity, as ever, with the wines.