I’ve been to the Red Squirrel Portfolio Tasting a few times now, and I can say with conviction that the 2018 event, at the China Exchange in Gerrard Street, Soho, on Tuesday this week, was the best ever. It was certainly the biggest in terms of the number of Red Squirrel wines on show (many of them poured by their maker), and I’m pretty sure in terms of the number of attendees too. Plenty of people are beginning to cotton on to the fact that Red Squirrel Wines has one of the most adventurous ranges in London. They are growing slowly but surely as well, and I think there were probably around 200 wines on taste this year.

I’ve not tried to cover them all, of course. There were producers I didn’t taste at all because, like Okanagan Crush Pad, I’ve already tasted and written about their wines more than once this year. Others with who I’m familiar only saw me taste one or two new or less well known wines. But at the same time there were some wonderful new wines to try, and my top three discoveries of the day are the first three producers below. There were so many fantastic wines, so read on.

AYUNTA, Etna, Sicily

Filippo Mangione struck me as a really nice bloke, and I’m not surprised that the folks at Red Squirrel have warmed to him. He’s in that mould of Martin Diwald, Arnold Holzer, or Christian Dal Zotto, people you’d happily go to the pub with. He has some of the oldest vines (some are 200 years old) on some of the oldest volcanic soils on Etna. The wines are made in one of the traditional, and the RS chaps tell me a very beautiful, old palmentos. Why did we not know about him?

Filippo showed three wines, to all of which I might be tempted to extend the handshake of excellence. Piante\Sparse 2016 is an Etna Bianco which is mostly Carricante, but ancient mixed planting means a number of stray varieties make it really a field blend (with around 30% made up of Cataratto, with some Inzolia, Zibibbo and Minella Bianca). They are all co-fermented. Nice and mineral, a bit of texture, very pure, and only 12.5% abv, so fresh as anything. Loved it.

Navigabile 2016 is an Etna Rosso red blend of mostly Nerello Mascalese with 20% Nerello Cappuccio and 10% others. It’s made in open top cement vats before ageing in 35 hectolitre wooden vats. It has that lifted perfume so characteristic of the Nerello varieties and smooth, ripe, tannins.

Caldara Sottana 2015 is a single vineyard contrada wine, 100% Nerello Mascalese selected from the oldest vines in the parcel. It has more spice than the previous wine with a peppery touch, and more concentration, darker and denser fruit. It needs time, I think, but impressive, and special.

The name? Filippo’s nickname, as “ayunta” is Sicilian slang, kind of “more”, which his grandmother used to say to get him to drink more milk. These are really lovely wines, and my discovery of the day.

MÔRELIG, Swartland, South Africa

Andrew Wightman makes natural wines with as little intervention as possible at the base of the Paarderberg Mountain in Swartland (Western Cape). The family bought the farm in 2011 but 2015 was their first vintage. Vines, some planted back in 1965, are on excellent decomposed granite. All wines mentioned are 2017.

The range begins with a very tasty A&B’s Blend which is about 70% Chenin Blanc, 30% Clairette. Chenin Blanc is nice and clean, made in old oak and impressed, but then came the Old Bush Vines Chenin. This is from vines aged 53 years or over, off some of the farm’s best granite terroir. It’s just a step up from the previous wine in terms of the complexity of the basket-pressed old vine fruit, but it also has greater presence, a nicely rounded out wine. There’s a touch of apple freshness coupled with a touch of quince. My favourite of Andrew’s wines.

That’s not to say the reds aren’t good. To steal a tasting term from Jamie Goode, the Syrah is just so smashable. Semi carbonic, ten days on skins in old oak, used both for fermentation and maturation, 13% abv. There’s genuine polish to the palish fruit on bouquet and palate, fresh and with a touch of elegance. Nice!? More than nice!

The Hedge is the flagship red, a blend of 75% Syrah with 13% Carignan and 12% Cinsaut (the SA spelling is used here). The Syrah gets a 30 day extraction and is then blended with the other varieties, which add freshness. A lovely, and potentially quite complex, blend.

LOWERLAND, Prieska, South Africa

Well, I’d never heard of Prieska before. It’s a new Wine of Origin in the Orange River region, in an agricultural district known only for bulk wine, if at all. The idea that someone is doing interesting stuff here would, I’m told, cause a bit of mirth among some South Africans. By the way, you pronounce it “loverland”.

The organic grapes are grown on a mixed farm by Bertie Coetzee, a former rock musician with some impressive winemaker mates (JD Pretorius, Lukas van Loggerenberg and Johnnie Calitz), to whom he trucks down batches for them to make the wines. The key here is altitude. Ripening is difficult enough without a good lot of summer rain to make things harder, but the wines below somehow show quite amazing freshness and complexity.

Lowerland MCC 2016 is a delicious, fresh, Colombard sparkler (14 months on lees, zero dosage), which already shows more presence than most Colombard from Gascony. Witgat 2017 is Viognier, but not at all in the fat and oily style, despite nine months in old oak. It reminds me of a Haisma, or of Stéphane Ogier’s white “Rosine”, in its freshness, definitely worth trying if you think you (or your guests, in which case serve it blind) don’t like Viognier.

With Vaalkameel 2017 we are back with Colombard. Whereas the “MCC” was made by JD Pretorius, this one was made by Lukas van Loggerenberg. The name means “pale camel”. No idea! Great stone fruit character dominates, so much more personality than you usually get out of Colombard, but it’s different to the MCC. Seeing 12 months in barrel, this is a ringer for a top Chenin, and Nik said it had been called out as Chenin when tasted blind on many occasions.

JD, Lukas and Johnnie all came together to create Die Verlore Bokooi 2016, a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Petit Verdot (both 35%) with 25% Syrah and 5% Merlot. On the face of it, it’s a quaffer, quite easy going, but it does have a touch of structure and wow, it grows in the glass. This was a “Hidden Gem” in the 2018 Platter’s Wine Guide, and I agree with them, it’s a brilliant find. Actually my favourite wine from Lowerland, though others run it close (especially that pale camel).

The final red, Tolbos 2016, is unusually 100% Tannat. This is a really imposing flagship wine with a meaty, iron-rich, bouquet from only 13.5% of restrained alcohol. Nik said Lukas is planning a trip to Madiran, so much does he love Tannat. I sincerely hope he’s not disappointed, because I doubt he’ll find too many Madirans as attractive as this approachable star.

DAL ZOTTO, Victoria, Australia

This is an old King Valley family who originally emigrated from Italy, and we know that King Valley has some great Italian grape varieties planted as a result of those migrations. Christian is one of the great characters of the Red Squirrel herd, and does a brilliant job of promoting the wines his brother makes around the world.

Dal Zotto is a perennial favourite of any tasting where their wines are on show. The grape focus is purely Italian, with delicious varietals from King Valley grown Arneis, Garganega, Sangiovese and Barbera, all great value. In addition, Dal Zotto makes a real Italian speciality which, given the appalling status of the Italian original among some wine lovers in the UK, really should be tried. If you like tasty but uncomplicated Italian fizz but can’t bring yourself to buy Prosecco (good versions as there surely are), then look no further than the wines tasted below.

Pink Pucino NV is a fun fizzy rosé, dry and zippy but not thin, and pretty fruity. Pucino Col Fondo 2016 is just like a colfondo Prosecco in almost every respect, except again, Aussie fruit shines through in a lovely lifted bouquet. Love the bitter, saline finish.

Christian also poured a new, unlabelled sparkler, a petnat. Some fruit was pressed at 22 baume and added back to the base wine. It’s also “Col Fondo” (“with the bottom”, ie all the yeast cells etc, making it cloudy with all that tasty sediment – shake it up or stand it up, the choice is yours). It has no name yet, so look out for a new Dal Zotto addition. It’s a cracker.

VINTERLOPER, South Australia

Vinterloper started out as an urban winery project but has since grown into one of the new stars of the Adelaide Hills. The wide range includes the innovative “Park” range, sold in 50cl beer bottles which are just right for…er…taking to the park.

There are still a couple of wines under the Urban Winery Project label. White #3 (2017) blends just over half Pinot Gris with Gewurztraminer and a little Riesling, making an interesting dry but aromatic wine. The 37% Gewurz comes through on the nose, and it has a touch of exoticism, but it’s also a nice reviving wine.

Urban Winery Project Red #6 (2017) is a rich Syrah/Tempranillo blend, fairly simple on the face of it, but there’s a nice bitterish cherry touch on the fruit and a savoury note at the end.

I will admit I’m a sucker for the Vinterloper Lagrein, named If Life Gives You…2017. It’s a new wine, just for the UK market. I hope that’s because we are sophisticated enough for this juicy Northeast Italian variety. It’s not an especially sophisticated wine, but one you can really enjoy, with a good amount of character and personality.

ESCHENHOF HOLZER, Wagram, Austria

Arnold Holzer’s wines have featured in my racks for years and I can recommend all of them, especially if you are looking for cheap wines to splash around because he puts a lot of care into these. Invader Orange 2017 is one of the most interesting inexpensive wines around. It’s a Müller-Thurgau skin contact wine. It smells like an orange wine, but it actually comes over really clean on the palate, and the fruit is very evident. It’s one of a tranche of wines redefining this much maligned variety.

The Orange 2015, by contrast, is serious stuff. For a few years this has been up there with my favourite orange wines. It helps that the grape is Roter Veltliner, a rare but lovely Austrian variety. The colour here is true orange, unlike the paler Invader. The skin contact character really hits you on first sniff, even before you allow the extract and texture to coat your tongue. It’s majestic, just so long as you appreciate the “white made as a red” style and philosophy…which I do.

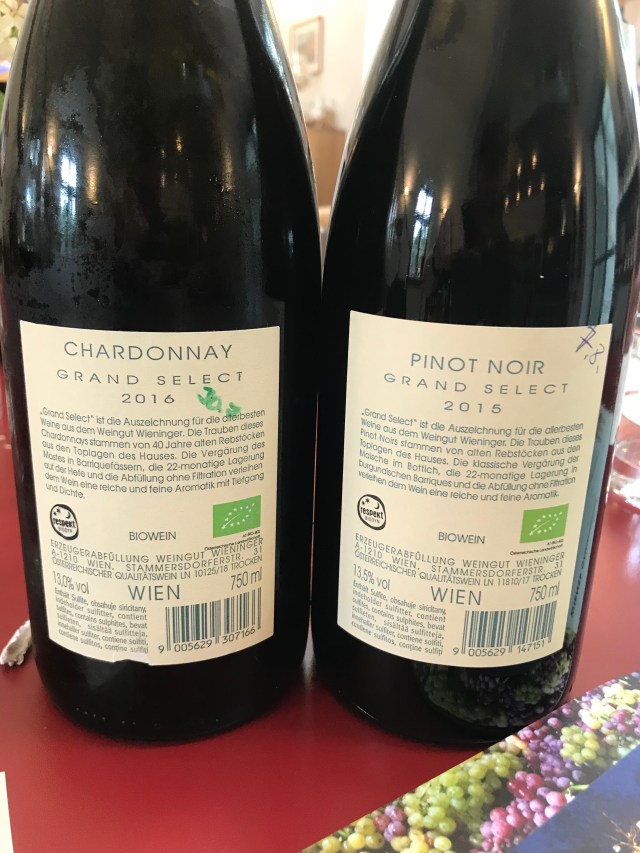

BIOWEINGUT DIWALD, Wagram, Austria

You probably know by now that Martin Diwald is a neighbour and old school mate of Arnold Holzer. The Diwald family have been organic since the 1980s, among the country’s first. Both estates are at Grossriedenthal, in Wagram, more famous, for now, for Napoleon’s famous victory than for wine, perhaps. The region stretches for around 30km along the Danube, east of Kamptal, Kremstal and the Wachau, and not too far from Vienna.

I’ve known Martin Diwald’s wines for exactly as long as I’ve known Arnold Holzer’s, and his Grüner Veltliner Sekt has been a firm fixture of previous summers. As I’m always drinking his whites I think I’ll take the chance to plug the only red Martin had on show, Grossriedenthal Löss 2016. It’s Zweigelt, a variety which can be hard drinking when people extract too much from it, and there are horrible commercial versions of the grape variety as well. When it is done right, it can be both juicy and fresh without being too simple. I know some Austrian producers who don’t like Zweigelt, but Martin does. Maybe the pair of us are perverse. I doubt it.

BLACK CHALK, Hampshire, England

Black Chalk is a new English sparkling wine producer. I was really impressed with their wines when I tasted them for the first time at the London Wine Fair, and after a few extra months in bottle on cork they are even more delicious now.

The winery is based near to Winchester, and although no vines are owned, all the bought in fruit comes from a ten mile radius of the winery, purchased from growers with whom Jacob Leadley (as winemaker for the very successful Hattingley Valley Wines, one of England’s best kept secrets until recently) has close relationships. The name “Black Chalk” comes from the use of the medium in art for sketching out ideas before committing them to canvas.

There are two Black Chalk wines right now, both from the 2015 vintage, and with a production of around 10,000 bottles per year, no major growth is planned (although somewhat bigger harvests will help increase production a little).

Black Chalk Classic 2015 is a blend of half Chardonnay with decreasing proportions of Pinot Meunier and Pinot Noir. With 9 g/l dosage, it is elegant and fruity at the same time. The Meunier gives lovely fresh acidity in a relatively warm vintage. Ageing is in wood, with one new 225 litre barrel, lightly toasted, adding a touch of complexity.

Wild Rose 2015 is a very pale pink where the Meunier makes up just less than half of the blend with 34% Chardonnay and 25% Pinot Noir. Raspberry and strawberry fruits precede a clean and crisp finish. Lovely. These are very user friendly wines, no ultra low dosage or anything. I think Jacob has judged them beautifully, and this is a label to watch.

CHAMPAGNE LEVASSEUR, Marne Valley, France

David Levasseur has around four hectares at Cuchery and at Châtillon on the Marne, planted mostly by his grandfather in the 1940s. You don’t often read about this small 35,000 bottle-a-year producer but the wines are very impressive. There are two wines named after the road where the family lives, Rue du Sorbier. They are both Meunier dominated (80%) non-vintage wines, one a Brut which is fruity, and one a Brut Nature (zero dosage), which is dry and more savoury, a food wine.

Extrait Gourmand Rosé is down to 50% Meunier, with 30% Chardonnay and 20% PN. Its colour is somewhere between deep salmon pink and bronze and there’s a bit of extract. “Gourmand” gives away the intention…drink it with food, either firm fish, good seafood, or white meat etc.

There are two wines labelled Terroir, also NV. The Blanc de Blancs (100% Chardonnay) has a powerful nose with a touch of salinity. The Blanc de Noirs (all Pinot Noir) has a biscuit nose and is fuller on the palate, with a touch of spice. These are quite singular wines, both with a tiny production of around 1,500 bottles each vintage. Both wines are showing amazing length. They feature the old fashioned method of tying the cork on with string, very labour intensive and as much care is taken in making these wines.

I tasted a nice wine from the Loire, from Muscadet in fact, that I remember tasting a couple of years ago. It’s that “sparkling Muscadet”, but of course Les Perles de Folie from Frederic Guilbaud is not labelled as such, merely as a “Vin Mousseux NV”. Made from the region’s Melon variety, it is tight and focussed with almost rapier-like acidity and a very fine spine, delicious.

Bruno Bouche is a grower from Limoux I don’t recall coming across before, but Être à L’Ouest 2017 is a cheeky Chardonnay with just 12.5% alcohol and, relatively speaking, is cheap as chips. With a great fun label it should fly off any wine list where the wine drinking public are not too up themselves.

Clos Cibonne is one of my few Provençal favourites and these wines are as good as ever. All the wines to a greater or lesser degree feature the autochthonous variety, Tibouren, and I do love the wine where this grape variety is placed in the forefront. Tradition Rosé Cru Classé 2016 is often called just “Tibouren”, although it does contain 10% Grenache here. The 2014 drunk from magnum in August was a reminder that, like the pink from Château Simone, this ages superbly, and improves with time.

KEWIN DESCOMBES, Beaujolais, France

Kéké is one of a bunch of relatively new stars in Beaujolais who are taking the wines back to their roots as well made but gluggable crowd pleasers in the best sense. I really like the 2017 edition of Cuvée Kéké, which has delicious, light, lifted, cherry fruit.

Gluggable doesn’t mean just simple. Kewin makes some lovely wines from, and labelled as, Morgon, and his Morgon Vieilles Vignes is a touch more serious. I prefer the 2016 over the 2015. The nose is more restrained, the fruit more balanced. There is grip here too, and it needs a little time. It has restraint to accompany the density of old vine fruit.

EMIL BAUER & SOHNE, Pfalz, Germany

This domaine is special for several reasons, although the wine names and labels can have the effect of taking the focus away from the serious work Alexander and Martin Bauer have been doing since they took over from their father in 2011. I mean, forget concrete eggs, these guys make one wine in carved stone “barriques” (Riesling Granit, not on taste here).

The 2017 version of Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll (Riesling) is, like many of the dry Rieslings I’ve tasted from this vintage, zippy with fresh acidity, but being The Pfalz, there’s fruit coming through too.

I want to highlight the Scheurebe, Scheu Aber Geil 2017, which has a different kind of fruit, green and bright, with a touch of grapefruit. I’ve not seen it before so it may be new to Red Squirrel, but it’s tasty and interesting. Do you really want me to translate? “Shy but horny”. I really can’t say about the last bit, but I’d not call it shy!

If You Are A…2017 (see label below) is like a New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc, but a good one. Clean gooseberry fruit with more tropical notes which don’t dominate. Fresh acids but not tart, nor under-ripe.

Always Enjoy Life 2016 is a Pinot Noir pink, very pale after just a short period on skins. Tasty, but maybe not as interesting as the whites (to me). What is of interest is the red. German Merlot! My Merlot Is Not The Answer 2016 is unusual, not merely for what it is, but also for the fact that despite 14% alcohol, it seems lighter and more restrained (well, a little) than many Saint-Emilions. But it is very juicy and packed with fruit, plus a little grippiness, which will soften with a little age if you want it to.

BRUNA, Liguria, Italy

I often mention these wines, from a producer I only come across at Red Squirrel Tastings. I suppose I’ve always had a soft spot for “good” Ligurian wines, especially Pigato (the Ligurian strain of Vermentino). Of the three “Vermentino” wines Bruna makes, the slightly more expensive Pigato Le Russeghine wins out in 2017. Very unlike the old style of acidic Pigato, this has a whole lot going on, richer and more complex, but it’s still a fresh white at the same time.

Bansigu Rosso 2016 is one for those who enjoy oddities. It’s a blend of Granaccia (70%), with Rossese di Campochiesa, Barbera and Cinsault, plus others, with 13.5% alcohol, and a slightly animal nose (I mean that in a good way). There’s fruit there, and tannin. Just something a little different, but taste it before you buy a case. I know not everyone is as nuts (I mean adventurous, of course) as I am.

I’ll mention here another wine from one of Red Squirrel’s Ligurian producers, Altavia Rossese di Dolceacqua Superiore Riserva 2012. This is the local grape of (mainly) Western Liguria. It is pale with cherry fruit and bite. It’s another wine which initially seems less alcoholic than its 13.5% on the label. Unusual, but less so than Bruna’s red (though I have to say guys, come on, the label!).

AZORES WINE COMPANY, Azores, Mid-Atlantic

The Azores are a third of the way to America, although the islands, of which the volcanic cone of Pico is the main one, belong to Portugal. You can read about how António Maçanita has brought about a renaissance in Azores winemaking in my article here. The story is one worth reading and maybe I’m in a minority, but it really made me want to go out and see these remarkable vineyards (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) for myself.

António is out there making wine right now, but he was ably supported on Tuesday. I couldn’t resist trying three wines here, despite having tasted them a good few times in 2018 already. Terrantez do Pico 2016 (not 2015 as listed, and not the same Terrantez as in Madeira) is a lovely mineral wine, only marred by its price (probably around £50, justified by the tiny 1,000 bottle production and the cost of producing wines in general 900 miles off the coast of Portugal).

Tinto Vûlcanico 2016 is a much cheaper introduction to the AWC range. It’s a field blend of a whole load of grapes almost no-one has heard of, but with some Touriga, Merlot, Syrah and Aragonez (aka Tempranillo). There’s a bit more of this (3,330 bottles in 2016). The lifted, iron filings, nose is really characteristic of volcanic-grown red wines, so I think the terroir shines through in a really attractive way here, which I know has pleased most (perhaps all the people) who have tried it in my presence. You get an added bonus with this wine – the label pinpoints the Azores on a map for those who may be floundering.

I wanted to re-taste Isabella a Proibida 2016 because the keen-eyed reader will recall that in my last article I mentioned a wine I tried made from the vitis labrusca Isabella variety when in Austria in August. Interestingly, Isabella, as a Native American species, is supposed to be illegal for wine making in the EU (in the article I link to above you can read about the threat faced by António from the authorities when he initially believed this wine was from Isabella, cough), yet the Austrian wine, Weinhof Zieger’s Uhudler frizzante, appears to be quite open about the variety, at least according to Austrian friends who buy it (and Wikipedia).

This Azores wine is a little strange and a lot interesting. It has fruit, simple but rounded out mainly strawberry fruit, but salinity too, from the terroir. It makes the wine slightly sweet (but not really) and sour. But you don’t get any more than a hint of the “foxy” stuff going on in the Uhudler. Perhaps the terroir is such a strong influence…or maybe the variety really isn’t quite Isabella. That would let António off the hook, at least…

PASAELI, Izmir, Turkey

You have to hand it to these guys, and owner Seyit Karagözoglu. They are making some truly tasty wines in an environment (I’m talking political, not climatic) that is not encouraging for winemakers. Where Turkey once looked to Western economic models, and indeed proved a massive success story, wine does not fit in with the stance of the current government. Advertising is almost impossible, so try the wines, and thank Red Squirrel for importing them.

The wines are made from a range of varieties, from the lowly Sultana table grape for which Turkey is famous, through varietal Sidalan, Yapincak, Çalkarasi (vinified as a rosé) and a couple of reds. 6N 2016 is 80% Karasakiz with 20% Merlot, a smooth and fruity wine, quite easy going, and inexpensive. The range tops out with international varieties blended together (both Cabernets, Merlot and Petit Verdot). This K2 2014 is dark and brooding and, even with a few years in bottle, is quite big. But impressive. They do deserve our support.

CROSBY & LOCKHART CELLARS, California, USA

These are Red Squirrel’s first US wines. Their story is a little unusual as they come from a New York distributor which went into winemaking twenty years ago in order to provide an inexpensive but well made line for their own customers. The fruit is sourced from all over California and the wines are made by Anna Davis in Healdsburg, Sonoma County.

These are all simple wines, but well made. There’s a Crosby Chardonnay, and four Lockhart-labelled wines – Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. These are clearly aimed at the on-trade, I assume, but should do well. They provide up front fruit, none of the sweetness which masks almost everything else in the big Cali-brands, and so should go with food in a restaurant setting. None are over alcoholic (the Cabernet, for instance, is an almost light and restrained 13.5%). I think a few restaurant buyers could get quite excited having these on the list. Decent labels help.

Native New Yorker in full flow…kinda wish I’d had longer

I can’t expect any more of you than to read all of this (over 4,000 words), which only makes it a trifle annoying there are so many other producers I haven’t mentioned. If you come across wines from Valdonica (Tuscany), Bellwether (Coonawarra) and Okanagan Crush Pad/Haywire Range (British Columbia, Canada) and you’ve not read what I have said about them before, do dive in. I don’t think any of their wines are less than very good indeed. Personally, I’m a big fan of the Crush Pad.

Thanks Nik, Great Tasting! A man who enjoys his work!