Here in the UK a series of proposals has just been published under the ambitious heading of a “National Food Strategy”. Its author, Henry Dimbleby, has outlined a raft of measures we need to adopt in order to save lives from our poor diet, to protect nature and the environment and ensure that farming in the UK is sustainable. Perhaps the most eye-catching proposal is that we should reduce meat consumption by 30%. Less eye-catching, but no less important, is the need to massively reduce agri-chemical inputs. Aside from the dangers to human health they may or may not pose, long-term, it is their destruction of ecosystems which has finally been recognised (in some quarters) as unacceptable.

Such proposals may well get nowhere, and especially those relating to synthetic chemical interventions. Aside from the fear that climate change will bring new challenges, no challenge to the profits of the large agri-chemical producers will go unchallenged. Whilst low input agriculture remains a minority sport, there’s little to worry about, but we can’t have the whole world going organic, surely? Think of food security, think of the costs (they say).

In many ways the food strategy is framed in a way that puts the focus on a change in diet, and on educating people to change habits. In other words, a market-led approach. What needs to happen (as indeed with things like plastic packaging) is a producer-led approach. We are starting to see this to a degree, but nowhere near enough.

I think we can say that in some respects the wine fraternity is moving ahead of other agricultural sectors, and one way it is doing this is by exploring the methods of regenerative agriculture. No-till farming is not new. In fact, such methods were common in many countries until the 20th Century. I keep hearing about projects in the UK, and I even read about a return to this way of farming in The Guardian newspaper this week, in Spanish olive groves. But the methods, practical teachings and philosophy of the man I will introduce you to have taken off all over the wine world, whether directly influenced or indirectly.

Those who know producers like Ligas (Greece), Lissner (Alsace) and Meinklang (Burgenland), to name but three, are all following principles which effectively leave the whole ecosystem to regulate itself. In the case of vines there is no intervention between rows and just a little shoot repositioning (no annual pruning). Such ecosystems seem to become self-regulating after a while. I was recently with Tim Phillips (Charlie Herring Wines) in his Hampshire vineyard and we were discussing our passion for this very book as he showed me the cuttings to be returned to the earth as natural fertiliser.

The book is The One Straw Revolution and the author is, of course, Masanobu Fukuoka. I think those interested in natural wine and low intervention wine production will enjoy reading it, not least because of the increasing interest in Fukuoka from the wine community. Perhaps the time has arrived to shift our focus away from the biodynamics of Steiner and Thun, just a little, and to focus on how wine in general might benefit from a “no-till” regenerative approach.

Fukuoka was born in 1913 and lived a long and eventually contented life, passing away in 2008. Trained as a scientist (plant pathology), he broadly managed to avoid combat in WW2 working as a produce inspector and researcher in Yokohama. This gave him an insight into Japanese agriculture, which underwent great change after the war, largely as a result of American influence, both in terms of what to grow (Japan was a big potential market for American cereals) and how to farm.

In rejecting modern agricultural methods, returning to farm on the island of Shikoku, he developed a philosophy which some called “do nothing” farming. He applied his methods to both the dual cultivation of rice (summer) and grain (winter) in the same fields, and to his citrus orchards, in which he also planted his vegetables, amongst the trees. Some thought him crazy, but his methods worked. He matched the best yields in his neighbourhood without the costs associated with mechanised, chemical, farming, and with far fewer hours work than his contemporaries.

Fukuoka’s farm became the focus of attention, both from other scientists and from people looking for identity in a new way of life, the latter forming a community in huts on his mountainside.

The key to Fukuoka’s philosophy and methodology lies in the ability of nature to carry on doing what it does without much help from humans. In fact, Fukuoka’s light bulb moment may have been when he saw an abandoned field full of weeds, but with an ample crop of rice growing up among them.

A natural ecosystem includes a fluctuating number of predators which generally appear to balance each other. Too many of one type of insect and you get more predating spiders, too many spiders and there’s more food for the birds. Even common rice diseases righted themselves. In fact, as for yields, his shorter and healthier plants produced the same number of rice grains as the taller chemical-fed fields. What’s more, his natural food began to get a reputation which could have enabled him to charge much higher prices (as the retailers did who bought it), except that he believed such food should be available to all (an issue in our market, for sure).

The application of agri-chemicals on a large scale is largely a 20th Century phenomenon. In the 1960s activists drew attention to the potential harm to humans some of them could cause, especially Rachel Carson in the USA. Yet although her warnings were heeded to a degree, once DDT was banned the pressure kind of fell away.

Fukuoka outlines four principles to “Natural Farming”:

1 No cultivation (ie no ploughing or tilling);

2 No chemical fertilizers or prepared compost;

3. No weeding (weeds build soil fertility and balance the biological community); and

4. No other chemicals.

Soil health is absolutely key. This is a mantra we hear almost daily now, but not from a majority of farmers. And indeed viticulteurs. This despite so many photos of napalmed vineyards. Now, chemical applications by heavy tractor seem the easy route, and no one thinks of the long term.

It reminds me of a story in the James Rebanks book (see further reading below) English Pastoral. An old farmer was mildly made fun of for having been left behind by the agricultural revolution, for being a bit “backward” in taking up any new technologies. After he died a soil analysis was undertaken. On intensively farmed land this is essential because the soil is slowly dying and needs constant “replenishment”. On Henry’s farm they discovered the soil was rich and healthy, full of worms, very fertile. Henry had added no chemicals to his land and had not spent thousands of pounds doing it.

Quoting Rebanks “The men had discussed it in the pub. Dad said the way farming was going was insane. That old Henry had known more than the rest of us daft fuckers put together”.

Masanobu Fukuoka recounts a visit from a university professor who finally understood why there was no leaf-hopper problem in these fields…because natural predators of the insects were there in abundance. It dawned on him that in the other fields all the predators had been eradicated by spray treatments, yet here a natural balance in nature was maintained. “He acknowledged that if my method were generally adopted, the problem of crop devastation by leaf-hoppers could be solved. He then got into his car and returned to Kochi”. Even when his methods were proved to work, no one dare advocate them on a large scale.

Of course, many grape growers are highly focused on soil health these days. I only choose to mention the Rennersistas in Gols (Burgenland) as an example because soil health featured very early on in my conversations with Stefanie Renner, even before I visited them. One aspect of soil health Stefanie believes has a profound effect is a cover crop. As well as putting nutrients back into the soil they compete with the vines and help in some way to concentrate grape flavour. As Stefanie said in a recent interview with Littlewine (littlewine.com), “the wine tastes different with a cover crop”.

This ties in very well with Fukuoka, because he advocates a cover crop as an essential part of his regenerative agriculture. Along with a straw mulch, he uses white clover, which he found in his particular circumstances when used together control but not eliminate weeds, which play their own part in soil fertility and in a regenerative ecosystem.

This small book is a delight to read, well translated (by Larry Korn, Chris Pearce and Tsune Kurosawa), it’s a mere 184 pages long, made up of very short chapters. They set out the reasons Masanobu left science for the farming life, his practical methods and especially later in the book, his wider philosophy.

The Preface is written by Wendell Berry. Best known as a writer, and as an anti-Vietnam War activist, he’s also a farmer and has written widely on this subject, becoming an influencer here as well. The Preface is useful in putting methodologies specific to Japan into a wider context. As the American Berry says, Fukuoka’s techniques will not be “directly applicable to most American farms” but they do provide a great example of what can be done. Berry introduces the founder of organics, Sir Albert Howard, and highlights some similarities in their beliefs.

He also highlights a key element to Fukuoka’s thinking, asking the question “what will happen if I don’t do this?”. In this respect you could say Fukuoka is “a scientist who is suspicious of science”, but in reality, he is merely questioning the instructions of those who possess “piecemeal knowledge by specialization”, as a child might question the instruction of a parent. Why? What for? Because it is clear that the specialist does not see the whole picture, just as the scientist does not see how nature performs without his or her intervention.

In one of Fukuoka’s later, wholly philosophical, chapters (Drifting Clouds and the Illusion of Science) the author is expansive in his criticism of aspects of science, or at least the ways in which specialised, segmented, science dominates our lives. In a way such science has helped form our current economic conundrum, and it is the same conundrum for agriculture (and by that we include viticulture) as for climate change. We are locked into the capitalist requirement for growth and progress to generate increasing profit.

It is such thinking which creates our current crisis whereby all of the things we need to change seem unchangeable. As Chomsky points out, our problems are systemic because the way we do things (mechanisation, fossil fuels, agri-chemicals etc) are locked into a profit-driven system, and that system cannot easily be changed. But change must come and only consumers and farmers can effect these changes when related to agriculture. The pressure from the multi-nationals and financial institutions (investment banks solely responsible to their shareholders) is against them, but slowly change can be made. It has to be.

Masanobu Fukuoka described a so-called “do nothing” method of agriculture successful on a tiny scale on one of the islands of the Japanese archipelago. He suggests that great change can begin with one straw of barley. It is exactly the kind of revolution we need…in thinking about food production as part of our desire to feed the word, healthily.

In Fukuoka’s own words (page 3) “This method completely contradicts modern agricultural techniques. It throws scientific knowledge and traditional farming know-how right out the window. With this kind of farming, which uses no machines, no prepared fertilizer and no chemicals, it is possible to attain a harvest equal to or greater than that of the average Japanese farm. The proof is ripening right before your eyes”.

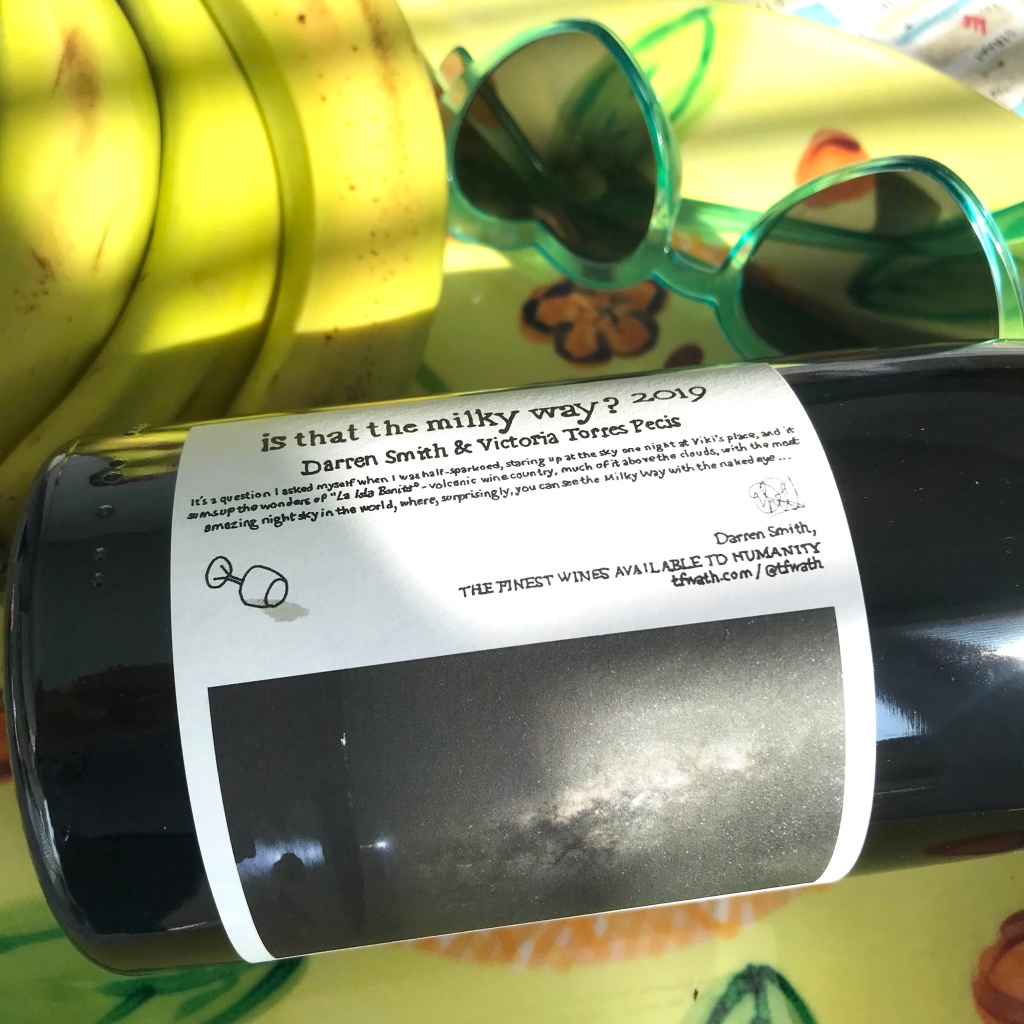

Such results may or may not have a wide application in agriculture in general (and I know we have not discussed various climate events which have produced famine in the past and will do so in the future), yet those who are trying elements of this form of regenerative agriculture have achieved quite a degree of success. It is clear that those in viticulture who have taken on board Fukuoka’s teachings appear to be forging ahead, and if you look at the producers I’ve mentioned in this article, who are just a sample, the proof is in the bottle.

If you have the slightest interest in growing food, and especially if you are interested, as I am, in experiments at the cutting edge, pushing the boundaries, of wine production, I promise that you will find this both practical and philosophical book a great little read. A tenner well spent.

The One Straw Revolution by Masanobu Fukuoka was published by the New York Review of Books(this edn 2009, soft cover/paperback), originally published in Japan as “Shizen Noho Wara Ippon No Kakumei” (1978) by Shunju-sha (Tokyo). It may be available on a number of the larger online sources, including Blackwells, Amazon etc.

There are at least a dozen books I could recommend as very peripheral reading, and I imagine at least half my readers will have read all of them. However, the following four books are lovely reads and throw light on different aspects of agricultural knowledge and practice. I know I’ve mentioned these before, but sometimes it doesn’t hurt to labour a point.

English Pastoral by James Rebanks (who previously published “A Shepherd’s Life”) (Allen Lane, a Penguin imprint, 2020) – a shepherd who is so much more than that.

Wilding by Isabella Tree (Picador, 2018) – England’s great rewilding project which I visit frequently.

Dark Emu by Bruce Pascoe (Magabala Books, 2014) – Australia’s indigenous peoples were not hunter-gatherers.

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer (Milkweed 2013, Penguin 2020) – As Pascoe (above) describes the understanding of Australia’s land, including its aptitude for producing food, by its original inhabitants, pre-colonisation, so this author shows the unique understanding of North America’s capacity to produce food by its own indigenous peoples. Both highlight the way that science, perhaps with the arrogance of a colonial mentality, has ignored deep knowledge learnt from nature over centuries.