Tutto Wines held their French Portfolio Tasting at Ducksoup in Dean Street, Soho, yesterday (hence the linguistic mangling). Many of you will already have read my article which covered the (mainly) Italian side of their list, which they showed at the Vaults Tasting in Farringdon last week. As befits a small but adventurous importer, the French side of the list is pretty tiny, only seven producers on show, but it is very well formed. They also happen to work with a couple of producers whose wines I have loved for a few years, but who are hard enough to find in France, let alone in the UK. Their availability in London seems almost a miracle.

LA GRAPPERIE – Coteaux du Loir

You probably don’t need telling that the River Loir is a northern tributary of the Loire itself. The wines up there are not especially well known, but it does provide a young winemaker with an opportunity to grab some land for less than a small fortune. Reynaud Guettier, based in Bueil en Touraine, has done just that, around 4-5 hectares in numerous plots of old vines (most around 40 to 80 years old). He began work in 2004, but Tutto have just been working with him for a couple of vintages. The wines are all Vins de France and, like all the wines on show yesterday, no sulphur is added.

La Bueilloise 2013 is a pét-nat made from an even split between Chenin Blanc and Pineau d’Aunis. The latter is a terroir sensitive variety found mainly in Anjou and Touraine, which often produces palish, peppery, reds (and pinks) which can be surprisingly tannic if not handled well. It’s sometimes known locally as Chenin Noir. The grapes for La Bueilloise are direct pressed, so the colour is in the dark yellow to orange spectrum. It’s quite cloudy, though that may be the latter part of the bottle with its yeast sediment. It’s also very fresh and dry, quite precise and direct. Nicely savoury on the finish too. It comes off a mixture of red clay, limestone and some silex, and you get the impression that the terroir comes through the winemaking, not always common with the pét-nat genre.

Aphrodite 2010 is old vine Chenin (some vines are 100 years old), undergoing a direct gravity press into old barrels, lees ageing without stirring, for three years. Nice complexity from this six year old with its soft and gentle nose.

La Désirée 2011 is a Chenin selection with a five year élèvage in old oak. The nose is more varietally Chenin than the Aphrodite. It’s a bigger wine, perhaps less fresh but this is down to more body and complexity. Quite an imposing wine, in a positive way. Impressive.

Le Gravot 2011 is a blend of 75% Pineau d’Aunis with Gamay, Grolleau and Côt (aka Malbec), whole bunch fermented before a year’s ageing. It has nice fruit complementing a lovely pale red colour, but there is that characteristic tannic bite and peppery finish, so I definitely recommend it as a food wine. It could alternatively take being served cool.

JEAN-PIERRE ROBINOT – Jasnières

Robinot is pretty well known to lovers of Loire natural wines. He’s knocking on, in his sixties, but this unassuming man, described by some as a Loire Legend, has his wines served in some of the smartest and hippest bars and restaurants in Europe and beyond. He’s also a prominent member of the small SAINS group (Sans Aucun Intrant ni Sulfites Ajoutés), which is a strong signal as to what you are getting here. Jean-Pierre is also famous for his first career – he ran the well known bar, Ange Vin, in Paris before returning to the place of his birth, Chahaignes, to begin a new career as a winemaker in 2001. In fifteen years he has achieved miracles, but not without pretty much alienating the region’s wine authorities, who perhaps find the wines a little atypical, but more importantly, too intellectually challenging, at a guess.

L’As des Années Folles 2014 is Robinot’s beautiful pétillant-naturel, a blend of Chenin and Pineau d’Aunis, the latter adding a touch of colour after 15 months on lees. Frothy, fresh and clear, this is perhaps Robinot’s simplest wine, but boy is it good. Very clean as well, on nose and palate.

Bistrologie is the one I know best from this range. The 2013 is 30-y-o Chenin Blanc given a one year élèvage. The orange hue is not from skin contact, but from late picking with possibly a hint of botrytis. I like this wine a lot, very “drinkable”, if you know what I mean.

Charme 2013 gives you 20 year older vines and a longer ageing for a few more pounds. The main difference to me is in the nose, a higher tone and greater precision and concentration.

Le Regard 2014 has a nice “iron filings” nose with maybe a hint of violets or lavender. It’s 100% Pineau d’Aunis aged in fibreglass vats (must admit, the nose got me thinking concrete, it has a nice earthy element beneath the smooth fruit).

The last wine from Jean-Pierre is Nocturne 2014, his most expensive wine (this, and Le Regard, are both also available in magnum). It is made from very old Pineau d’Aunis (80-110-y-o) vines and this time aged in old wood, not fibreglass. Colour isn’t really deeper than Le Regard, but the nose is much more concentrated, quite lovely in fact. There’s also more tannin so it does seem to need ageing, but it has the whiff of potential about it. A very impressive bottling.

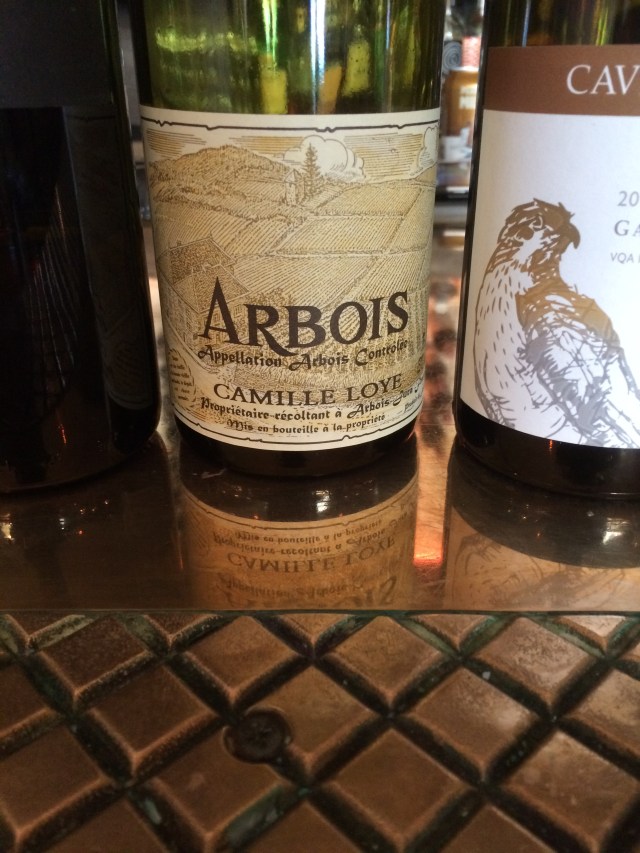

DOMAINE DE L’OCTAVIN – Arbois

Regular readers who go back a long way with me will know that I’ve visited Alice and Charles’ Arbois domaine, and love their wines. I’ve purchased them on all my recent visits to the region, but apart from a brief spell with another UK importer, they have been off our UK shelves for a while. Sad, because their wines are just so exciting and interesting. But they are also pretty scary for the traditionalists. They’ve had a hard time of it since starting out in 2005- originally calling themselves Opus Vinum, but hey, guess what, the folks at California’s Opus One didn’t like that and threatened all manner of nastiness through the corporation’s lawyers, so the story goes. It saddens me most because Alice Bouvot (I’ve only met Charles briefly) is such an amazingly nice, kind, person, as well as a talented and extremely hard working winemaker. Every other producer I know in Arbois always has nice things to say about them.

They renamed themselves as Domaine L’Octavin, retaining a link to their passion, Opera, and have built a range which seems to grow every year. They have been inspired and aided by Stéphane Tissot, and in fact they do seem to have plots of vines in locations quite close to some of his (and I’m sure the bubbling amphora in their winery has something to do with Stéphane – I think it came from Frank Cornelissen). Such is the demand for these wines that two of their five on the Tutto List had sold out in bottle before the tasting, but there is still a little of the Corvées Trousseau in magnum. The remaining three wines are available, but will probably sell out quickly.

Pamina 2014 is a Chardonnay from Le Mailloche, the site for possibly my favourite of Stéphane Tissot’s single vineyard bottlings. One reader I know will be interested in the fact that the vines used to be farmed by Domaine Villet, one of the very first organic domaines in the region. It has 18 months in old wood and is a very unusual Chardonnay, really taking you to a different territory. How you react will probably determine whether you are wary of this domaine or filled with enthusiasm. Personally, I’m in the latter camp, as you can see. An exciting wine, which in a quiet and understated way almost redefines the grape variety.

Ulm comes in both 2014 and 2015 vintages. 2014 is 85% Pinot Noir blended with 15% Chardonnay, whole bunch fermented for three months. Very appealing nose, dry, it has a chalky finish but smooth fruit as well. 2015 has a different blend, 55% Pinot Noir with 45% Chardonnay. That makes for a pale, light red so that you might think it’s a Poulsard. It is clearly quite youthful and has a little tannin, but there’s a really nice mouthfeel. It’s a very tasty wine in both vintages, but the 2015 blend somehow appeals more, although it’s slightly less approachable.

I found a bottle in the cellar with no vintage, possibly a 2013 from before the days when you could stick a year on a Vin de France. Must drink it soon. I have also drunk several other Octavin wines recently, mentioned somewhere in the “recent wines” posts on the Blog. One of them, the Dora Bella Poulsard, is one of the wines sold out by Tutto. Both that and the Trousseau, which they still have in magnums, are at least as good as those tasted here. Also look out for Cherubin, a Vin Jaune except that all L’Octavin wines are made outside the appellation system, and “Cul Rond…“, a blanc de noirs Poulsard, vinified as a white. Smells of Poulsard, has the texture of a Poulsard, but is white, so a nice visual challenge. Oh yes! Perhaps Tutto will get some in the future. I know Alice was working on a blend of Jura and Savoie grapes, a bit like Ganevat with his Jura/Beaujolais project. This couple never stand still.

FREDERIC COSSARD – Saint-Romain

Frédéric Cossard makes wines under the Domaine de Chassorney label, and also operates as a micro-negoce, and I tasted a mix of the two yesterday. The USP chez-Cossard is a very long fermentation, with no cooling of the must, and when I say “long”, I mean at least 40 days, sometimes months. The wines undergo no burgundian batonnage, and are not racked, but attention to detail enables the fruit to be kept pristine. Frédéric makes a raft of wines, and Tutto were showing six.

Bourgogne Blanc Bigotes 2013 is, like its red cousin, a negoce bottling but it still comes from 40-year-old vines, near Puligny. Simple but savoury, and very fresh. These wines are not cheap, at this level of the AOP, but they are very good, as good as many domaine Bourgognes.

Combe Bazin 2014 is a village Saint-Romain, from a reasonably large lieu-dit up in the hills (on limestone, south of the village, above Sous le Château). The nose begins quite linear but the palate is nicely rounded yet fresh, not heavy. I do like this, a good leap from the Bourgogne (in quality, not price). It may be climate change, but have we not seen a real quality jump in both Saint-Romain and Saint-Aubin in the last few years? Of course, 2014 is generally excellent for Burgundy whites (not shabby for reds either, of course), so this is a relative bargain.

Bourgogne Rouge Bedeau 2013 is from three different vineyards near to Volnay, the fruit macerated for one month in open topped conical vats. Pale, fruity nose and smooth on the palate.

Saint-Romain Sous Roche 2014 is made from more old vine fruit from a site further north and next to Combe Bazin. This, however, is a rouge, and even this young, there are cherries and berries matched with intense (and cf my previous article, I’m going to use this word without shame) minerality.

Volnay 1er Cru 2013 is a blend of Frédéric’s two Premier Cru sites which suffered from hail in 2013, not surprisingly as Volnay copped it badly. Slightly hard and closed nose to start with but the nose develops in the glass. It needs a little time. The fruit is nice here, it’s just still grippy. A good effort in the circumstances, showing that attention to detail in a tough year will yield results. Not sure how much of this he made, but there can’t be a lot.

Nuits-Saint-Georges Les Damodes 2013 is, along with the two Bourgognes, a negociant wine, although I think the domaine may own some Nuits vines in the Clos des Argillières Premier Cru. It comes from a split site on the border with Vosne. South of the vineyard road is Premier Cru and north of it is the Village AOC. Presumably, as this is not labelled 1er Cru, it’s from the northern section. It’s another precise wine but bigger than the Volnay, and with more evident structure. It’s hard to read – it certainly has the fruit to age and I think it is going to be more impressive than the Volnay in time, for sure. Not quite as pretty, though.

DOMAINE SAUVETERRE – Macon

These wines are very much worth a look. To say they are good value perhaps does them a disservice, given their provenance in a region increasingly being noted for quality as well as well-priced wines. Jérôme Guichard bought his few hectares of vines from Guy Blanchard. Never heard of him? Well, his wines were served at the opening of Racines in Paris for starters.

Jérôme has a mix of about 1.5ha each of Chardonnay (the original parcel), plus Gamay planted on black volcanic soils in the 1940s, just after WW2. The Chardonnay, Vin d’Montbled 2014 is quite unusual, with a spectrum on the nose quite unlike what you’d expect of Chardonnay. Blanchard’s Chardonnays were said to smell like Savagnin (as a compliment), but this is something different. The wine on the palate is really vivant and fresh.

The Gamay is called Jus de Chaussette and I tasted the 2014 again. It is fermented long and slow as whole bunches. The nose is pure Gamay but, along with the cherry fruit on the tongue, there is a spiciness you don’t expect from this variety. Fascinating in a good way. Both of these are wines to try, the Gamay being remarkably cheap for such an artisan wine with a real point of difference.

JULIE BALAGNY – Fleurie

What can I say about Julie Balagny? I adore her wines, more than any other of the newer producers who are setting Beaujolais alight (and there are a good few). But her wines are harder to find than hens’ teeth, and I’m caught between a rock and a hard place. I’m sitting here typing this when I should have put in my order, and you lot are going to beat me to it. Not only that, my usual Parisian sources are, almost as we speak, being scoured by certain individuals and when I go in a couple of weeks, they will be cleaned out (my friends tell me they are even thinner on the ground there than a year ago).

Thankfully Julie doesn’t suffer fools, and I know people who’ve tried rocking up at her place and been given short shrift, so that method of procurement is probably not recommended. If these are all gone I may cry. But be warned. It’s not Bojo as we know it, Jim. Leave your expectations at the door…and wonder just how the Tutto boys managed to land a pallet (if probably a very small one)? The one advantage I have, I think, is that people who don’t know the wines might look at the prices and find them high for Beaujolais. You won’t find them cheaper anywhere else…in fact, I think you won’t find them hardly anywhere else.

Simone is the one with the punky lady on the label, although you can’t always go by labels here, which are prone to change. It is usually a Fleurie, but in 2014 the fermentation either got blocked or wouldn’t finish. So Simone in 2014 is a Vin de France, quite easy going, just 12.5% alcohol, and quite frankly, delicious.

Beaujolais 2015 is Julie’s straight cuvée from a parcel she only acquired last year. It’s a carbonic maceration wine, I think technically “Villages”, but the vines (near Fleurie but outside the Cru, not in the south of the region) are around 80 years old. Cherries and more cherries, a touch of high toned fruit, but its rounded mouthfeel makes this classic glugging.

Moulin-à-Vent “Mamouth” 2015 is made from some of Balagny’s oldest vines, over 100 years, planted on a steep, quartz-rich, slope. The nose is deep and serious, and so is the wine itself. Serious stuff, and seriously good, but very distinctive. This may actually be the finest cuvée I’ve tasted as yet from 2015, and I’ve had quite a number. But remember, I’m biased and this can’t possibly be seen as an objective statement!

Julie Balagny

VINYER DE LA RUCA – Banyuls

Manuel Di Vecchi Staraz doesn’t sound very French, and in fact he comes from Tuscany. I admit, I knew nothing about him until yesterday. He makes what looks like a red pét-nat with a name remarkably similar to Lambrusco, a wild looking Mourvèdre in a litre bottle, and a pink wine in a tetra-pak p0uch, called Judas.

On show at the tasting were two wines. Ellittico 2015 is a Grenache/Carignan blend (bottled as Vin de France, not a Collioure table wine) , foot trodden, 2-3 week maceration, old oak. Delicious! Plummy with perhaps a hint of violets.

Even better, but frustratingly bottled in a 40cl “vase” (albeit a very lovely one, just not much in the bottle) is Manuel’s Banyuls 2012. 16% alcohol, smooth, concentrated, long…the nose is stunning, kind of caramel/toffee with red plums with a bit of butter too. Every sniff is different as it evolves in the glass. It’s smooth, not at all spirity (Manuel distills his own spirit for fortification from Grenache), and has a lightness to go with the concentration. It’s hard to judge a wine like this on a mere “sip and spit”, you really need a contemplative glass, of which 40cl won’t provide many (maybe just enough to share, but preferably for solo consumption). But admitting that, it does seem exceptional, and a little different to the more classically produced Banyuls I’ve drunk. This is a barrel-aged version, no demijohns or carboys.

For a nice touch, Alex of Tutto pulled a bottle from under the counter before a few of us left the tasting. It was made from one of those myriad but delicious Piemontese grape varieties which are now seeing a wider appreciation outside the region, Pelaverga. It’s not (I think) one of the wines they currently list from Olek Bondonio. Olek makes wine in Barbaresco and quite a few people commented positively (some extremely positively) on his Barbaresco Roncagliette 2013 at the Vaults Tasting last week. Pelaverga 2015 comes from the same site as the Barbaresco. It’s a simple, quirky, wine with predominantly red fruits (strawberry, mainly) but a touch of bramble in the texture on the finish. If you like your Freisa, Grignolino (Olek also makes one of these) or Ruché, then this is one to try.

Tutto Wines are:

Alex Whyte – alex@tuttowines.com ; Damiano Fiamma – damiano@tuttowines.com

http://www.tuttowines.com

For prices and availability contact Tutto.