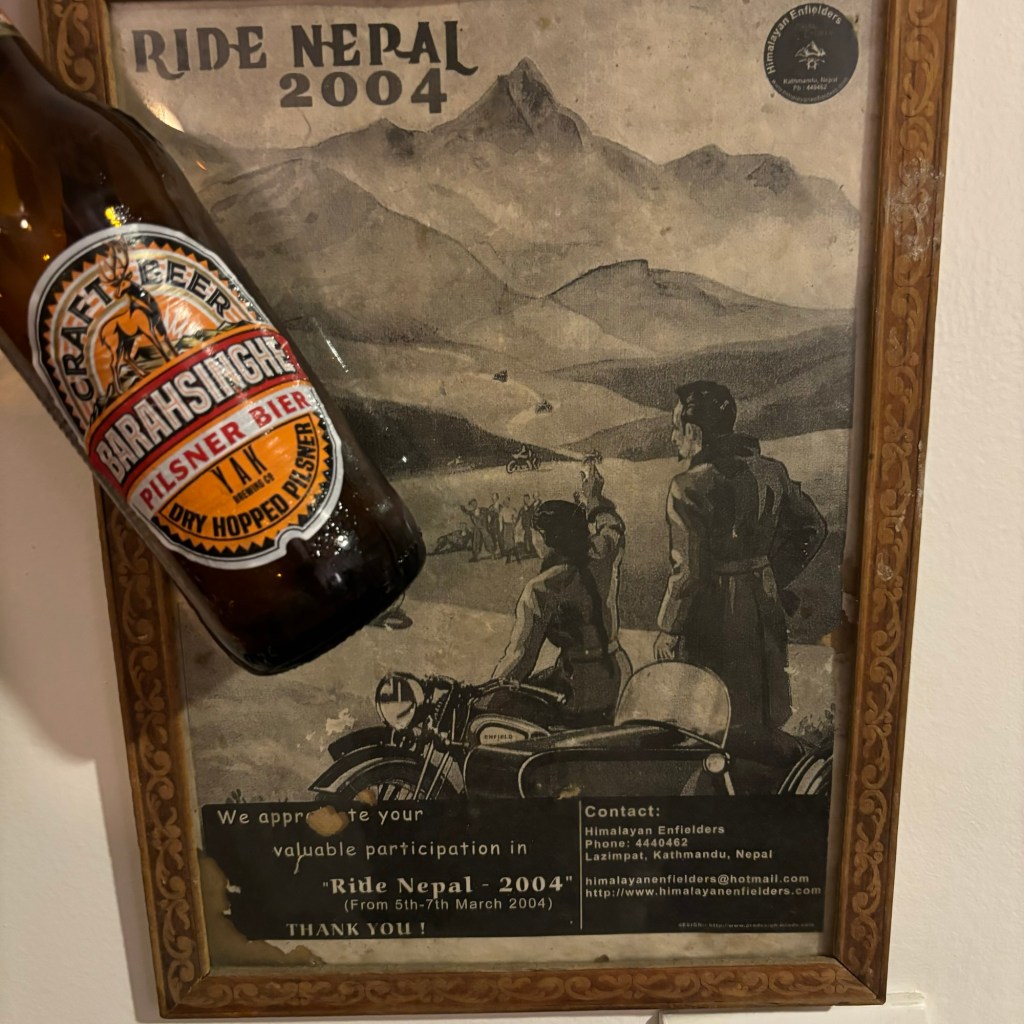

November’s Recent Wines are once again cut short, in this case by our trip to Nepal, taking twenty days of “home drinking” out of the equation, but we did manage to consume six bottles in the ten days we had left in the month. Unsurprisingly we kick off with a bottle from Nepal, before an amazing Czech Sauvignon Blanc, a white wine no less good from Colio, a Pfalz (but only just) Spätburgunder, an orange wine from Hungary and, to draw November to a close, a luxurious Pinot Gris from one of my very favourite winemakers in Alsace.

It is certainly looking like there will be considerably more wines consumed in December, considering what has been opened here so far. As a result, I can’t promise to keep up my wholly unintentional recent habit, as mirrored above, of all the wines being from different countries, but at least among these half-dozen bottles there are no duplicates in that respect.

White Ashish 2020, Pataleban Vineyard Winery (Chisapani, Nepal)

I managed to get hold of three different Pataleban wines in Nepal but didn’t visit the winery this time. The road, and there is only one road, that heads west from Kathmandu to Pokhara is the main transport route to and from India. The road is clogged with traffic close to Kathmandu at the best of times, and last visit we were stuck in traffic for so long that to get back to the Pataleban Resort Hotel they sent a couple of scooters to rescue us. After the recent floods have washed away parts of this road, causing even more chaos, we didn’t risk using it, which also curtailed our plans for a weekend at Sarangkot, above Pokhara.

Pataleban, Nepal’s only producer of “grape wine”, is near Chisapani, 16km west of the capital. They now have three main vineyards at Kaule, Kewalpur and Khani Kola, totalling around 40 acres on the slopes of the Kathmandu Valley, rising to 3,000 masl at their highest extreme. The project began with a small vineyard around the Pataleban Resort Hotel, planted mainly to hybrids with initial assistance from Japan (Nichibi Kaikan Winery) in 2006.

I notice that World of Fine Wine recently ran an article about wine from Bhutan, seeming to imply, incorrectly, that wine in the Himalayas is something new. If, as that article suggests, wine from Bhutan, like Hugh Johnson’s famous definition (for that very journal) of fine wine, is “wine worth talking about”, then come on folks, let’s talk about wine from Nepal!

More recently, technical help for Pataleban has come from Switzerland and Germany, and plantings in the main sites further west along the valley have been predominantly European viniferas. The winemaker’s son, Siddharta Karki, is currently completing various stages in Germany, and will no doubt return with even more knowledge to assist his father, Kumar Karki’s, already heroic efforts (and trust me, making wine in Nepal is heroic on several levels).

There are currently three wines commercialised (though I have seen a photo only of the mythical “Muscat Blue”), and this white wine, as far as I can ascertain, was made from 40% Chardonnay, 40% Gewurztraminer and 20% Heida in the 2020 vintage. It is fruity, off-dry and reminds me a little of a richer Jurançon with bottle age. Or perhaps that Bergerac Moelleux I drank a few months back, though it is certainly not “moelleux” in the sense that any Loire drinker will recognise. It’s more “off-dry”.

It has scents of quince and yellow stone fruit with a touch of melon. I might say that considering where it came from, it’s an amazing wine because it stands up on its own as a decent bottle whatever its origin. The climate can be a struggle, especially the monsoon rains which usually (pre-climate chaos) end in October. Rain and humidity before and around harvest can be more challenging than heat at other times of the ripening cycle.

I will admit that I did have some concerns over the vintage. Wine stores in Kathmandu don’t tend to go heavy on the aircon and summers are hot, but this bottle might have been a recent arrival from the winery’s cool storage, because equally the capital’s stores are not going to hold very large stocks.

This cost between £8-10 in Kathmandu. As far as I know the wines are not exported to Europe, but I have seen it listed on a couple of US web sites at around $10. That’s cheap so the information may be outdated. Good luck in trying to get some and don’t hesitate to let me know if you do.

Sauvignon Blanc 2022, Mira Nestarcová (Moravia, Czechia)

Mira works alongside her husband, Milán Netarec, but harvesting from her own vineyards at Velké Bilovice and Moravsky Zickov, in Southern Moravia, vines which are minimally pruned and so produce very tiny berries. Viticulture is organic with some elements of biodynamics incorporated, and a strong focus on regenerative agriculture. In all respect, like Milán, Mira’s wines are made with minimal intervention, naturally, from vines sitting on loess, clay and sandy soils.

Winemaking uses a mix of wood and concrete. The wine, I have to say, is exceptional. I bought a selection of all of the cuvées that the importer brought in and perhaps in some respects the Sauvignon Blanc was the one I was least excited by before I opened the bottle. I was so wrong. For starters, the wine is quite unique for the grape variety. It’s not “Loire”, certainly not “New Zealand”. It perhaps slightly resembles a Styrian Sauvignon Blanc, which is a compliment in itself.

The fruit is concentrated and intense but the acids which are present, and certainly characteristic of the variety, are wholly balanced by the wonderful, pure, pear and gooseberry fruit. Alcohol is just 11%, yet the wine is in no way “thin”. There’s a great mouthfeel which presumably comes from a little skin maceration, though there are no tannins (not something I’d want from SB anyway). There’s definitely some complexity developing. I’m sure this will age a little, but if (no, when) I buy another bottle, I doubt it will last long in the cellar.

This was circa £30 direct from Basket Press Wines. I shall have much more to say about Mira in the future, no doubt.

“K” 2021, Edi Kéber (Collio, Italy)

It’s a tough life when you drink two white wines this good consecutively. Edi Kéber has vines in an amphitheatre at Zegla, within the region of Collio-Goriziano (to give this sub-region its full name) in Northeast Italy. The Kéber vines, close to the border with Slovenia, are farmed without chemical treatments, and the traditional element of the winemaking centres on autochthonous varieties vinified in concrete vats and old casks. I believe he is now making only white wine.

This is a blend, traditional for the region, of Friulano with Malvasia and Ribolla Giala. Friulano, formerly called Tocai, or Tocai Friulano, goes by the rather odd name of “Tai” in the Veneto. I can see why, but don’t like it. The variety is in fact what those with a good knowledge of French viticulture will know as Sauvignonasse (sometimes Sauvignon Vert). In France it is a variety of little note, but you might recall it has also been widely planted in Chile, of all places, where it was mistaken for Sauvignon Blanc. In wider Friuli it can excel like nowhere else.

As is common in the region, the grapes in this blend have seen long skin contact, and it was bottled without fining, nor filtration. It is bone dry, mineral and grassy. It has texture, and fruit, and the palate has an awful lot going on, but the spine of acidity keeps it well in focus. The length is excellent. It is both pristine yet mouthfilling.

Looking back on my notes, I’m not sure they actually convey as much as I’d have liked, but I know it was exceptionally good. Perhaps it’s a wine that is slightly enigmatic? My bottle came from The Solent Cellar (£30). The importer appears to be Third Floor Wines in Manchester, but I’ve also seen it at Shrine to the Vine.

Spätburgunder “B” 2013, Friedrich Becker (Pfalz, Germany)

Another lovely wine from Friedrich, or “Kleine Fritz” as he’s known locally. He’s one of several high-quality producers in the village of Schweigen, right on the southern border between Pfalz (Germany) and Alsace (France). I don’t think it an insult to those other growers, one of whose wines I also much admire (Jülg), to say that Fritz has gained the most praise of all of them from those who truly know German Spätburgunder/Pinot Noir.

The slopes of Schweigen fall quite precipitously towards the Alsace town of Wissembourg, almost ending at the walls of its beautiful eleventh century abbey complex, whose monks planted these slopes. Some of the vines farmed by the Schweigen winzers are actually across the border in France, indeed these are the village’s best sites.

The wines are legally produced under the German wine laws, but a convention has arisen where the vineyard names, which would be Grand Cru in Alsace but whose names are not permitted on the “German” wines, are denoted by their first letter (as is common elsewhere, but for different reasons). It’s a little similar to Collio, the location of the previous wine, where winemakers often have vines over the border in Slovenia.

The terroir here on the slopes is limestone and marl. This particular wine was aged seventeen months in Burgundian casks, 20% new. When Fritz began getting a lot of critical acclaim he was making his red wines very much with Burgundy in mind, perhaps especially the silky Pinots of Musigny. However, latterly he has become more determined to produce wines which express the Schweigen terroirs, and personally I think that is the right way to go.

This wine had quite a bit of extraction and so twenty years plus ageing has not been a problem. It still has grip, a little tannin and texture. The fruit is lovely floating cherry on the nose, echoed on the palate, but here we also have some more evolved earthy notes. There’s plenty of richness all round, and it is surprisingly youthful (it was cellared from purchase). It went spectacularly well with a beef and mushroom rice dish in a red wine stock. Glorious.

I purchased this from the domaine in 2017. There are one or two occasional sightings of Becker’s top wines in the UK. Majestic Wines is an unlikely source for some of his less expensive offerings (their web site currently shows a “Pinot Noir” and I’m pretty sure I’ve seen a Weisser Burgunder in the past, so worth a look if you are ever in a Majestic warehouse).

Ora 2020, Annamária Réka-Koncz (Barabás, Eastern Hungary)

Although some of Annamária’s grapes are sourced from friends further west within Hungary, the grapes for Ora all come from her home vines at Barabás. It is, as the name gives away, a skin contact wine. It’s a blend based on the ever-faithful Királyleanyká variety (aka Feteasca Regala in Romania), with co-planted Rhîne Riesling, Furmint and Harslevelu.

The 2020 comes in at just 11% abv (the 2021 has an extra one percent). The colour is very orange and there is the expected texture and a bit of tannin, but it’s balanced by a lovely richness you might not expect at this lower level of alcohol. I got apricot and mango dominating the bouquet, with the palate pretty similar. It has a nice long finish too. It’s an exciting wine, and a perfect match for a risotto of kabocha, oyster mushrooms and fennel. It did no harm that the wine and the kabocha flesh were pretty much the same colour.

This came direct from importer Basket Press Wines. As always it has sold out, so you need to be in the loop as to when Annamária’s next shipment will be. Prost Wines often has stock after they have sold through at Basket Press.

Quand Le Chat N’est Pas Là 2021, Jean-Pierre Rietsch (Alsace, France)

Jean-Pierre farms twelve hectares of vines, mostly in and around the geranium-bedecked village of Mittelbergheim, in the northern part of Alsace, between Andlau and Barr. He’s almost an old-timer now, having taken over from his parents in 1987, but he still doesn’t seem particularly old to me, despite approaching his fortieth vintage. May he have many more.

His wines are as beautiful as his ever-changing labels, though it does mean in that case you need to see the back label details to know specifically what you are getting. That said, you should know that whatever you purchase you are going to drink some of the finest natural wines in the whole of France. Sulphur is rarely used in this cellar, but Jean-Pierre will add a tiny amount on those occasions he deems it absolutely necessary.

This wine, whose name is a play on “when the cat’s away…” (the label artwork making it quite clear), is a single varietal Pinot Gris. It comes from the sand and limestone (calcaro-gréseux) soils of the Stierkopf vineyard at Mutzig, a little way further to the north, just west of Molsheim. J-P produces a number of wines from this site, including Pinot Noir.

The cuvée used whole grape maceration for nineteen days, so there is a pinkish tinge in the wine from the skins. J-P was something of a pioneer in Alsace in using skin contact to help make dry wines from the aromatic varieties here. Ageing is seven months in foudre. No sulphur is added to this completely “natural” wine.

Along with its pinkish hue, we have some gentle red fruits on the nose, so blind-tasting in the traditional sense you might well think it’s a delicate red wine. However, the intense minerality here is definitely that of a white wine. The acids give the wine a brightness on the palate, combining so well with the concentrated fruit. This makes it so “drinkable”, especially as unlike many an Alsace Pinot Gris, this has only 12.5% alcohol yet is dry.

When it comes to my Wines of the Year for 2024, I am really going to have considerable difficulty in choosing between five out of six of this small group of wines for November’s selection. That in no way detracts from the pleasure and fun I had from drinking the sixth, the Pataleban from Nepal.

Imported by Wines Under the Bonnet, this bottle coming from Cork & Cask in Edinburgh. Price: about £30. Cork & Cask has sold out but the importer is listing the 2022 now.