For those who may not know, or have forgotten, the format we have is a case of wine here, twelve bottles, one for each month. Each is carefully chosen. Occasionally a few rivals will get a mention. As with my “Recent Wines” articles every month (and December’s version in two parts will follow shortly), I’m listing what I think are the most interesting and exciting wines I drank each month, not necessarily the finest, although quality is a given.

So here below, twelve stimulating wines from twelve different regions. Those are Beaujolais, Vermont, South Wales, Mosel-Saar-Ruwer, Nepal, Savoie, Moravia, Burgenland, Vienna, Hampshire, Piemonte and East Sussex. That is twelve wines from the 145 I wrote about in 2025 in my Recent Wines articles. Aside from the fact that 145 bottles (plus those I omitted) represent a horrendous annual wine budget, it also represents a lot of tasting experience over a very wide world of wine.

If what you read about here seems a little different to the mainstream and piques your interest, you can be assured that you will likely get similar good value from these articles on wines we drank at home, which appear every month on wideworldofwine.co, alongside other pieces on the vineyard visits, wine tastings, book reviews and other wine- (and cider, whisky, etc) related adventures I get up to.

JANUARY

Beaujolais-Villages “Wild Soul” 2021, Julien Sunier (Beaujolais, France)

Drunk at the end of January, this “summer” Gamay was on top form. I chose this, a simple wine in many ways, for its life-affirming fruit (strawberry and cherry) and its soaring floral bouquet. A natural wine, though in no way challenging for more conservative palates, this is simply outstanding. The most exciting of a number of great Beaujolais I drank last year. Good Beaujolais just seems to deliver so much for so little money. It cost £23.50 from Berry Brothers.

FEBRUARY

Damejeanne Vermont Rouge 2019, La Garagista (Vermont, USA)

Deirdre and Caleb have been ripping up the rule book on hybrids etc for about sixteen years, as well as pursuing regenerative farming with admirable results. The grapes (90% Marquette with 10% La Crescent) are grown in the Champlain Valley in Vermont, the long north-south lake here extending into both New York State and Québec, Canada, as part of the St-Lawrence River drainage basin. Five weeks on skins for this cuvée, then aged in 25-litre demijohns. Another natural wine. Brambly, Alpine, but above all, very distinctive, very alive. From Les Caves de Pyrene at the last Real Wine Fair.

I might have chosen Dobrá Vinice’s Nejedlik Orange 2011, a stunning fine wine from Czechia which came from Basket Press Wines, but you won’t likely find a bottle now.

MARCH

TAM 2023, David Morris/Mountain People Wines (Monmouthshire, South Wales)

David of course used to make wine at his parents’ Ancre Hill. Since branching out alone, his wines have become even more dynamic. He is very talented. This Chardonnay is sourced from Somerset, but it is a dead ringer for Arbois. Fermented in a Stockinger barrique, then twelve months on lees, only 270 bottles saw the light of day. Zero added sulphur, very fresh, it reminded me of Stephane Tissot. This wine was available from Spry Wines and, via a different bottling and label, from Cork & Cask, for £37.

APRIL

Elbling 2021, Jonas Dostert (Mosel-Saar-Ruwer, Germany)

How come I chose this varietal Elbling over other April gems such as Laissagne’s “Le Cotet” and Stephane Tissot’s Amphore Savagnin? Well, Jonas is a rising star. His wines are hard to find in the UK because people have not quite cottoned-on to just how good he is…yet. And you know what they say – judge a great winemaker by his entry-level wines. His vineyards opposite Luxembourg are on limestone, not slate. Elbling is an unfairly maligned variety. The usual story, over-cropped and bulk produced in the past. The 861 bottles of appley, mineral refreshment created here show how unfair that assessment is. Brittle, but in a good way. Try Newcomer Wines (£29), or Feral Art et Vin in Bordeaux.

MAY

Rose Koshu 2024, Pataleban Vineyard Winery (Kathmandu Valley, Nepal)

It might seem a bit pretentious to include a wine that you really won’t have much chance of finding outside Nepal, but hear me out. Pataleban has a resort hotel with vineyards not far from the western edge of Kathmandu’s urban sprawl (nice food, nice walks), and a winery located further west (anything from thirty minutes to ninety depending on traffic). They grow a mix of vinifera and hybrids on a number of sites at between 750 to 1,600 masl. Koshu was planted in the early days following initial help from Japan. This is vinified as a Rosé (Koshu has pink skins). It’s possibly not the best wine they make, but it is massively fruity with a deliciously fresh mouthfeel, and a good example outside of Japan of a variety which can be so much fun. Worth seeking out when you head to Nepal.

JUNE

“Kheops” 2016, Les Vignes de Paradis (Savoie, France)

This is what I opened for a sommelier/wine consultant friend when they asked for something “electric”. From Savoie, close to Lac Léman, within the appellation of Crépy (but resolutely Vin des Allobroges IGP), this is the wine Dominique Lucas makes from biodynamic Chardonnay under a regime dictated by the planets in a replica, made from local materials, of the Pyramid of Khufu. Dry minerality, soft texture, lemony acidity and a vibrancy you will be hard-pushed to find anywhere. Just 690 bottles in 2016. Thankfully I have one more to share. £45 from The Solent Cellar, via importer Les Caves de Pyrene.

JULY

Black Horse 2022, Pétr Koráb (Moravia, Czechia)

Koráb makes some of the finest petnats I know, and he has a real knack with red ones. This was my last of three Black Horse, a blend of Amber Traminer, Karmazin (aka Blaufränkisch) and Hibernal, made by the Ancestral Method in a mix of robinia wood barrels and ceramic vessels. It’s not disgorged. It’s all strawberry, raspberry and cranberry, so a perfect summer sparkler. Fun but equally interesting for wine obsessives. Not sure whether Pétr will keep making this, he’s like that, but fear not. He’s a petnat genius and so anything he makes in that direction will likely be as stimulating. This cost just £26 from Basket Press Wines.

AUGUST

Josephine Rot 2017, Gut Oggau (Burgenland, Austria)

August was the hardest month to select a winner from. Hot (very hot) competition came from two Vin Jaunes (a 2010 Touraize and a 1986 Le Pinte), Duhart-Milon Rothschild 2000 and my last 2000 Clos des Goisses. Gut Oggau won because their wines are etched deep in my soul. Also, Josephine is a good bridge between excitement and stature in the GO “generations”, and it is also a good example of what Rösler can add to a blend. A purple wine off a south-facing limestone slope. The tannins have largely departed but the fruit intensity has not, nor its crisp freshness. Elegant, and so, so alive. Recent vintages will be in the range £60 to £70 from Dynamic Vines, or from Antidote Wine Bar (near London’s Carnaby Street, take away).

A mention in despatches must go to “Les Arceaux” 2021, a unique Rosé made from Grolleau Noir and Gris by Alice and Antoine Pouponneau at their Grange Saint-Saveur in Anjou. From a man who consults at Cheval Blanc, this was a genuinely remarkable find at Communiqué Wines in Edinburgh (via Thorman Hunt). This must rank as the most exciting Loire wine I’ve drunk for several years.

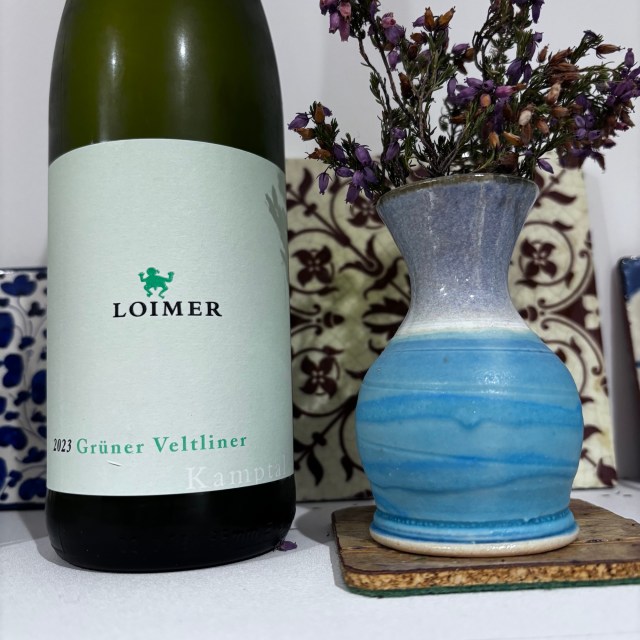

SEPTEMBER

“Rakete” 2022, Jutta Ambrositsch (Vienna, Austria)

I feel that 2025 saw me drink fewer Austrian wines than usual, yet two have made this selection (and others, like Knoll’s fine Wachau Ried Kellerberg 2011 haven’t had a look-in). Jutta makes my favourite wines from what is visually one of my very favourite wine regions in the world, the hills on the edge of Austria’s capital. This is a typical gemischter satz-type field blend, but is 80% Zweigelt. Five rows of vines fermented in stainless steel. A wine with a nice grainy texture and a grapefruit bite, chill well and shake up the sediment before pouring. Now around £25 to £30 from Newcomer Wines.

OCTOBER

Promised Land Riesling Brut Nature 2017, Charlie Herring Wines (Hampshire, England)

I did think twice about including a wine I consider still a little young, but the quality and the potential is off the scale, making me feel better about doing so. Tim Phillips grows his Riesling within his walled Victorian “Clos” just west of Lymington, the protection of the walls creating a micro-climate mirrored on a macro scale by the weather-break that is the Isle of Wight. There’s more fruit now it has aged a little, not so much on the nose, but the palate explodes with it. Thrilling to drink now for Winzer Sekt-loving acid hounds, but worth keeping that last bottle from a tiny production if you have one, most of which is snapped-up by trade insiders to be honest. £40 from the winery (open day is once a year), otherwise keep a lookout at The Solent Cellar or Les Caves de Pyrene.

I also have to mention the new “Village Chardonnay” from Westwell in Kent. Genius from Adrian Pike, and hardly over £20 at Cork & Cask, Edinburgh.

NOVEMBER

Barolo 2010, Giacomo Fenocchio (Piemonte, Italy)

Another exceptionally strong month with Lilbert 06, old Robert Michel Cornas, Lambert Spielmann and Alice Bouvot (her L’Octavin P’tit Pousset 2016 was sensational), but this Barolo topped them all. This is Giacomo’s entry level wine, yet it offers everything someone at my pay grade could want from Nebbiolo. Based at Monforte d’Alba, this is a producer others call a traditionalist, although the Barolo wars (trad v modernistas) were really just hype. However, this was certainly built for age, and even in late November there were still many more years of life in this 2010. There are still some tannins, but to highlight just one of this wine’s qualities here, these were the most beautiful tannins I have tasted in a long time. No longer available, I scooped a few of these from The Solent Cellar way back. The next bottle I will attempt to keep a few more years to see whether time adds something more haunting, but no question, this is a great fine wine now.

DECEMBER

Blanc de Noirs 2018 Cuvée Noella, Breaky Bottom (Sussex, England)

Although you won’t have read my notes yet on the twelve bottles I have selected for my “Recent Wines” articles covering December, you might not be surprised that I chose this one to represent that month. I’ll leave the details for now, but this was the first time that Peter Hall had been able to make a cuvée from only red grapes (Pinots Noir and Meunier). It is of course a wine of exquisite finesse, drinking nicely though with room to grow. We said goodbye to this humble man last year. No one had contributed to the soul of English wine like Peter. Breaky Bottom under his direction remains a beacon of artisan winemaking in England, where quality and beauty went hand in hand. Corney & Barrow are agents for BB, but all my supplies have always come from Peter’s great friends Henry and Cassie, at Butlers Wine Cellar in Brighton.

It only remains to wish everyone a Very Happy New Year and a wonderful 2026. It may have started cold, and perhaps a little frightening, but may we all find the strength to make the world a better place…whilst enjoying some more cracking wines like these.