I read quite a few wine books each year, or at least when the publishers drip feed them to us. Some are general books, some specialist, some are an easy read and some require focus and concentration for every paragraph. One Thousand Vines definitely falls into the second category in each of those cases. But this is a very important book. We had a work of similar importance last year in Jamie Goode’s The New Viticulture, and like that book, this one requires all of your attention whilst reading. However, in its scope and depth I would agree with those before me who have said that there has really been nothing quite like it in wine writing before.

Pascaline suggests she tried to write the book that she wished had been out there when she began learning about wine. Well, I’m sure Pascaline, with her honed intelligence, would have devoured it. I certainly did, although it is not a book to read when your eyes are drooping and you are ready for sleep.

Pascaline Lepeltier comes from Angers in the Western Loire. Her university studies led her to a master’s thesis in philosophy, but then she needed a break. A teacher suggested she go and work in a wine shop, and this is how Pascaline discovered her true calling. She worked restaurants as a sommelier in Belgium and then in the USA, where she is now Beverage Director at the famous Chambers Restaurant in New York’s Tribeca district. She has many other roles, which enable her to travel widely, but at Chambers she has put into practice her, shall we say, wine philosophy in creating an astonishing list of 3,000 wines, most of which are organic and/or biodynamic.

Pascaline Lepeltier is known as one of the foremost sommeliers in the world, but at the same time she is also known as one of the most influential advocates for what I would like to call the modern philosophy of winemaking and wine appreciation. This book is not a bible merely for those who share this philosophy, but its holistic approach weaves such themes into the narrative in a way that few (perhaps only Dr Goode, from whom she draws quotes from time to time) have attempted before.

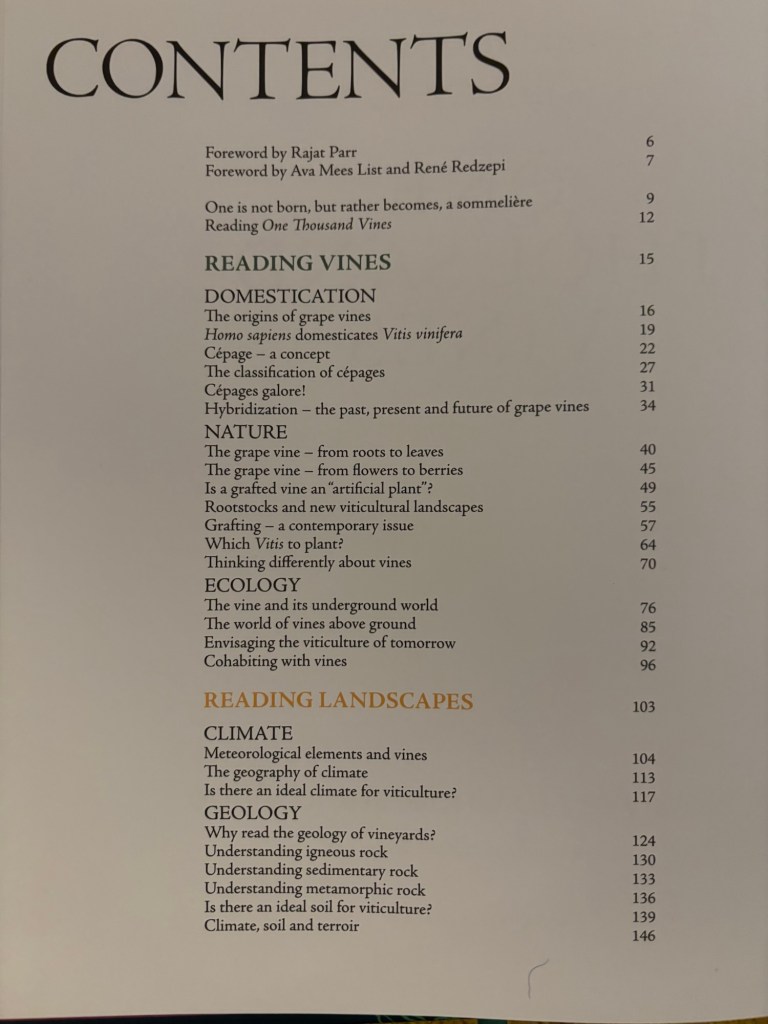

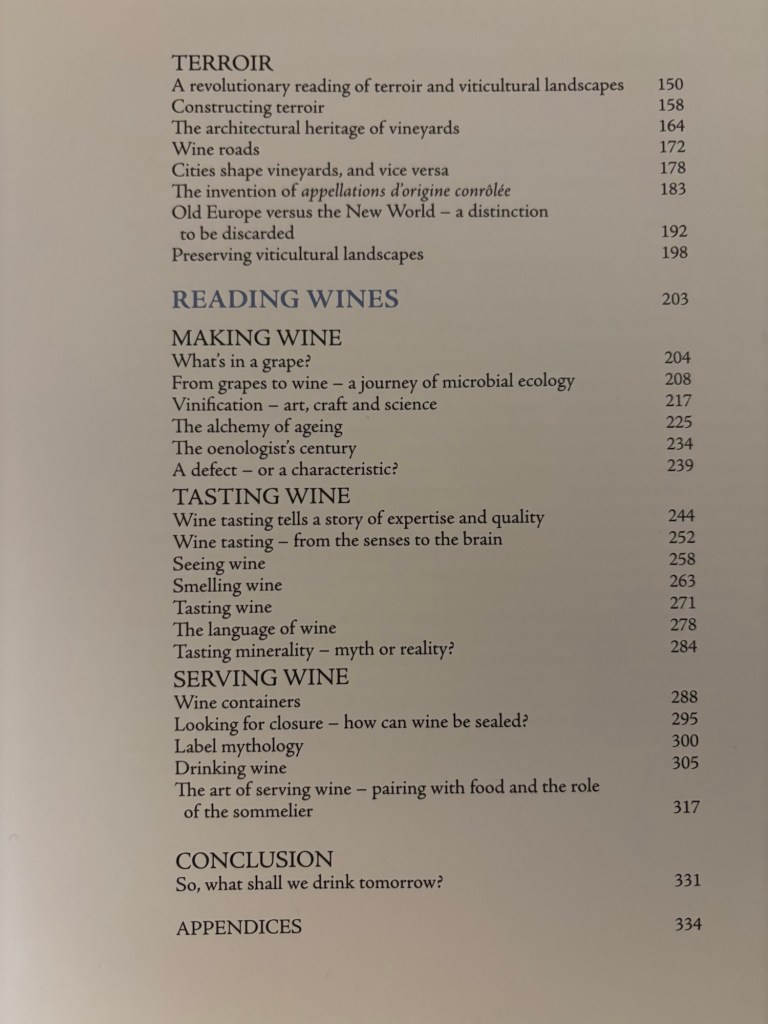

So, as you can see from the table of contents (below), we have a work which covers Vineyards (the domestication and nature of the vine and its place in a wider ecology), Landscape (climate, geology and terroir), and Wines (winemaking, wine tasting and serving wine, not to mention marketing).

The detail the author goes into is amazing. Much of the reading is scientific and technical and although all her explanations are easy to understand, the reader does need to immerse themselves in the text and at times proceed quite slowly to fully take it all in.

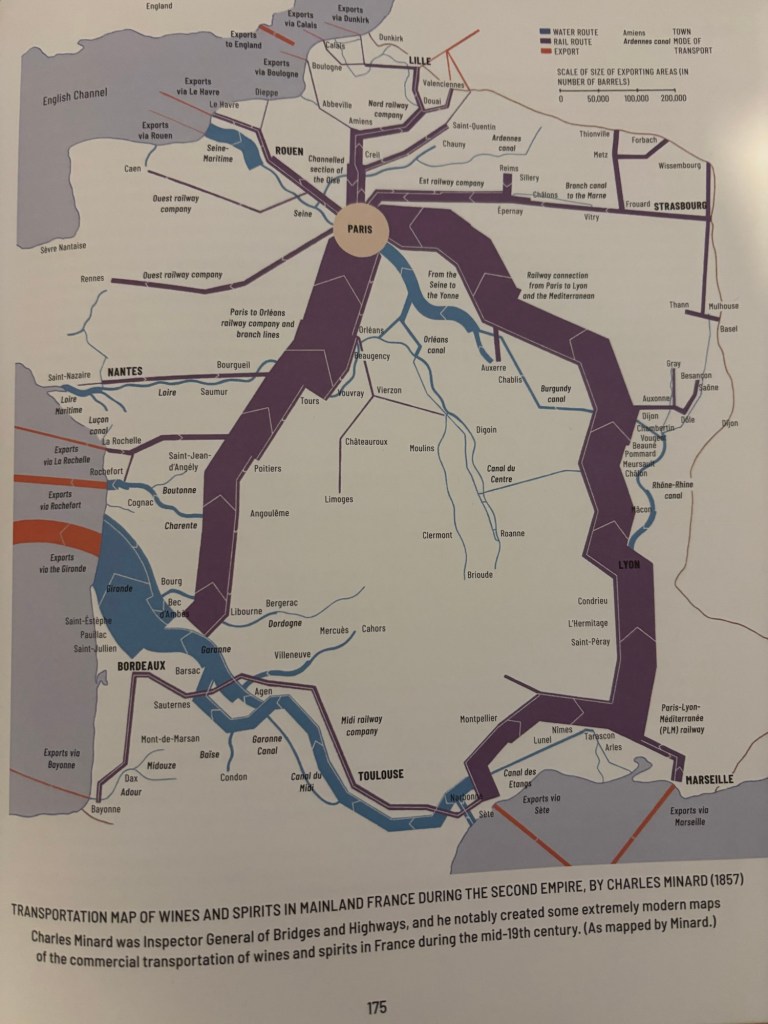

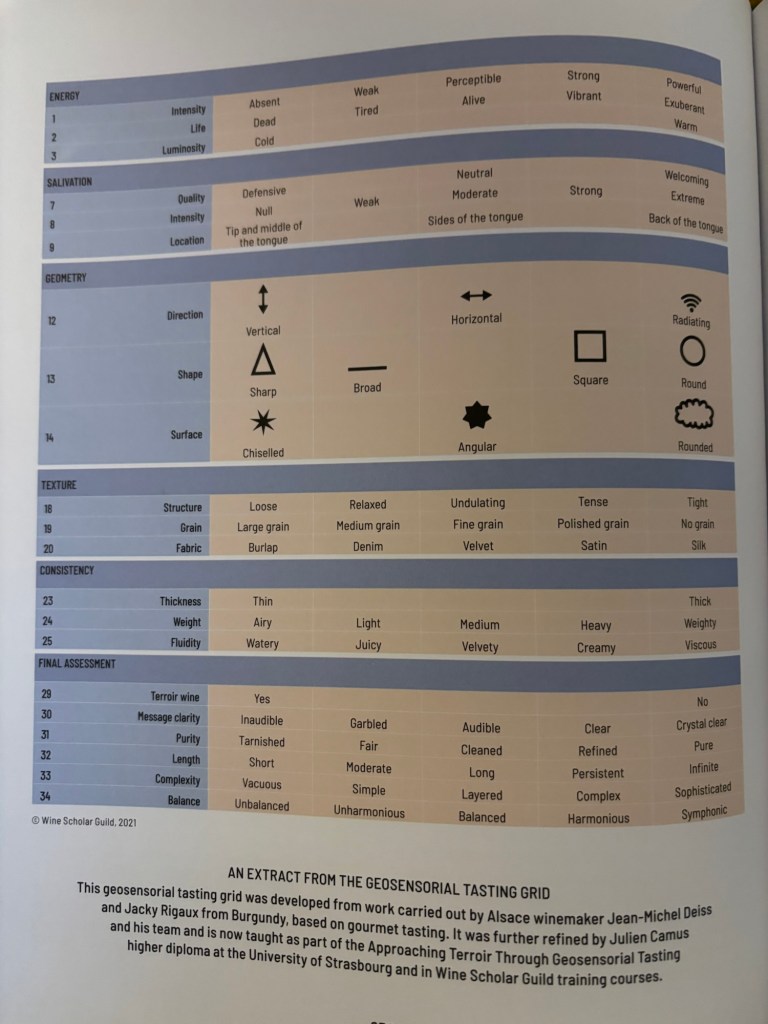

The text is accompanied by maps and other graphic illustrations which supplement the text, illustrating points made and concepts explained. There are no superfluous photographs, no pretty pictures. What you get resembles a text book, for this is a serious work. It doesn’t read like a textbook though.

The first two thirds of the book are perhaps the densest read in terms of imparting deep technical knowledge, although always in an engaging and readable way. Always, within the detail, we see Pascaline’s philosophical mind working, questioning and broadening the subject matter, especially to take in the most current thinking.

One such example is the reminder that viticulture is in no way just a random use of nature’s bounty. Vines are imprisoned in vineyards, tethered to stakes and wires. That’s not quite how the author puts it, exactly, but a few contemporary-thinking vignerons, perhaps Florian Beck-Hartweg in Alsace, or Oszkar Maurer in Serbia might say that. But Lepeltier does examine the nature of vineyards and different ways of looking at them.

Lepeltier certainly makes very clear man’s influence over nature, exposing so many myths, such as (for example, inter alia) one about terroir. That the most famous vineyards have always been located close to markets because, er, obviously, they needed to sell the wine in a time before railways and road transport made longer and more difficult journeys possible. This might mean, in France, the easy transportation of wine by waterway (first rivers, then canals) to Paris, or it might mean export markets by sea (in the case of Bordeaux). So perhaps this idea of perfect terroir for growing vines is not quite the absolute we presume. It isn’t that terroir, in the narrow, traditional, sense doesn’t matter. It’s just that the author is always throwing a curved ball, or saying to us “but what about…?”.

The scope of the book is immense. In all of the three distinct sections we are taken as far back as Ancient Egypt, through all of history to the present day, or to be accurate to 2022 because this book was first published by Hachette in that year, this English edition being a translation.

Pascaline being French, you will find a strong focus on the development of viticulture, winemaking and everything that goes with it, in France. To be fair, France has had probably the greatest influence on wine from medieval times until the start of the 21st century. That said, she doesn’t ignore other influences, such as to some degree the rise of the Asian market, but more importantly Anglo-Saxon influences which have grown in importance since the late 20th century. These encompass everything from English glass to Robert Parker and beyond.

We also see the author addressing issues which have only arisen in the past ten, twenty, or fewer years. Such issues are naturally strongly related to the influence of the natural wine movement. When natural wine became part of my own consciousness in the early 1990s, I always argued that it is those working at the periphery of wine thinking, those doing the things considered “out there” by many (and considered blasphemy by a few enraged old men) who are pushing the boundaries.

We see the movement’s influence has indeed been significant, and is increasing. It has influenced the way we think about soils, additives, so-called wine faults, about methods of transport and what vessels we sell wine in, and much more. Perhaps even more important than that, natural wine has made us think more openly about how we define quality in wine, and indeed how important some measure of quality might be. I mean, I’m not suggesting anyone should be drinking “bad” wine. Simply that in pursuit of always “the best” we will surely miss out on the experience of tasting “the most interesting”. I’m pretty sure that Pascaline would agree.

My own blog, wideworldofwine.co , is not only dedicated to wine from a wide geographical area, but also to a broader way of appreciating wine. Of course, I love a fine Burgundy or Bordeaux, but I am glad to taste the wines of Japan, Nepal, Armenia or Serbia and I derive as much stimulation from doing so as from a well-cellared fine wine at its peak. I’ve been blessed to drink many of those, and doubtless I shall, if lucky, drink many more. I’ve never tried wine from Ukraine though (yet).

The Conclusion to One Thousand Vines is sub-titled “So, what shall we drink tomorrow?”. This three-page conclusion begins with a stating of a stark fact. Urgent action is required to address the environmental (and one should add, economic) problems viticulture and wine face today. Wine faces threats on all sides, from the anti-alcohol lobby to wine speculation by the rich making good wine so much less affordable to the consumer, especially the discerning consumer who might otherwise fall in love with a well-crafted artisan wine.

As the author says, “wine…holds up a mirror to our civilisation: its crises are our crises, its status and the way it is defined are our social choices…” Wine is no longer what it was, neither a safe food, providing calories when water sources were unsafe, nor is it the cultural “totem” of societies like France and Italy. It has become on the one hand an industrial product shipped around the world and sold in supermarkets, but equally, a collector’s item which is fast becoming too expensive and unobtainable for those passionate about exploring it.

Pascaline Lepeltier suggests that the way forward for wine lovers is through “[r]ediscovering the taste of living wine as an eminently joyful and political act of resistance”. I would agree, although I should point out that those working in wine, those who get to taste and drink wine as part of their job, and indeed to purchase it at a discount or to be given free samples, do sometimes forget that natural wine is of its nature in a wholly different price bracket to the beverage, commodity, wine we see on the shelves of the supermarket. Using a UK yardstick, much supermarket wine will cost below £10 per bottle. I am very lucky if a bottle of my political act of resistance costs me less than £30. Often it is more in the £30-£50 range.

Are there any negatives with this book? Not really. I always get annoyed by proofreading and typographical errors and there were enough here to surprise me, given the prestigious imprint it appears under. That said, such errors probably amount to no more than a dozen or so in nearly 350 pages of text. I think that £45 is expensive and no one has addressed this. I presume most reviewers were sent a free copy. My desire to use local indie book shops means my copy was neither free nor discounted, but at least my own political act of resistance here is to ensure the author gets a fair share of the proceeds (I hope). It’s why I don’t use music streaming services either.

In his Foreword, US sommelier and winemaker Rajat Parr sums up with the following sentence. I could not put it better. If you are sufficiently passionate about wine that you are keen to dive deep into its wide world, then you must find a way to afford it. “This book is destined to become essential reading in the wine world. Reading it once or twice will not be enough; it will be a weekly or daily reference. If you have never [like me] met Pascaline, this book reveals her soul [I think it probably does].”

One Thousand Vines is published in English by Mitchell Beazley (348pp in hardback, 2024, £45). It was first published by Hachette Livre in French in 2022. As you will have deduced, for my average reader/subscriber this will be an emphatic “buy”… if you can afford it. For me it’s like that wine that is definitely over budget, but you just have to have it.