Hobbes versus Rousseau. We find this conflict almost everywhere these days, especially in global politics. Hobbes favoured the rule of law in an almost Old Testament sense, the structures of the state (Leviathan) providing the only way to keep we wicked humans on the straight and narrow (ie, under control). Rousseau was more for freedom (within the context of his time), showing the value of individual thought and action. So, what on earth has all this to do with Champagne’s Grower Revolution? After all, Rousseau gave us The Enlightenment, and the great leaps in Science, Philosophy and Literature which stemmed from that movement are somewhat more important than the economic emancipation of a group of French farmers.

Back at the time of creation we wandered the globe as free beings, but not the Champenois farmers when the regulations were laid down for the AOC. No, when “Champagne” was created, it was run by the Champagne Houses, who over time (bar a few riots thrown in by the paysans) tightened their grip on this largely viticultural region in Northern France. They not only dictated which vineyards were to be part of their region, they also dictated the price paid for grapes. The people who grew those grapes were most certainly the peasants and the negociants were the aristocracy.

When I began drinking Champagne it was all about the Houses. Apart from anything else, the power of these large movers enabled them to write the story of Champagne, and part of that story is that Champagne has to be a blend of different grapes from different villages, in different parts of the region. The whole is superior to the sum of the parts. And we probably won’t tell you what those parts are!

Forget the fact that many of the big Champagne Houses, the Grandes Marques, have pretty much made single vineyard Champagnes for decades: Taittinger, Bollinger, Philiponnat, and the biggie, Krug, to name only four. Pretty good they are too. Now I’m not against the Houses at all, and nor would I try to argue that Grower Champagne is better than that made by a Grande Marque. What I do argue is that by exploring the Growers one can learn so much about the region as a whole, through what are indeed diverse, individual and highly interesting terroirs. Even if you were to decide that the “blend” of sub-regions is better than the single terroir, wouldn’t it be instructive to see how they express themselves tout-seul?

What I would like to do is to introduce you to some Growers. Many of you may not merely have heard of all of them, but will have drunk wines from them. This would come as no surprise. All of these producers are making wines potentially as good as anything bottled in the Champagne Region. I initially wanted to put together a nice neat mixed case of a dozen wines from a dozen different producers, but that’s always too difficult for me. My compromise is a baker’s dozen, thirteen, with a few honourable mentions tacked on to the end. My excuse…one of the wines chosen below to represent our Grower Revolution is not sparkling.

Francis and Delphine Boulard, Massif de Saint-Thierry

We will start in the region’s far northwest, just off the A4 Autoroute from Reims to Paris, and at the village of Neuville-aux-Larris, where at that time Francis Boulard made Champagne under the “Raymond Boulard” label. It was here that I visited on the way home one late summer’s morning having come across his Champagnes in a shop run by the now owner of Tillingham Wines in the UK, Ben Walgate. Francis very soon went his own way, joined by his daughter Delphine. They are now based at Faverolles-et-Coëmy, and still make most of their cuvées from grapes off the Massif de Saint-Thierry, labelling them Francis Boulard et Fille. Although this is possibly one of the least known names in my selection, I would say that these were very possibly the most terroir-specific Champagnes I had ever tasted back in the mid-2000s.

I could have recommended the Boulards’ “Petraea”, made in a cuvée perpetuelle (a little like a solera), but I shall go with the biodynamic Chardonnay beauty that is “Les Rachais”. The Chardonnay vines forming this single site wine are fifty-four years old now, planted on sandy silex/limestone terrain on the Massif, fermentation in fairly old barrels and dosed Extra Brut (circa 2g/l). This is a wine of genuine mineral purity, which Michael Edwards called “ethereal” when speaking of my favourite vintage for this wine, 2002 (it was first produced in 2001). A cuvée one should only think about disturbing from the cellar after ten years.

Jérôme Prévost (La Closerie), Montagne de Reims

Prévost was initially most famous for being one of the first so-called disciples of Anselme Selosse (who we shall come too in a minute or two). His tiny estate (originally two hectares) is at Gueux, where he began making wine in 1998, initially sharing winemaking facilities with his friend, Selosse. He started out making one wine named after the single vineyard from whence it came, “Les Béguines”. The wine, aside from being eye-wateringly good, was unusual at the time in that it was made from 100% Pinot Meunier, the much-maligned member of the Champagne grape trio.

However, this is not the wine to sneak into my baker’s dozen. That is Prévost’s second cuvée, “Fac-Simile”. This is also pure Meunier, but is a Rosé. I say Rosé, but like another wine listed below, it is pale. It has a haunting quality which stems from the small but concentrated dash of red wine added to the straight white “Béguines” to make the wine tinged with a rusty pink colour. It’s a wine which sometimes smells of red fruits and sometimes of tea leaves, sometimes a minute apart. It’s capable of real complexity but in that subtle way that emerges in the (preferably large) glass over time. Coming off very complex soils which include limestone, chalk and sand, all packed with the compressed remains of marine fossils, this is hardly surprising.

Bérêche et Fils, Montagne de Reims

Of all the growers in Champagne the one I’ve enjoyed building a relationship with the most is the very friendly Raphaël Bérêche (and his mum). I’ve been entertained with tastings at their winery on top of the Montagne, at Le Craon de Ludes, on several occasions and have been able to get to know the whole range. Raphaël and his brother, Vincent, farm just less than ten hectares spread over the mountain and the valley of the Marne. Everything is done here gently, but with care and attention to detail, perhaps most exemplified by the fact that they insist on using real corks rather than crown caps for the second fermentation of the top cuvées. I also remember visiting when the new Coquard vertical press had just arrived, and another time an optical sorting table, ahead of its time.

Every wine made here, from the Brut Réserve upwards, is worthy of inclusion. The Rosé here, “Campania Remensis” (from Ormes) is a particular favourite, as is “Le Cran”, a vintage blend of two vineyards at Ludes (Cran = Craon). They also make what is my favourite still wine (Coteaux Champenois) from Champagne with Pinot Noir from Ormes. That’s even before we mention some stunning negociant wines. But I’m going to choose a wine which has long been my favourite here, “Reflet D’Antan”. It’s another wine from a cuvée perpetuelle, which Raphaël insists is not a solera! It was discontinued for some years when, in order to make it even more complex, they decided it should have longer lees contact. It now gets 36 months sur lattes. In some ways it is a kind of marmite wine, in that it has some oxidative notes which its UK importer (Vine Trail) suggests may be reminiscent of Jura wines (being a massive Jura-phile that doesn’t worry me). It’s also very honeyed with age and remarkably complex. Certainly it’s a gourmet wine to be savoured in a wine glass, and perhaps thrown (gently) into a carafe for a while beforehand.

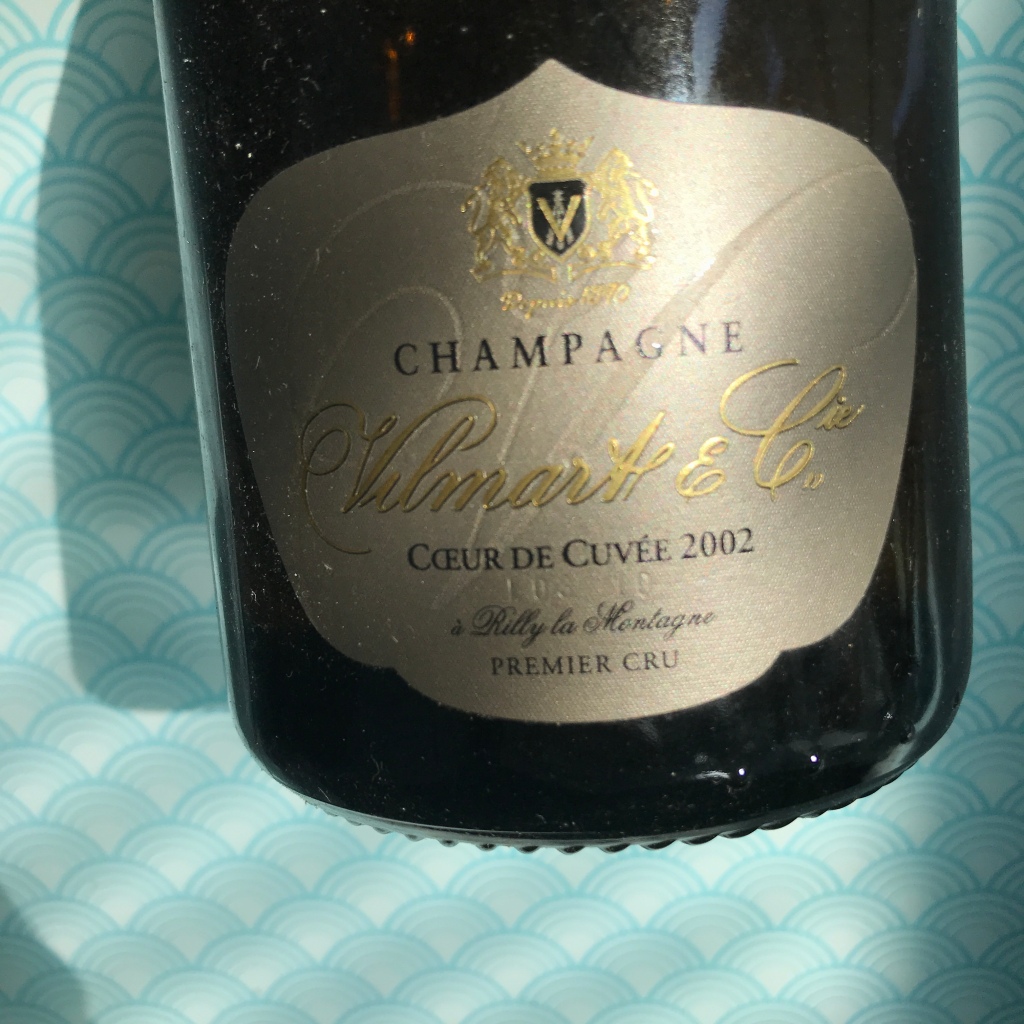

Vilmart et Cie, Montagne de Reims

I strongly recommend a visit to Vilmart if you can arrange one. Their cellars at Rilly-la-Montagne are not just impressive for the wines, nor just for the large wooden barrels and vats which adorn one part of the building, but for the rather beautiful stained glass all around you, created by René Champs, father of current incumbent, Laurent Champs. This is another very focused producer. The old vines may all be mere Premier Cru (no Grand Cru vines here), but they are cared for meticulously (even tilling by hand). The result at the top end is almost miraculous quality.

“Coeur de Cuvée” is the top of the range at Vilmart. It is made, of course, from the heart of the first pressings. Fermentation is in small oak (222-litre barrique). Such wines require perhaps a decade to feel fully integrated. At fifteen to eighteen years, depending on vintage, and with a good swirl in the glass, it comes together. By twenty years of age, you may feel it is close to perfection (others may prefer it younger). The blend is usually around four fifths Chardonnay to one fifth Pinot Noir. Expect a vinous wine with nuttiness predominant. This is a classic, and in my opinion, forgotten by many of today’s “influencers”. It is also a regular bet in so-called off vintages.

Lilbert et Fils, Côte des Blancs

Bertrand Lilbert is the current young head of this historic Grower. The family began growing vines around Cramant, at the northern end of the Côte des Blancs, in the mid-eighteenth century. He farms in Cramant, Chouilly and Oiry. The style here is quite strict, the wines being almost piercing in minerality in their youth. It’s the acidity and mineral spine which gives the vintage wines their longevity. In some ways they are the essence of chalk on a blackboard.

I remember tasting here early one frosty late winter morning. The wines struck the palate like a needle. I was thrilled, not because I’m some kind of masochist, but because these wines reminded me of a complex-structured but filigree snow crystal, and I could foresee how they might develop (it was the 2006 vintage). I could have suggested a rather unique wine genre made here, called “Perle”. The style used to be called “Crémant de Cramant” and is bottled at just 4 atmospheres pressure, rather than the usual six for traditional Champagnes. However, the 100% Cramant Chardonnay vintage wine is finer, an old vine cuvée which expresses the terroir of “Les Buissons”, which comprises 75% of the blend. But it’s another wine to age, so that the crisp acids soften and the chalk comes through.

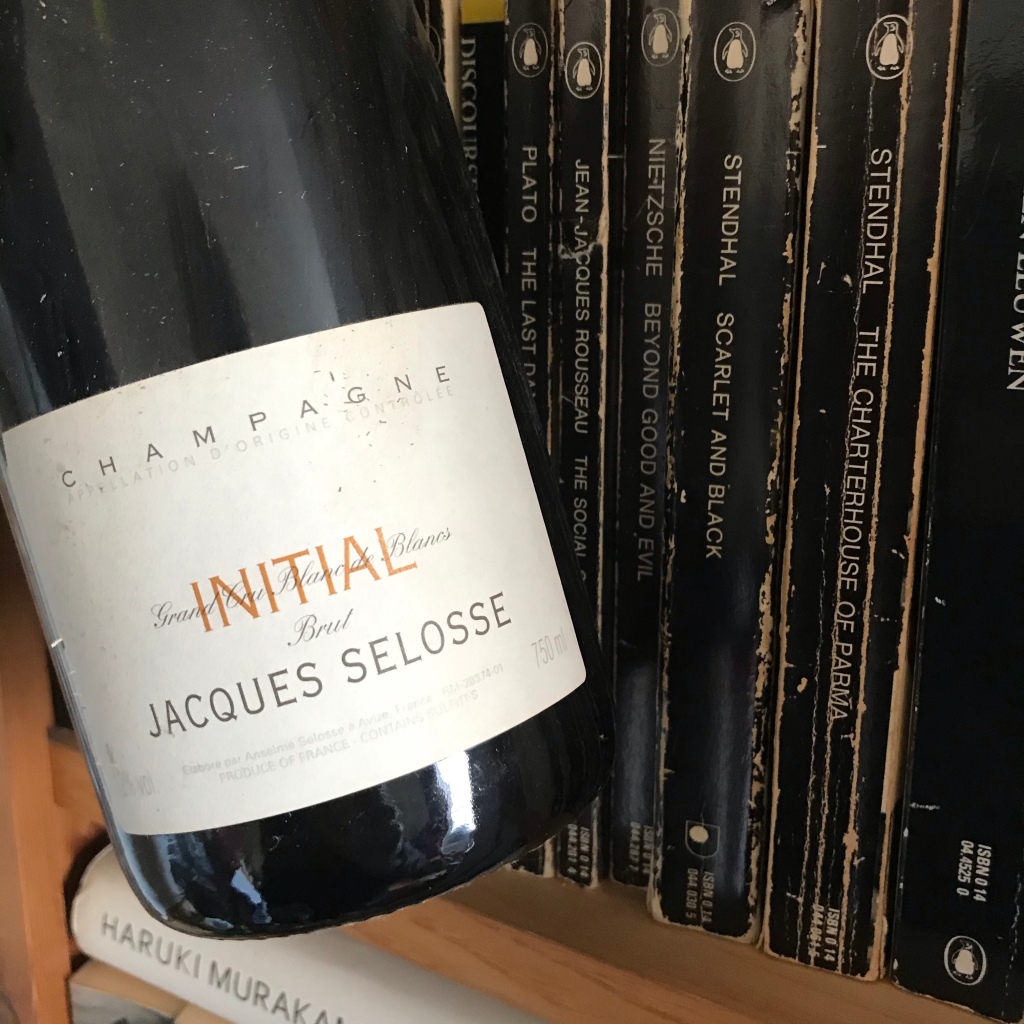

Anselme Selosse (Champagne Jacques Selosse), Côte des Blancs

I debated whether to include Selosse. Against – everyone knows him, his wines are horrendously expensive and anyone who dislikes the mere idea of Grower Champagne is just so negative. In the “For” camp, well, the guy pretty much single-handedly kicked off the Grower Revolution. If anyone has shown that Champagne is not merely one idea, and that other ideas are valid, this is the man. It was so long ago, 1974, that Anselme took over his father’s vines in Avize. He’d studied winemaking in Burgundy, not uncommon nowadays (almost de rigueur among the most terroir-conscious vignerons today), but rare back in the Seventies. Selosse was an early proponent of biodynamics in the region, but much more than that, he is a philosopher of what “Champagne” might be, and is capable of.

It is debatable as to whether the Champagnes Selosse creates are really terroir wines, as some here undoubtedly are, but that’s far from the point. In choosing a wine to include I had to bear in mind their cost, illustrated by the fact that there are now no Selosse wines I feel I can afford to buy, at least when compared to other producers’ wines. But then I was lucky to be just about early enough in the game to get to know them. I’m going to choose the entry level “Initial” here. It’s made from the youngest vines on the estate, 100% Chardonnay from Avize, Oger and Cramant, off lower elevations with deeper soils.

It’s always a well put together multi-vintage wine, and arguably the most “normal” in terms of flavour profile. Oak aged, the wood always integrates, and it has that creamy palate which shouts Grand Cru Chardonnay. It still gives an intro to the Selosse philosophy, and if you can afford anything from this producer, this is the one you will most likely buy.

Champagne Pierre Péters, Côte des Blancs

François Péters was an early Champagne hero of mine, and he has been ably followed, since 2008, by his son, Rodolphe, farming just less than 20-ha from the family’s winery in the village of Le Mesnil-sur-Oger in the heart of the Côte des Blancs. This is yet another source for some of the finest Grand Cru Chardonnay going. The range is excellent at every level, and this used to be another favoured source for the lower atmosphere “Perle” style which goes so incredibly well with almost any food you care to try it with. However, at the pinnacle of the Péters pyramid is one of the consistently finest wines made in the whole region.

“Les Chetillons” was previously called “Cuvée Spéciale”, but the name now justly reflects the very spéciale vineyard from which it comes. The vineyard itself is situated on pure chalky soils at Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, and it’s a wine with a very chalky texture, almost the purest minerality imaginable. But again, you really need to be patient and age this, or at least in most vintages (the 2000 was really good, for my taste at least, but more forward than most). An example is the 2002 vintage. When this was shared a couple of years ago one Chétillons aficionado declared it still not ready, and I tended to agree. It was my last but one bottle…though I have one left. It would be hard for me to believe that there is, in a fine vintage, any cuvée in the whole of Champagne which is better than “Les Chétillons”, which makes it exceedingly good value even at the price one has to pay today.

Champagne Ulysse Collin, Coteaux de Morin

You’d be excused for not knowing where the Coteaux de Morin is, though you might be more familiar with the Coteaux de Sézanne, with which it is contiguous, forming the northern part of a string of vine clad hills south of the Côte des Blancs. Olivier Collin farms nearly 9 ha at Congy, though when he began, in 2004, he had one parcel and one cuvée. Like Jérôme Prévost, Olivier spent a short time working for Anselme Selosse in the early 2000s. The joke is that you started with Selosse. When he got too expensive you moved to Prévost, and when you could no longer afford him you bought Ulysse Collin. This was back when Selosse Initiale cost maybe £90-£100 and Collin’s then single offering, “Les Perrières”, was maybe £55. Today you will pay somewhat more, around £100 retail at least.

Although that cuvée formed my first several purchases, I am selecting “Les Maillons” today. The reason – we’ve had lots of Chardonnay and this is a Blanc de Noirs bottling. It is again a single site, and the wine reflects the quite different terroir. In part this is down to micro-climate, but even more so it is perhaps a result of the fairly unusual soils, rich in iron, around Barbonne-Fayel, down on the Côte de Sézanne. The resulting wine is quite full-bodied, not always a style I go for. But this wine is fantastic, a real gem of a terroir wine and worthy of your attention…even though I lament the way the prices have risen inexorably at this address. Sadly, I cannot find a photo of “Les Maillons”.

Champagne Jacques Lassaigne, Montgueux

Montgueux is another hidden sub-region, just outside the old regional capital, Troyes. If you believed the stories, you’d think Emmanuel Lassaigne spends all his time in Troyes’ famous natural wine bar, Au Crieurs de Vin, rather than in the vines, but that would be far from the truth for this most meticulous and committed Grower. I say grower, but Emmanuel is technically also a negoce, like the Bérêche brothers. He buys in around 30% of his fruit. In part it’s to ensure he has enough wine to make a living, but just as important is access to other Montgueux terroirs. He is the greatest living advocate for this tiny sub-region.

Montgueux is quite special. Its geology is unique (almost) in the whole of Champagne. It has similar chalk to the Côte des Blancs, but far older, and instead of marine fossils there’s lots of flint. The only other place I know which has a very similar geology in the region is another isolated hill, Mont Aimé, which anyone who has stayed at the hotel of the same name, south of Vertus, will probably know.

Montgueux has been called the “Montrachet” of Champagne, and Emmanuel Lassaigne’s “Le Cotet” is the finest explanation for that epithet. We have a single plot of vines between 55 and 60-years old within this individual vineyard, all Chardonnay, making a wine of intense minerality. It sings with citrus acidity in its youth but as it ages it fattens (the grapes are always picked ripe and the reserve wines come from a complex reserve perpetuelle). It’s another Champagne which you have to treat as a white wine with bubbles, serving it preferably not too cold in a good wine glass.

If you can’t find “Le Cotet”, grab a bottle of “Les Vignes de Montgueux”. It contains bought-in fruit and is an expression of Montgueux as a whole. It’s great value (though also note the cuvée mentioned among the recommended retailers, below).

Vouette & Sorbée, Côtes des Bar

Montgueux is technically part of the Aube, Champagne’s once ignored southern region, but when one thinks of the Aube it is in fact the Côte des Bar which springs to mind. The “Bars” in question are the twin towns of Bar-sur-Seine and Bar-sur-Aube. This region tends to be warmer than the rest of Champagne’s AOP, with a semi-continental climate, and the soils differ in that there’s a lot more Kimmeridgian limestone and marl with any chalk. The comparison would be closer to Chablis, which is a stone’s throw across the Burgundian border, rather than the Côte des Blancs, a good long drive to the north. Pinot Noir thrives here, and has long provided fruit for the sometimes-secretive Grandes Marques in Reims and Epernay. Yet perhaps the greatest of them, Krug, has never been sensitive about admitting to using Aube fruit in its flagship wine.

Bertrand Gautherot is a name we see too little when we speak of the great growers. This is because when he began bottling his own wine in 2001 he chose to name his domaine after his two vineyards near the village of Buxières-sur-Arce. Both are quite different, Vouette being on the typical Kimmeridgian soils, Sorbée being on Portlandian strata. All the vines are worked biodynamically and any manipulation in the winery is kept to an absolute minimum (indigenous yeasts, zero dosage and tiny additions of sulphur).

I was talking to an importer last year lamenting the fact that so often now I’m forced, for purely financial reasons, to become most acquainted with the entry level bottlings from the great growers these days. This is certainly the case with Gautherot’s wines. This is why my choice here is “Fidèle”. Instead of selecting an expensive bottle I’ve possibly only drunk once, I’ve gone for a wine which is, after all, one of my genuine favourites.

“Fidèle” is a Blanc de Noirs, 100% Pinot Noir, from vines in the Vouette vineyard. Although it’s an entry level wine be aware that it does need a little post-disgorgement ageing. Given a year or two in your cellar or wine fridge it blossoms. It’s still pretty uncompromising (as I think Peter Liem has called all the Gautherot wines), and another example of the way the Growers are increasingly making the kind of Champagnes we call “Vinous”, wines which complement food.

Cédric Bouchard/Roses de Jeanne, Côtes des Bar

I was very lucky in that Bouchard was imported into the UK by The Sampler, almost from when they opened. In those days the Bouchard cuvées seemed expensive, but affordable. That is hardly the case now. Every wine made by Bouchard is from a small single plot, almost as if they came from tiny Burgundian Grands Crus, not that the Aube was allowed any Grand Cru sites when they were classifying the Champagne vineyards in 1911 (GC ranks 100% on the old échele, PC ranks 90-99%, but most of the Aube manages just 80%, clearly ridiculous).

Bouchard works out of Landreville, which like Bertrand Gautherot’s Buxières, is in the Barséquanais (Seine), on the right bank of the river. There are, if I am still correct, seven small batch Champagnes made, all of exemplary quality and real personality. I know and love most of them but my favourite is called “Le Creux d’Enfer”. Yes, it’s time to introduce another Rosé, but like Prévost’s, it’s quite far removed from most examples of “Pink Champagne”.

Apparently, it comes from just three rows of Pinot Noir and, according to Peter Liem, is foot-trodden. The very pale colour comes from a short skin maceration. The result is actually, for me, one of the most sensually and at the same time, intellectually, stimulating Champagnes I know. My typical note would be “ethereal”. It reminds me most of fresh tea leaves, though whether this is green tea or fine Assam I’m not sure (or perhaps my favourite tea is more appropriate, that exquisite Blue Himalaya Oolong from Marriage Frères in Paris). It’s probably fair to say that the first time I drank it provided my most revelatory moment in all the time I’ve been drinking Champagne. Maybe not quite Dom Pérignon’s “I’m drinking the stars”, but close.

Okay, so the photo’s Val Vilaine, not Creux.

Marie-Courtin, Côtes des Bar

The vineyards of Polisot, where rising star Dominique Moreau grows her vines, stretch over both sides of the River Seine in the south of the Côte. This estate is however merely one very tiny part of those vineyards, less than three hectares, formed on a south-facing slope. There’s a little bit of Chardonnay, but it’s mostly Pinot Noir that Dominique has planted here.

What I like about Moreau’s wines, and probably in truth most of my favourite Aube wines, is that whilst they undoubtedly show in some respects typically ripe Aubois fruit, they are also pristine, even crystalline in their freshness and rapier-like qualities. They do, as I’ve said before but it applies equally here, love a bit of PDA (post-disgorgement ageing, a watchword in the Champagne section of the Crossley cellar – it helps that having so few of these wines I am never in a hurry to drink them).

I only really know two of Dominique’s wines, “Résonance” and “Efflorescence”. Résonance is the entry-level Pinot, vinified in tank, whilst “Efflorescence” differs in that it is a vintage wine, aged in used oak. I’m going to choose “Résonance” because I know it best, but also because the combination of ripeness and precision allows the wine to show the purity of its red fruits. It’s very refreshing. I think Dominique Moreau is making wonderful wines and I hope I can get to know all of her wines in due course.

Olivier Horiot, Côtes des Bar

My first visit to the Aube was when I was in my mid-twenties. I stopped for a night en-route to the South of France, visiting some friends who were honeymooning in a borrowed house near Les Riceys, a group of hamlets about as far south as you can get in “Champagne”. We were almost literally over the border from the town of Chablis. One of the three wine visits we all made the day after our arrival was to a producer called Morel Père et Fils. It was my first taste of Rosé des Riceys, a still pink wine made from Pinot Noir with its own appellation, which at that time was almost unknown in the UK. Over the years I returned to Morel to stock up. If you aged it like a red wine, it was pretty good.

I nearly said “amazing”, but it was more recently that I discovered clearly the best producer of Rosé des Riceys, a real step up in quality, initially via this producer’s Champagnes. Olivier Horiot only started out in 2000, and he began by making the still pink before making bubbles. He uses two sites, after which he names his two single vineyard cuvées. “Valingrain” is marl and white clay, “En Barmont” is red clay, with Portlandian elements alongside the village’s Kimmeridgian soils. I’m not going to choose one or the other of these. “En Barmont” is usually described as the more fruity of the two, perhaps plumper in most vintages, whilst “Valingrain” perhaps has more finesse but is more linear in the mouth. Maybe.

What is clear is that these wines are class acts, and seriously under-appreciated by the fine wine fraternity. Olivier makes some very good, distinctive, Champagnes (with quite distinctive labels), the most easily sourced called Sève, and let us not forget two still Coteaux Champenois bottlings, a Chardonnay and a very good red Pinot Noir. But it is the Rosé des Riceys cuvées which are the stars. If you age them (and you really must), they take on that ethereal quality I mentioned with Cédric Bouchard’s “Creux d’Enfer”, but they never lose their classic red fruit character.

My justification for including this still wine in my Grower’s baker’s dozen is that we have just made a journey through many (certainly not all) of the terroirs of Champagne, and Rosé des Riceys reveals so much about the terroir here in the south. We have already vicariously sipped on a dozen wines which exemplify these terroirs. If we really do follow this, or a similar, route we can build up a picture of what Champagne really is, and what it might be.

Why should we bother? Because Champagne should not be dismissed as a drink for celebrations, almost not really a wine at all. Champagne should be appreciated as a wine like any other, and one which partners most dishes at table. If we can begin to appreciate the subtleties of terroir, we can then better understand the good and the bad (and the downright amazing) that exists in the Grande Marque blends as well. Which means we will truly appreciate all that the Champagne Region has to offer.

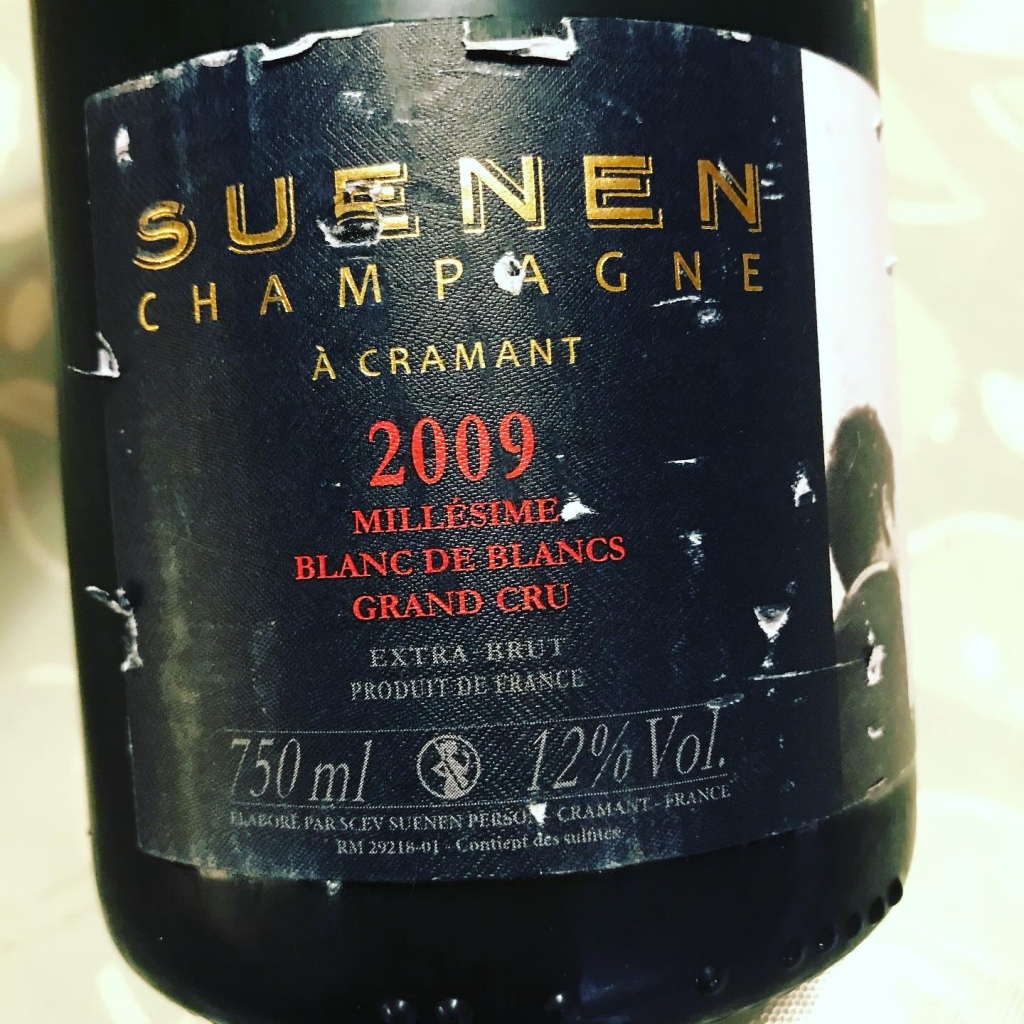

I promised (threatened?) I would include a few more names of producers I particularly enjoy. I could easily list thirty or more Growers here, but that would not be helpful. So, with apologies to any I missed out, I could so easily have included in this hypothetical mixed case Agrapart, Val Frison, Ruppert-Leroy, Aurélien Suenen and Jérôme Dehours. That I didn’t was only due to time and space, or lack thereof.

There are several retailers and direct-selling importers who provide good sources for interesting Champagnes like those listed above. The Good Wine Shop (I use the Kew store) always has enough bottles of good Growers to make it difficult to choose, as does The Sampler. Les Caves de Pyrene is light on Champagne but what they do have counts. Vine Trail has one of the best lists of Grower Champagnes in the UK, Dynamic Vines sells Francis and Delphine Boulard (which you might otherwise be pushed to find here). Horiot is usually well represented at Winemakers Club.

I particularly recommend a trip to La Cave des Papilles in Paris’ 14th Arrondisement. They are very friendly with Emmanuel Lassaigne and as well as stocking his full range (when available), he makes their “House Champagne” under the Papilles label (see photo below). Reims and Epernay are there to explore, with many good Cavistes, but Le 520 (1 Avenue Paul Chandon, Epernay) specialises in Champagnes d’Auteurs, and has a fine range.

I currently use three books for reference on the Growers in the region region: Michael Edwards’ “The Finest Wines of Champagne” (Aurum, 2009); Peter Liem’s “Champagne” (Mitchell Beazley, 2017, which includes the wonderful Larmat maps in a pullout tray); and the entertaining “Bursting Bubbles” by Robert Waters (Quiller, 2017, originally Bibendum Wine Co, Australia, 2016). The literature on Champagne is considerable. For more information on the Grandes Marques I am often inclined to turn to Tom Stevenson, who has written more than twenty books and runs the prestigious CSWWC (Champagne and Sparkling Wine World Championships), a wine competition wholly for fizz.