Two book reviews in a row. I hope that isn’t too much, but with that gift-giving season fast approaching I wanted to get this out there in plenty of time. The Wines of Beaujolais by Natasha Hughes is one of the latest in a series first initiated by Infinite Ideas and now part of the Academie du Vin Library. It joins a roster of essential reading on the wines of the world, whether covering a whole country (The Wines of Austria, Germany, Great Britain etc), a style of wine (Rosé, “Fizz”) or a region, as with Rhône, and Loire, and this work here. There are now nearly twenty books in this series and I have read and enjoyed nine of them so far.

When I first got into wine it was easy to ignore Beaujolais. The “flower label” wines of George Duboeuf were ubiquitous, well made but hardly the most exciting. For those who are rightly about to enjoy this year’s Beaujolais Nouveau, well you might not be old enough to remember how hyped, and often horrible, those wines were in the Nouveau craze of the 1980s. Industrial winemaking was common and terroir hardly considered worth mentioning.

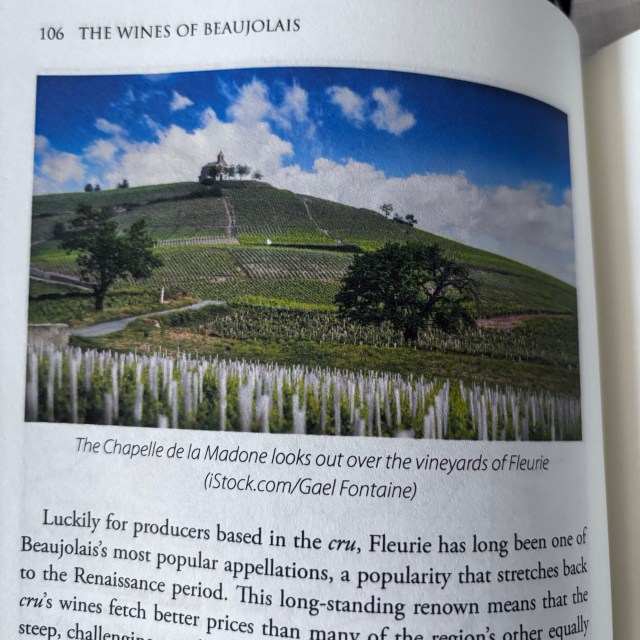

The first thing that piqued my interest in Beaujolais was the landscape. We used to stay on the Côte d’Or for a week each year when we were young, usually Meursault or La Rochepôt, just over the hill from Saint-Aubin. We always made a day trip somewhere. That’s how I ended up falling in love with Arbois and the Jura, but Beaujolais and the Southern Mâconnais were an obvious choice to visit. The hills between Mâcon and Villefranche-sur-Saône are so beautiful that you cannot but wish to explore their villages, their restaurants and their wine.

I also owned a lovely book written by someone more famous as a cricket commentator in my childhood, John Arlott. Arlott on Wine (1986) was more or less a compilation of wine articles he’d written from the 1950s up to the 1980s. I can’t seem to lay my hands on my copy so I hope it wasn’t part of the great cull of books when we deemed 1,000 a generous limit to be moved from Sussex to East Lothian a few years ago. Arlott loved Beaujolais, largely as a bon-viveur, and his enthusiasm was infectious. However, it took me until the 2000s to finally understand what he meant.

All this was long before I had ever heard of Jules Chauvet and natural wine. It was much later, as my eyes opened to natural wines, that I learned how important Beaujolais (with its so-called “gang of four”) was in relation to that movement. Then came my discovery of Jean Foillard. I learned that Gamay’s essence is not what I’d tasted in Nouveau, or negociant Cru wines, but a grape potentially up there with Pinot Noir. Certainly, it is a variety which is capable of ageing, and sometimes, when you do so, you will find it even tastes a bit like an aged Red Burgundy.

I am coming to the end of a vertical run of Foillard Côte du Py which I began purchasing in the late 2000s and stopped regularly buying about six or seven years later. More or less every bottle has been a strong contender for wine of the month in our house. Such wines, especially given their ability to mature so well, do offer amazing value for money, even today, although very few retailers will have the Côte du Py for less than the mid- or upper-forties in pounds now.

Forty is now in my bracket of wines I will only occasionally stretch to nowadays, but in terms of Beaujolais generally, this is not a problem. We have seen an explosion of wines, some from old estates rejuvenated by the next generation, and some from wholly new names who have fallen in love with the region, and it should be said, by the opportunity to buy affordable vineyard parcels. Most of these wines range from good value down to criminally cheap (I use that word because every artisan deserves to make a living and many find themselves sailing close to the wind on that score).

A lot of the most exciting wines today are made by men and women with a better understanding of modern viticulture, health and sustainability. Viticultural, and wine making, practices range from so-called sustainable viticulture through organic, biodynamic to fully natural wine. Very few artisans, or even medium-size producers today go for the full-on chemical dousing which was once normal practice in the region.

Beaujolais also became a happy hunting ground for very small negociant arms of winemakers, usually in Burgundy. The region provides them with the chance to make less expensive wines, but the ones I’m thinking of are still aiming for the same quality focus as their Burgundies, and they often have significant control over how the vines are treated and when the grapes are picked and transported to their wineries. In my case, the Beaujolais wines of the Ozgundian trio, Le Grappin (Andrew and Emma Nielsen), Mark Haisma and Jane Eyre, have all provided me with some lovely, juicy, bottles (and bagnums).

Another major impulse to buy Beaujolais for me was the annual Beaujolais Tastings organised by wine PR company Westbury Communications. In that pre-Brexit, pre-Covid era, they gave the trade an unrivalled opportunity to taste well over a hundred wines, showing the full diversity of Beaujolais from white and pink right up to the Crus. Not to mention the fact that absolutely everyone who was at the cutting edge of wine in the UK at the time, whether importers or retailers, restaurateurs, writers and journalists would all be there.

Natasha Hughes is a Master of Wine and a London-based freelance wine writer, educator and consultant, as her biography says. She became a MW in 2014 and for the last decade has become established as a journalist and a contributor to various books. As far back as two decades ago, she had been section editor for Beaujolais on Oz Clarke’s annual wine guide. She has since become a noted competition judge, as well as being involved in wine education and wine travel as most freelance wine writers are.

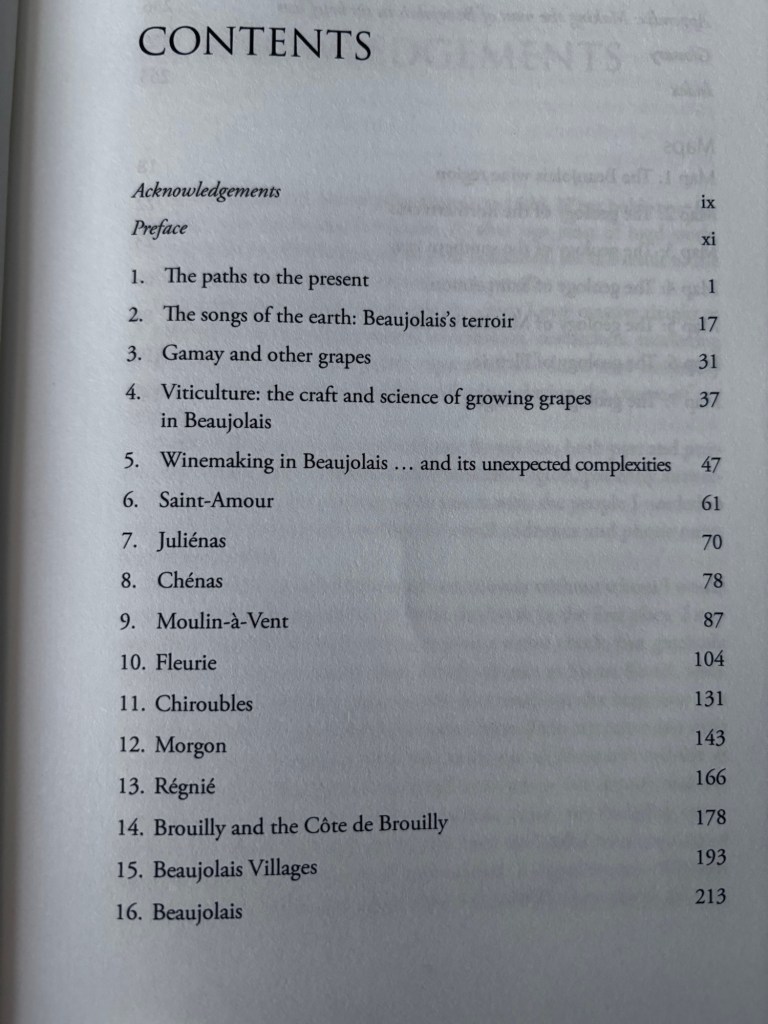

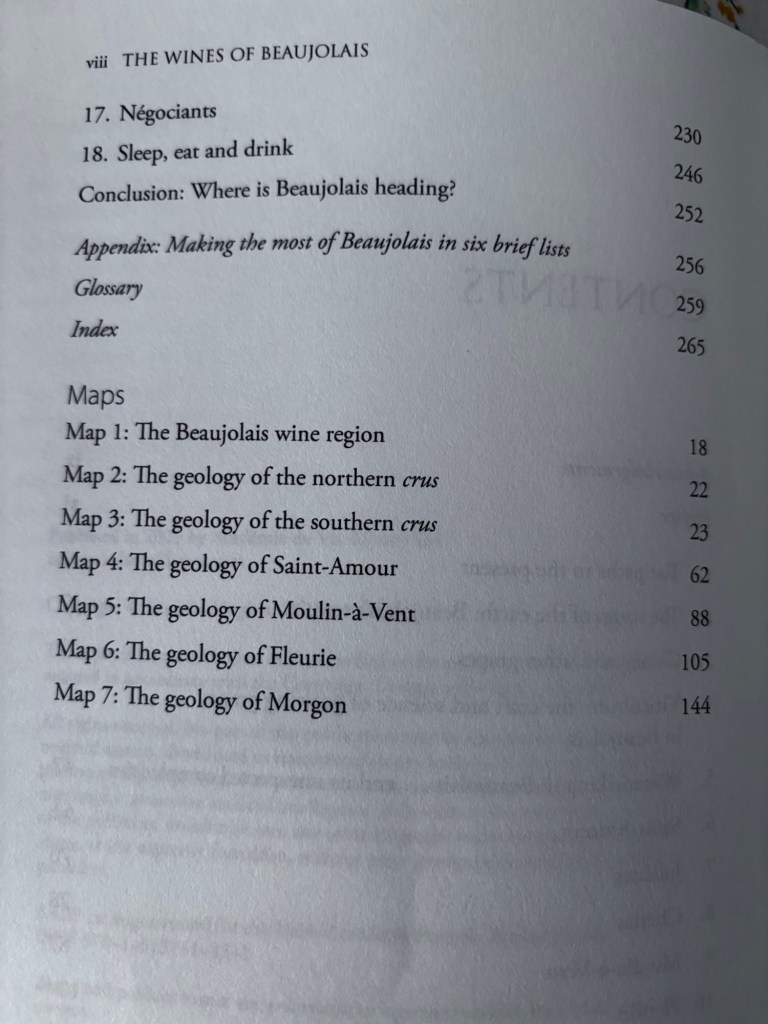

The Wines of Beaujolais follows what is now a well-established pattern in these Academie du Vin Library works, and I shall broadly run through the contents below. However, I want to tell you what I think makes an excellent wine book, whether on a whole country, or whether it’s a regional guide. For me it is simply whether the book inspires me to go out and buy the wine. Naturally it’s about increasing my knowledge, but inspiration to seek and drink is the bottom line.

This book definitely achieved that, and after a bit of a lull in purchasing the region’s wines I have already been scouring merchant’s lists and either buying odd bottles here and there, or making a mental note of where to head when I’m next in London.

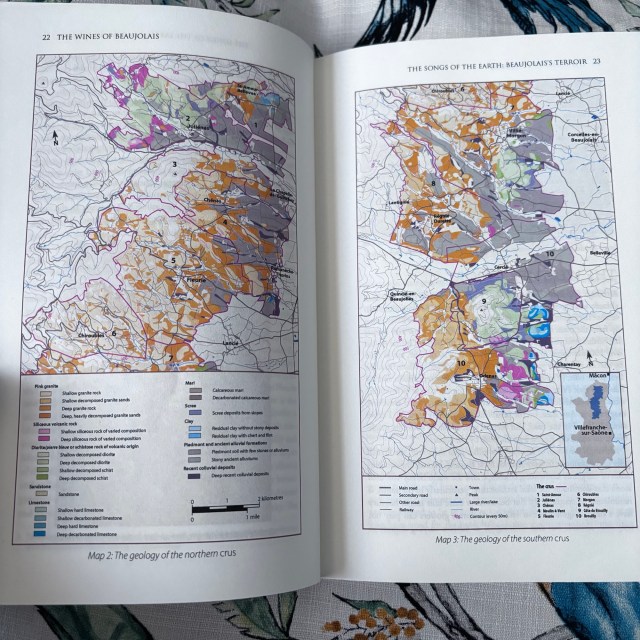

We begin with some history, some explanation of terroir, of grape varieties, viticulture and winemaking. It should be highlighted, when I talk about grapes, that Gamay is not the only variety grown in Beaujolais. Many will know that there’s a lot of Chardonnay. True, most goes into Crémant de Bourgogne (did you know that?), but increasing quantities of still Beaujolais Blanc is made, albeit at a small scale. If I see one from a grower I know, I always grab it. They can be lively and fresh, and of course good value.

We also have plantings of a wide variety of grapes, from Pinot Noir and Syrah to Viognier, Aligoté, Marsanne and Roussanne, and of course some of the new Piwi varieties. Gamaret, so successful in Switzerland, is planted, as is Chambourcin and Marselan. There’s even a little Muscat and Chenin Blanc in the far south of the region.

Of course, only Gamay and Chardonnay may currently be used in AOC/AOP wines, but then increasingly we are seeing wines from the region, especially those made by young and experimental, forward-thinking producers, bottled as Vin de France instead of under the appellations. Equally, you might have spotted that some of the Gamay is going over to the Jura and appearing in various negoce bottlings there.

The bulk of the book takes us on a journey roughly north to south, starting with the ten Crus, followed by Beaujolais-Villages and Beaujolais. Each of the many featured producers appears under these sections, though located under just one, the most relevant to them, when they make wine in different Crus etc.

All of the top producers appear, along with up-and-coming ones, and others deemed important. I couldn’t think of any that were missed. Certainly, those younger producers I really like (both Suniers, Domaine Chapel, Mee Godard, Domaine de la Madone, to name a few) all get glowing reviews.

We also get to learn of the struggles of some to obtain just a few vines to get them started, and of the financial difficulties many in the region face to keep going due to rising costs and the difficulties obtaining a reasonable price for their wine. We also read about other current issues, not least climate change, which has generally negative effects, except in sites where ripening was once highly marginal.

Warming temperatures are finally making some marginal vineyards at higher altitudes viable. Often these contain great old vines. It may not be too long before long-ignored Crus like Chénas, with its steeper hillsides and higher elevations, become fashionable, and some of the Beaujolais-Villages, also with a preponderance of higher-sited vineyards, are knocking at the door of the Crus. It’s a fact that once hard-to-ripen sites are now becoming warmer…consistently so.

These sites also have other advantages alongside vine age. They are often steep and hard to farm, so you need to be young, fit and enthusiastic to take them on, obviously presenting an opportunity for those desperate for a few rows to get them started. Some sites have been sufficiently abandoned for a long enough time that they have not had sprays used on them for a while. If they are too steep for tractors the soils probably show less compacting too. Some of these vineyards are the future.

All of these issues show that the author is not merely going through the same material others have covered, but has written a very contemporary account of what is happening in Beaujolais right now.

The book concludes with a section on the negociants, including those I mentioned above, followed by half-a-dozen pages giving very useful tips on where to sleep, eat and drink from someone who knows the whole region pretty well. Very useful in a region where the landscape of attractive hills and typically attractive villages lends itself to tourism, yet which has until recently been pretty poorly geared-up for it.

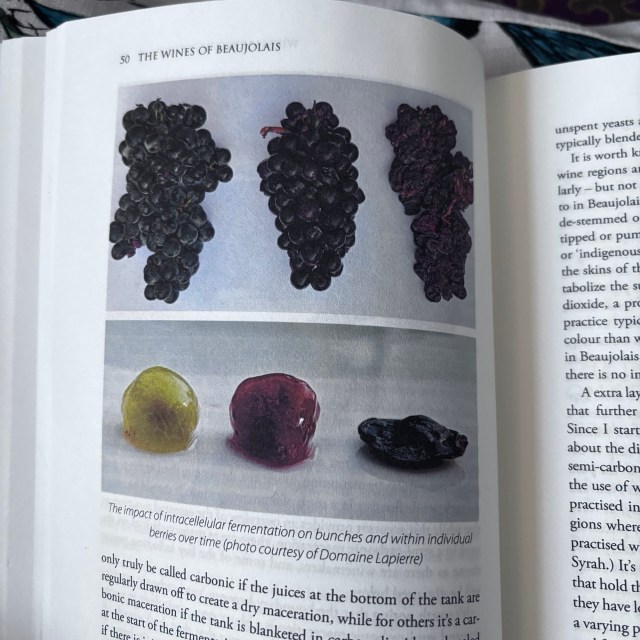

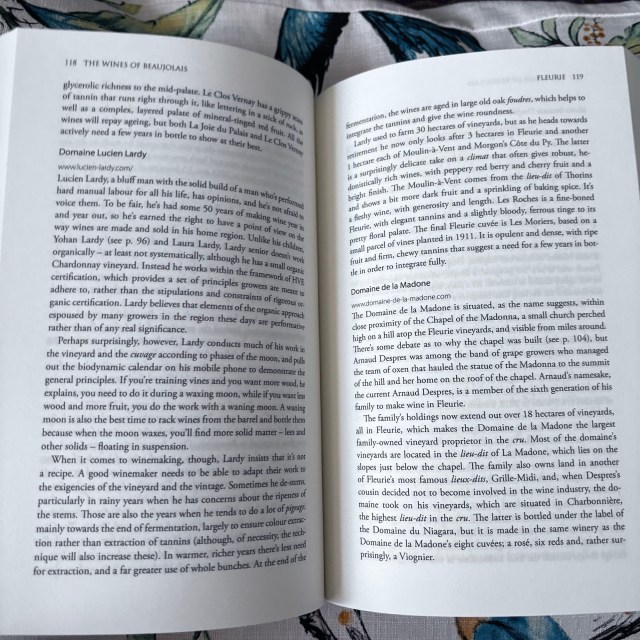

A note on photographs. It was originally the way with these books that you may have had a few black and white photos through the text, plus some tipped-in glossy pages of photos near the middle. The glossies seem to have been done away with, replaced by matt full colour images for maps and photographs within the text. These photos are attractive but also informative, or directly illustrative. Some might miss the glossies, but I think the move is positive, very much so for the maps. The old monochrome was dull.

Natasha ends with an interesting conclusion, “Where is Beaujolais Heading?” Here she sets out a number of very real possibilities as to where we might be in 2045 (Armageddon not included), which range from positive (effectively consumer realisation of how good these wines are) at one extreme, to negative (effectively climate chaos making the region “unviable as a source of high-quality wines”) at the other.

Naturally, Natasha Hughes hopes that her book will help to nudge us all towards the first scenario. To quote the final sentence of her concluding paragraph, “It is my most fervent wish that in writing this book and opening readers’ eyes to the wonders of Beaujolais I may, in a very small way, have helped to skew the probabilities of future events towards the more positive outcomes for the region.”

I hope so too, and if the region has a better advocate in print today, I am yet to find them. This book will ignite, or perhaps re-ignite, your passion for these lovely, versatile, juicy wines. Just fill your cellar before they become expensive, or dwindle away through climate change.

The Wines of Beaujolais by Natasha Hughes is published by the Academie du Vin Library (2025, 270pp, RRP £35 from the publisher, but you may find it cheaper if you are someone who wants to explore other online options). Either way, Christmas Stocking hints start now.