You might well ask why a wine blog has a review of a book about cheese? Then again, you might not. Cheese and wine do bear some notable similarities, in that whilst the majority of both cheese and wine are effectively industrial products, made on a large scale, their artisan counterparts are unquestionably products of their terroir, to a greater or lesser extent. Even more so in the case of natural wine, where minimal manipulation and a focus on minimal natural additives bears similarities.

That said, perhaps such an explanation is superfluous because it is certainly true that most lovers of interesting, artisan-made, and especially low-intervention wines will also have a similar interest in, and in many cases a passion for, those artisan cheeses.

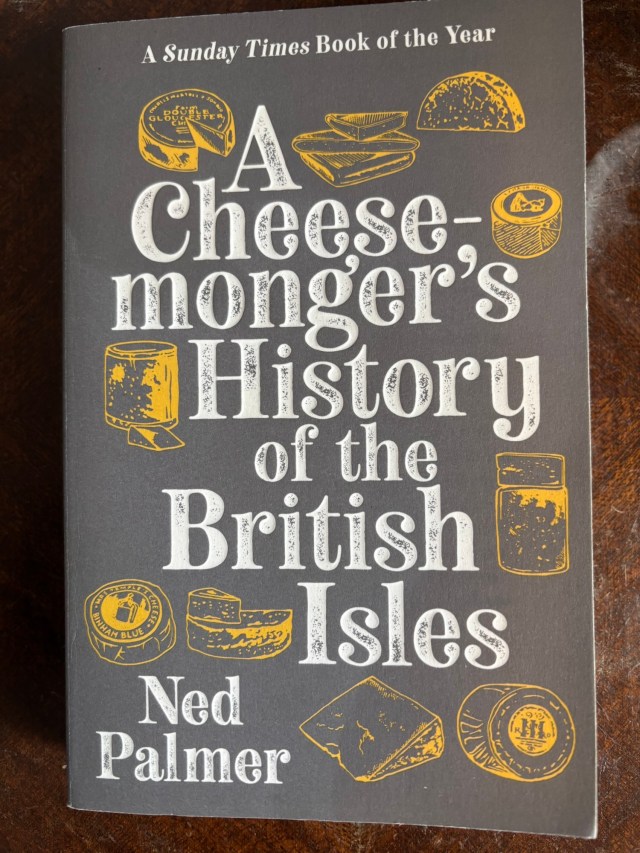

Ned Palmer will be a name to jog the memory of subscribers to Wideworldofwine. It was way back in February 2021 that I posted a review of his book A Cheesemonger’s History of the British Isles. That book was brilliant, telling as it did a history of our islands through its cheeses, from Neolithic times to the cheese renaissance of the last quarter of the 20th Century. I must have liked it a lot (my review says it would surely be one of my books of the year) because I was fairly shocked when I realised it was a whole three years since I read it. No way does it seem that long.

Three years later I am reviewing Ned Palmers latest book, A Cheesemonger’s Tour de France. It follows a loosely similar format to the last book in that the main body of the book gives us eleven chapters on eleven French regions. Each has a main focus on one cheese, although plenty of others are mentioned peripherally. We begin in Seine-et-Marne with Brie, before learning in further chapters about Munster, Époisses, Comté, Salers, Roquefort, Buchette de Manon, Ossau-Iraty, Crottin de Chavignol, the new wave of cheeses from the one-time cheese-free pays of Brittany, and finally Camembert.

Each chapter gives us information about how the cheese is made and what it might taste like at different ages, but we also get history, social history and folk tales woven into the text. Of course, Palmer has a focus on artisan production, whether fermier, or in some cases laiterie, but industrial production is not ignored, even if only to elaborate its negative influence on the AOC regulations, and perhaps on our taste buds.

The author is ever present adding a personal touch. He has a wealth of knowledge and experience which comes through in easy to digest form. I occasionally raised an eyebrow at some of the wine-related comments, but then I know more about wine than Ned does, and he knows a hell of a lot more about cheese. This book reads as a personal travelogue, as he travels through France visiting standout producers in each region, and that makes it more appealing in my view.

The highlighted cheeses are well selected. Some, like Brie and Camembert, are so famous that we might often ignore them in the cheesemongers. That was brought home to me after I randomly decided to buy some truffled Brie de Meaux at Christmas, a contender for my cheese of the year! Others are only well known to those who are serious cheese fiends, like Salers. Others are so much more commonly seen in relatively disappointing industrial form that some might wonder what the fuss is about until they taste a true artisan version, such as Ossau-Iraty made from unpasteurised sheep’s milk up on the estives (high summer pastures).

The book finishes with a short chapter on the future of French artisanal cheesemaking before a directory describing in short fifty-five cheeses, principally those that get a mention in the book as well as those featured for each chapter, along with some further reading and a “how to buy fromage” add-on. I would only suggest “preferably not in a supermarket”, which applies to France, but you can find some edible cheese here, in Waitrose, if you really can’t find a cheesemonger.

In the UK cheesemongers of quality are now fairly easy to find. I am especially lucky to have access to two of Great Britain’s finest within striking distance of where I now live, in Scotland. Ned Palmer gained his stripes working for Mons in London’s Borough Market and at Neal’s Yard Dairy. At least I presume it was Mons as their French business gets many mentions throughout the book. Neal’s Yard Dairy may be better known to most readers, but Mons is truly worth a detour. I remember once being asked what I wanted to do on my birthday and the answer was a trip to Mons.

Any criticisms of the book? Well, no. I mean I risk sounding like a broken record if I mention typos. Editing ain’t wot it used to be. Some books start out all guns blazing but run out of steam, with the author trying desperately to find more to write about. If anything, this one starts sedately and builds up. Perhaps Ned just saved the best until last, as we might do with a cheese platter. I certainly felt he warmed up as he went along, but I’m not saying the early chapters weren’t good. They certainly were. Just perhaps that he got into his stride.

A Cheesemonger’s Tour de France does have some photos scattered throughout the text, but it doesn’t have a nice colour photo to show you what each cheese looks like. For that you would need to go elsewhere. The two books I have found most useful in this regard are:

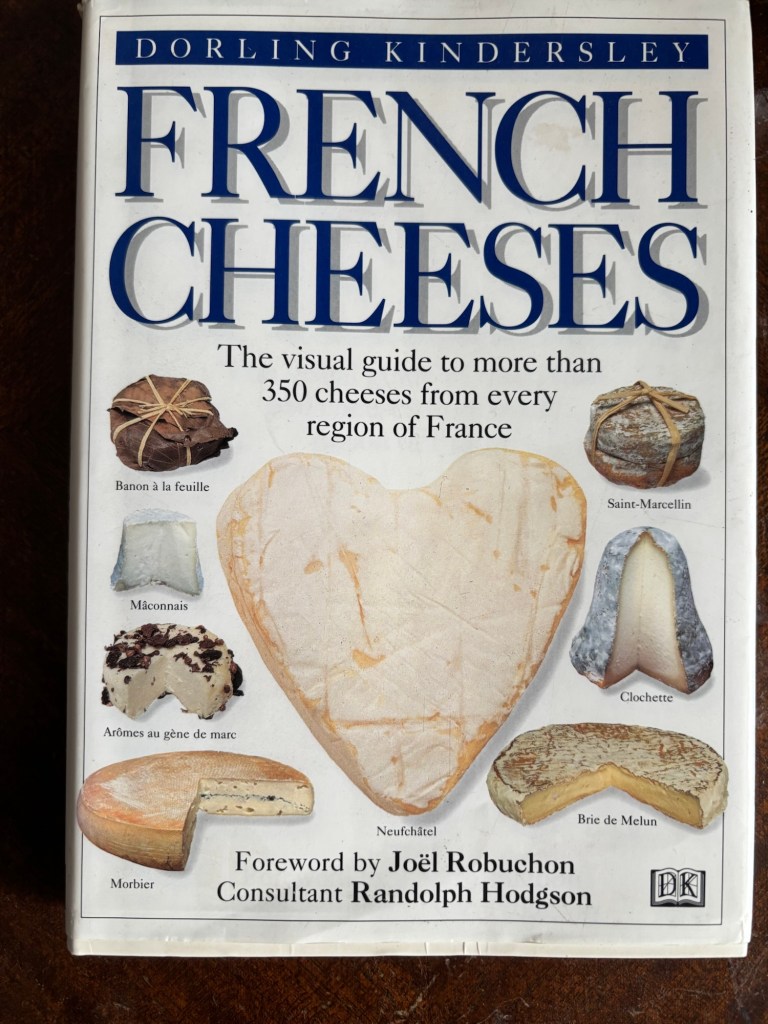

- French Cheeses (Dorling Kindersley, 1996); and

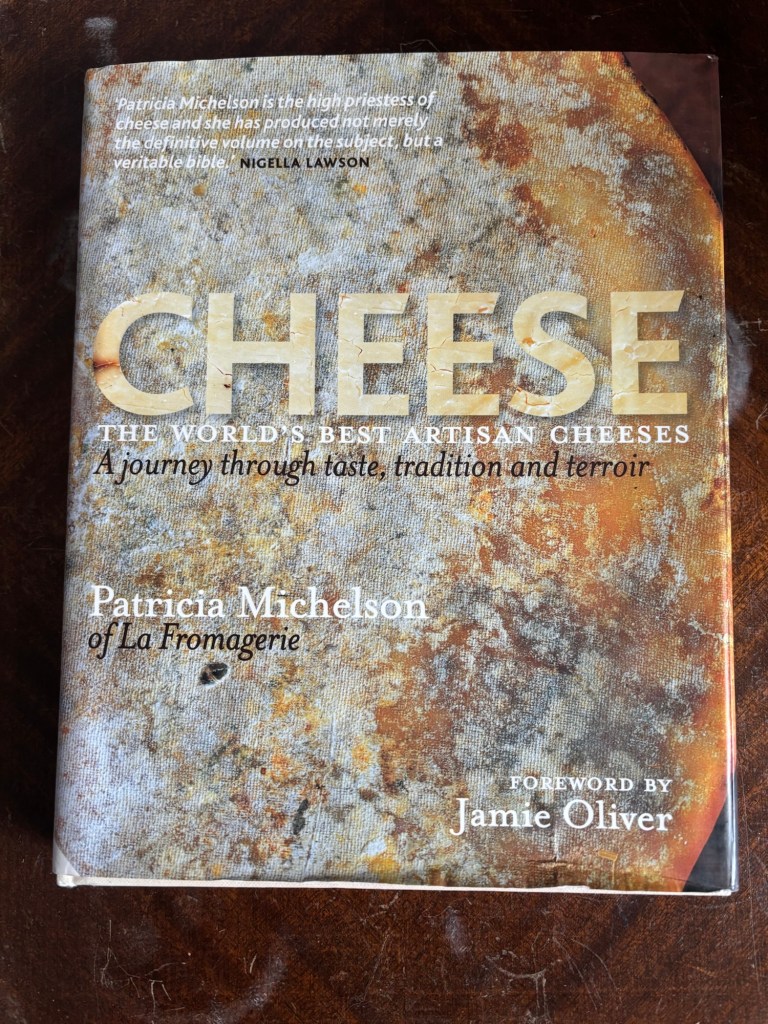

- Cheese by Patricia Michelson (pub by Jacqui Small, 2010)

The Dorling Kindersley book is very visual, with only a small amount of information on each cheese. However, Charles de Gaulle famously said France was a country of 246 cheeses (I think?) and the DK book lists an impressive 350.

Patricia Michelson’s book doesn’t only cover France, but it is a beautiful book and I pull it out regularly (it’s a weighty tome so it probably helps my arm muscles as much as it delights my senses). It is more selective in its coverage, but a little more detailed than the DK, and you get to share in the knowledge and insights of another of London’s finest cheesemongers (Her shop, La Fromagerie, is in Marylebone).

However, these books would be entirely complementary shelf companions. Ned Palmer’s Tour is immersive, as any travelogue should be. It captures more of the essence of each of the cheeses featured by way of their terroir, their social history, and allowing us a glimpse into the lives of some of the characters who have the passion to make these cheeses, for being a cheesemaker is not an easy career choice and the best of them still face tough physical work, grinding bureaucracy and very considerable financial pressure.

Indeed, if there was a renaissance in French cheese at the end of the last century, the first half of this century risks seeing artisan cheesemakers going out of business, as seems to be the fate of hundreds of thousands of farms of all kinds across Europe.

Equally, if you are reading this in the UK and you have ever wondered why European artisan cheeses have increased so much in price, well, like wine, the hassles and paperwork involved in crossing our post-Brexit border (made worse in terms of form filling since 2024), have caused many smaller cheese producers, along with wine producers, to seriously question why they bother.

Still, if this book does anything, perhaps it might do for you as it did for me and act as a prompt to buy more cheese.

A Cheesemonger’s Tour de France by Ned Palmer is published by Profile Books (2024, hardback, 374pp, £18.99).

Ned’s book on British Isles Cheeses (an important distinction as Irish Cheese is included)