Whisky? No, I’m not planning to become a whisky writer now I’ve moved to Scotland. For one, I certainly don’t have the expertise. However, there’s no doubting that once you cross the border whisky becomes part of the culture in a way it isn’t back down in England, even among aficionados. If I do introduce the odd whisky article among the wine, will you forgive me, and will you read them? The world of single malts certainly has some similarities to wine, a differentiated product made from its own natural ingredients but with its own personality, in part derived by its place of production, and also its method of maturation.

Wine for me has first and foremost been about people and places. Visiting vineyards and seeing a wine in its place of birth, so to speak, has always helped me to understand it better. Whilst I’ve been reading the typical encyclopaedia-type books on whisky, to gain knowledge of the processes and individual distilleries (accompanied by a dram, of course), this book, Whiskies Galore, is a little different. As a travelogue, it’s perhaps more like some of the wine books we all know. Maybe more akin to Kermit Lynch’s Adventures on the Wine Route than the Atlas, or Pocket Wine Book style.

Ian Buxton is one of a clutch of well-known whisky writers who began working in the industry, largely in marketing, not far off forty years ago. He was Marketing Director of Glenmorangie, among other posts, starting his own consultancy business in 1991. He began his publishing career in the early 2000s and has written a string of books, including 101 World Whiskies to Try Before You Die (2012, current edn 2022).

Whisky knowledge is all well and good, but you want more from a travelogue. You want both knowledge of, and passion for (and occasionally lack of), the places visited through the landscape, the people, and the culture. This is what you get here, and this is why Alexander McCall Smith says on the back cover “Enthusiasts for whisky will delight in this engagingly written book, but so will others who love the islands”.

I have a confession. I am yet to visit any of the islands which lie off Scotland’s west coast. This is surprising because my wife has connections to Mull and I have wanted to visit Skye ever since a geography teacher described a trip there to our class when I was a teenager. Islay was the source of the first whiskies I fell for, and Islay’s wild west coast is the location of the distillery I have drunk most from, and become totally enamoured by, since I came to live in Scotland. Harris and Lewis were introduced to many of us us by natural wine’s very own Doug Wregg, through his hauntingly beautiful photos on Instagram of Europe’s whitest, sandy, beaches. Then we have the lesser-known islands, such as Arran (I shall buy some soon) and Raasay. It will take many years to explore them all.

Why a book on the island malts? I would guess that, as Buxton acknowledges in his introduction, the island distilleries have gained a romantic image. The trials of living in these wild places, and the peatiness of many of the whiskies produced out on the Atlantic Rim, to which (among others) many newbies to whisky seem partial, give the islands, and especially Islay, a particular lure. Although these islands are without doubt wild and wonderful places which attract tourists for their nature and topography, the main tourist draw, especially for Americans and Northern Europeans (including Scandinavians) is undoubtedly Malt Whisky.

What of Buxton’s writing style? I would say that the book reads slightly as if it were written in another age, yet one which brings us to the near present on the page. What do I mean? Certainly, it isn’t a criticism. The style reminds me of Robin Yapp, who some readers may have come across. Robin set up Yapp Brothers, an English wine merchant specialising in Rhône, Loire, and Provence. Having already mentioned Rhône specialist Kermit Lynch, it should be said that at around the same time, these two men from different continents were travelling unfrequented byways of France, bringing back hidden gems of wines, and getting to know winemakers who were making remarkable wines away from the spotlight.

Yapp writes highly personal prose, and his conservative style belies a liberal approach to life. In some ways Ian Buxton’s prose is conservative, and perhaps you will find in his writing echoes of an age which has disappeared in our frantic modern world. If I do not always agree with his sentiments, or occasionally his way of expression, I thoroughly enjoyed his bringing a landscape to life through a love for its soul.

Don’t imagine, however, that the book is full of whispy whisky writing. Through the evocative prose the author manages to impart all the facts you need, and perhaps imparts them in a way that helps you absorb them more easily than you might from a typical encyclopaedia.

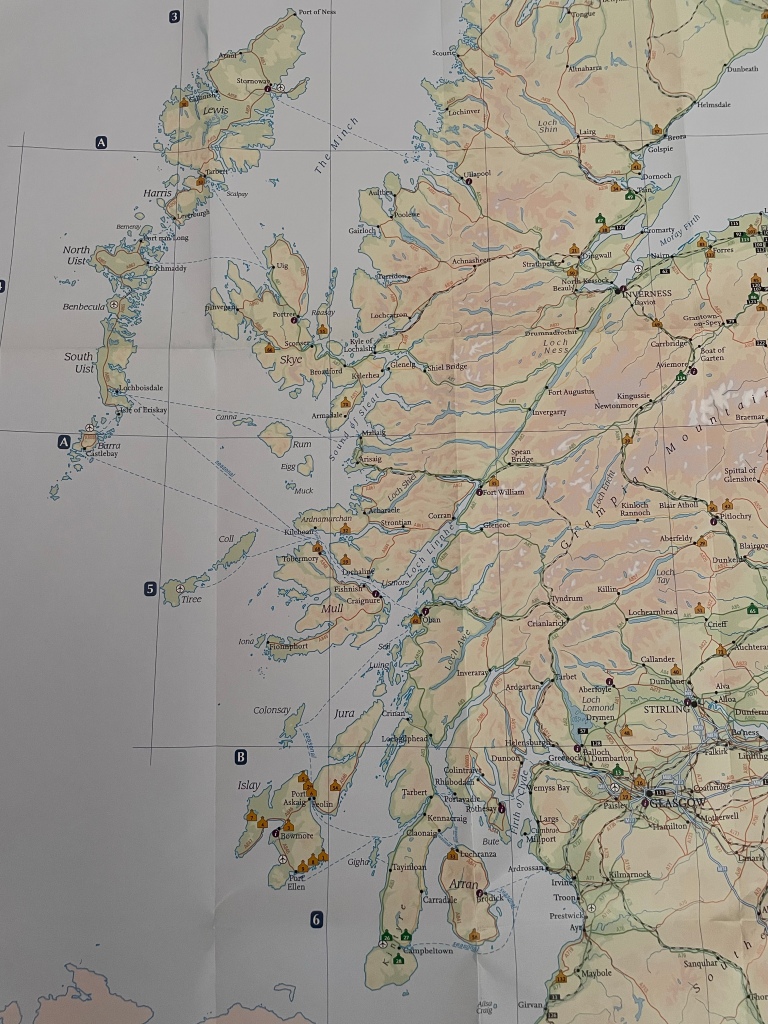

The journey is not quite a straightforward north-to-south one, nor one that is linear in terms of time. We begin in Arran and head north through Jura, Mull, Islay (which fittingly gets two chapters), then Harris and Lewis, Raasay, Skye, and Orkney.

Arran is sometimes called Glasgow’s island by people I know, although it takes more than a couple of hours, including the ferry, to get there. That said, the ferries leave from Ardrossan frequently enough to make a day trip possible, with the Isle of Arran distillery (near Lochranza) a thirty-minute drive from Brodick, where the ferry arrives. Arran is a whisky I’ve not yet bought, but which I’ve been pondering. In that inimitable way that Instagram knows what you are thinking, I’m getting constant adverts for it. It may take me a while to get to Arran itself, but the visitor centre has won major awards.

Islay has long been known to me through Lagavulin and Laphroaig. Lagavulin was introduced to me via the United Distillers’ (now Diageo) “Classic Malts” series, launched in 1988. This original series, which also included Glenkinchie (Lowland), Talisker (Skye), Cragganmore (Speyside), Dalwhinnie (Highland) and Oban (West Highland) did a great deal to promote the single malt whisky concept. We should remember that in the sixties and seventies it was the big blends which ruled the market. There was, surprisingly, no representation in the series for Campbeltown on the Mull of Kintyre, where Springbank is the most famous producer.

Malt Whisky was, of course, the original whisky, distilled often from local crops with a local flavour. The blends were the product of the sixties and seventies marketing ethic coupled with mass amalgamations in the industry (stressing “industry”). This doesn’t mean blends are bad, but single malts, from an identified single distillery, are easy to portray as a craft spirit, whatever their production level. That’s not dissimilar to wine in many respects.

Glenfiddich was bottled as a single malt in 1970, though only at eight years old, but after the success of this product there seemed to be no stopping the single malt explosion. That’s no bad thing for we wine lovers who revel in difference and personality. The Macallan, Glenlivet and Glenmorangie soon followed. But the promotion behind the “Classic Malts” series in the late 1980s was instrumental. I won bottles of Oban and Lagavulin in one of the competitions UDV held.

Islay still holds a greater place in my heart than any other island, but now it is via another distillery, Kilchoman. Established only at the end of 2005, this small “farm distillery” is right over on Islay’s western coast, on the wild Machir Bay. Called a farm distillery on account of it using local grown barley, the private owners of Kilchoman managed to purchase the farm which supplied them, on whose land the distillery was conveniently located, in 2015. It in fact produces 25% of their barley requirements, that barley being malted on site. It goes into their product labelled “100% Islay” malt.

Like many distilleries now, the range is widened by whisky finished in a selection of specialist casks. Sometimes Oloroso Sherry, sometimes Bourbon, sometimes Port and so on. Each year Kilchoman has one or two special releases. For 2023 there’s a Cognac cask release, and Loch Gorm, their peaty malt, has an Oloroso finish. Speaking of cask finishes, I was looking for Arran’s Amarone cask release, only around £10 more than their standard 10-y-o, but sold out, at least in the outlets I know.

The cask finish does affect the flavour of the whisky. Charles Maclean (Whiskypedia, 2009 revised 2022, Birlinn Ltd, Edinburgh) suggests 80% of a whisky’s flavour can be derived from the type of cask it is matured in, which not only includes what it was originally used for, but also whether of American or European oak (American oak still dominates in general with European casks skewed more towards the specialist releases, I think).

My taste for Kilchoman is personal. Something just clicked with me, both the story and the whisky’s flavour. This is mostly not too peaty but balanced, sweet, smoky, and quite fruity, although it is perhaps silly to generalise over several different Kilchoman bottlings. They all finish with that classic Islay salinity, to differing degrees. How could a whisky made on Great Britain’s Atlantic Coast not taste salty?

Islay has, I think, a total of nine distilleries at the moment (more are always being planned, whether in reality or in someone’s dreams). I’m also quite taken with the B’s – Bruichladdich and Bunnahabhain, the former in its garish turquoise bottle in its “classic” format, which initially put me off but now quite appeals. Jura, just over the water from Islay, has one distillery. I really should get a bottle, given my passion for the wines of its French namesake.

Another island with one distillery is Mull. Until fairly recently the distillery at Tobermory, Mull’s famous, colourful, largest settlement, did not have a good reputation. However, things have changed here since a major upgrade which led to its closure for a time in 2017. They, being new owners the Distell Group, make two malts here. Tobermory is unpeated and Ledaig is quite heavily peated. The revival of this distillery is welcomed by me because my wife’s father once worked on the island as a young man, and a visit there has been planned for some time.

Of the other islands, Skye has Talisker, which must rank among the most famous of the single malts to those who have some interest in the genre, along with Torabhaig, a distillery located in the south of the island, near Armadale. This was recently restored and released a single malt, which I have tried, in 2021. Just over the water from Skye’s east coast is the small island of Raasay, and the distillery of that name is another which only went into production in 2017. The first home-produced malt began to be marketed in 2020, with positive reviews.

Who wouldn’t want to visit the co-joined islands of Harris and Lewis if they happen to follow Doug Wregg (of Les Caves de Pyrene) on Instagram. The beaches there stretch with pure white sand (on account of their great age) for miles along the Atlantic coast. On Lewis you have the famous Stones of Callanish, perhaps the greatest draw here for tourists on what is the largest single island land mass (other than Great Britain itself and Ireland) of the British Isles.

Of its two distilleries, one is on Lewis and is called Abhainn Dearg (apparently pronounced Aveen Jerrak!). This may be the smallest in Scotland, and Ian Buxton tells a funny tale of his visit there. The other distillery cites its location as Harris, and indeed it is on Harris, if only just, at Tarbert, where Harris and Lewis are cojoined by a narrow piece of land. Isle of Harris distillery calls itself a “social distillery”. It is closely linked to the community. It produces a tiny amount of whisky which is matured in Bourbon and Sherry casks on the wild Hebridean west coast, deliberately to endure the spray of the Atlantic storms.

I have yet to taste this whisky, but the distillery has in the meantime become the producer of one of the UK’s finest gins. It is easily available in Edinburgh, thankfully, because the thought of being buffeted around in a small turbo-prop to Stornaway, or worse still, braving the ferry over The Minch from Ullapool, does fill me a little with dread. Doug doubtless has a finer constitution (or maybe a cooked breakfast and a couple of drams help, I must remember to ask him). If that is at the limits of my bad weather tolerance, then Orkney may be beyond it, but there is a famous distillery at Kirkwall, namely Highland Park. It’s a fine whisky, especially its older renditions.

The author saves Orkney for last. He introduces the chapter by saying “I never came to Orkney as a child…but I have come to love it. It’s perhaps my favourite of the islands that I’ve visited, though I return happily enough to all of them and I’m aware that there’s a lot of Orkney remaining for me to discover”. Perhaps I need to brave-up!

If you want a book which digresses, this is one, and in no place more so than Orkney, where Buxton goes off on a fascinating tangent about boat building. Boats are important to Orkney both past and present. Despite the island’s remote location when viewed from the south, Kirkwall has now become a major stop for the cruise liners. Highland Park has benefited, but so has Scapa, a much smaller distillery now owned by Chivas Brothers, which overlooks the famous naval base at Scarpa Flow. Wealthy cruise passengers like nothing better than to shop when they hit dry land, and as Buxton tells us, this has strangely transformed Kirkwall’s main street.

Buxton also details how the cruise ships tend to ban the bringing of alcohol on board (because doubtless they wish to sell their own at much inflated prices). This has led to the distilleries selling large numbers of smaller format bottles which can be more easily smuggled aboard. It is funny stories like this which make this charming book so entertaining. I enjoyed it the first time and I suspect I may read it again before very long.

If you are seriously into whisky then a travelogue around Scotland’s island distillers may offer something a bit different. If, like me, you are relatively new to whisky, or at least a more serious appreciation of it, then Whiskies Galore will take you beyond a mere factual approach littered with information about Lauter mash tuns and levels of peatiness (measured in ppm phenols). It may not make you a technically proficient taster, but it will help engender a warm passion for the places where this special spirit is made.

Whiskies Galore by Ian Buxton is published by Berlinn Ltd (hardback 2017, reprinted in p/b 2021). RRP £9.99. It seems widely available up here in major book stores as well as good independents.

The map (highly recommended) is Collins Whisky Map of Scotland (2021 reprint).

Whilst good whisky is available from some very fine specialist stores, even the major supermarkets will have the product of many of the whiskies mentioned because a good number of them, despite their individuality and quality, are ultimately owned (and I should say supported to the tune of millions of pounds for development) by large drinks conglomerates. Malt Whisky is now big business, and very profitable, but it is still a fine drink.