It’s what we do, isn’t it? As wine lovers, obsessives even, we visit vineyards and taste the wine, and if we are not the victim of airline baggage restrictions, we probably buy some to bring home. If we are lucky enough to be driving, we bring lots home. Although our partners and children don’t always appreciate our obsession, for those of us who have a wine passion, bringing home bottles from producers we’ve visited on holiday is probably (don’t tell the family) the most exciting part of the trip.

I’m pretty sure that I’m far from being alone here. The fun is partly in obtaining bottles you might not be able to get back home, something the importer thinks won’t sell, but for the self-styled connoisseur it’s just what he or she had hoped to get hold of. Sometimes it’s just bagging new cuvées or vintages which have not yet reached our shores. There’s also the fun of cramming it all in, along with the luggage, and all that paraphernalia you need to give the young ones in the family a sense that it is a holiday for them too, not just a period of automobile incarceration for the length of daddy’s wine trip.

Of course, I’m being a little tongue-in-cheek. Wine regions surely vie with the mountains as the most beautiful places to holiday and the vineyards I love to visit are usually near to mountains, or at least pretty big hills. Can you beat a vineyard walk after breakfast? And on the subject of food, it is probably no coincidence that wine regions also seem to have the best cuisine, at least in Europe.

Such holidays always excite the organisational side of my personality. I like a good puzzle and fitting wine into an already crammed boot is a challenge I’m up for. When the children’s feet didn’t reach the floor in the back of the car, the seat wells could take the odd six-pack for them to rest upon. Odd bottles fit under seats and it is amazing how many small spaces there are in the boot. Mind you, I remember one particular holiday, many years ago now, where we ended up in the mountains near Aosta and I genuinely thought I’d broken the back axle, which had it been true would have been a mean feat for a Volvo estate.

So, if the “wine visit” is the highlight of our holiday, we also assume that it’s part and parcel of a day in the life of your average wine producer. This assumption, or not so much an assumption but something one probably didn’t really think about, has been rocked somewhat over the last eighteen months or so. The issues around visits were first mentioned to me in conversation with Wink Lorch, who highlighted the difficulties even she, as an established authority on Jura and Savoie, was sometimes having in gaining appointments in these regions.

The issue was once more brought to light on social media this month, with some Twitter users apparently declaring their God-given right to rock up at a vigneron’s house, expecting a tasting. The overall opinion went along the lines of “well, they are running a business”. Such a view was somewhat countered in a great piece by Hannah Fuellenkemper, which appeared a week ago on Simon Woolf’s “Morning Claret” site.

It’s a fun read and it puts across the potential point of view of the winemaker very well. In examining all the reasons why someone decided to become a winemaker, she says “but I bet at no point you decided to make wine because you wanted to spend all your time drinking with random people in your kitchen”.

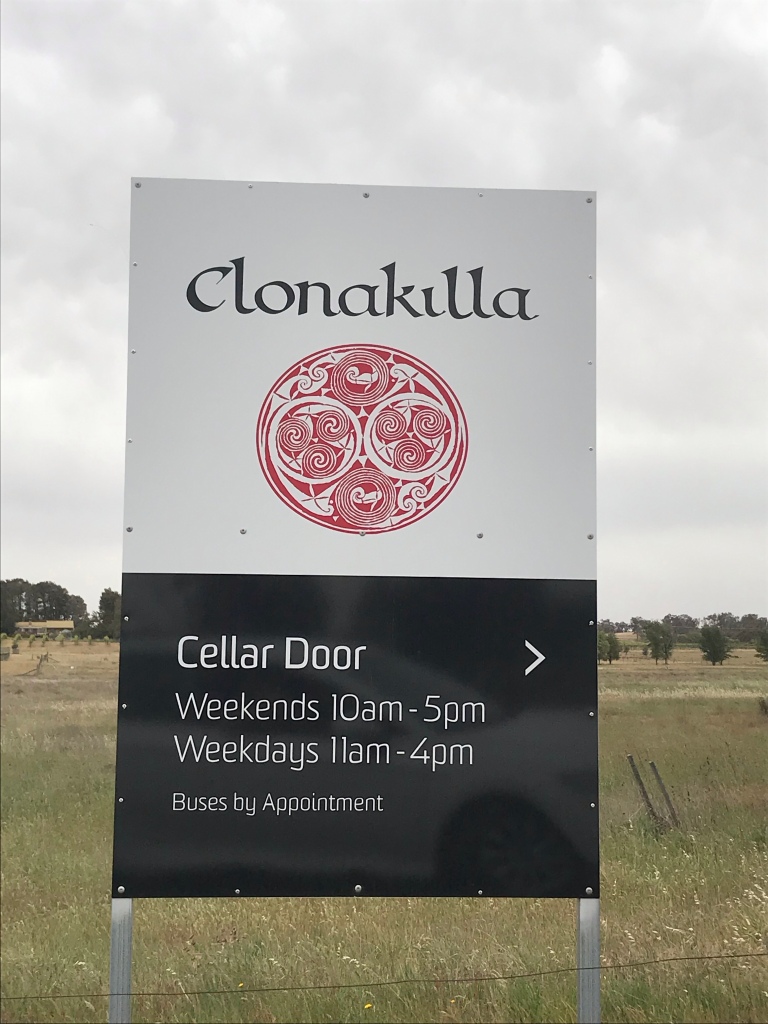

Shall we take a step back. There are many kinds of winemaker and a great number positively encourage visitors. They may be a large commercial operation where coaches are welcome. They may merely be Australian. I jest, but Australian winemakers with almost all sizes of vine holdings will have a tasting room. Those who don’t are highly adept at making their winery very hard to find (even if one has been granted an invitation). Even a star producer like Clonakilla in Canberra District will allow the odd coach by appointment, though.

The finest estates in an Australian wine region like the Hunter Valley, or Mornington Peninsula see the value of wine tourism in helping to establish both their own brand and that of their region. You can expect a tasting room which, these days, will often be modern and light, and there’s a good chance you’ll find a restaurant too. There will be staff employed just to conduct your tasting and the punter will usually be expected to pay a small fee for the samples, albeit usually refunded against a few bottles purchased.

In Europe this kind of experience used to be most common in Champagne. You pay for the “tour” of, if you choose well, some beautiful chalk Crayères in Reims, with a man in period costume, circa 1920, riddling a few rows of bottles by hand (the mechanical gyropalettes which jerk the sediment down the bottles in their millions will be behind closed doors but the keen-eared visitor will hear them clunk every so often). At the end of the tour your fee will include a few sips of the non-vintage.

I’m not knocking this at all. In fact, everyone should pay such a visit. It’s worth it at houses like Taittinger just to see the magnificent cellars. But these tours are not aimed at serious wine lovers. Such tours are now even available in Bordeaux, last bastion of the verb “to exclude”, where the public have generally been excluded in the past and the wines have therefore become even more exclusive.

Today, Bordeaux has opened up. Of the tours available to the general public, perhaps one of the best is to Château Lynch-Bages, in the “wine destination hamlet” of Bages. Bages has a nice place to eat, a top bakery, and on the opposite side of the square, the Lynch-Bages gift shop where, trust me, it’s impossible not to spend some money after the winery tour (the Lynch-Bages Blanc I grabbed on my 2015 visit was actually rather good).

There are many thousands of family producers who fall into the next category, where there’s a tasting room either open at certain times (weekends, open days), or maybe by appointment. If a producer has a tasting-room you can be pretty sure they welcome visitors, though perhaps more at their convenience than yours. Quite often it may be another family member who is on hand to welcome you. A daughter back home from studying English in Boston, or the vigneron(ne)’s partner. You can find such places all over viticultural Europe, from Alsace to Piemonte and from the Rheinpfalz to Burgenland.

Usually, if you’ve called in advance, you will get a welcome, although the article I referred to by Hannah Fuellenkemper is actually titled “Why French Winemakers Never Reply to E-mails”, and the title is apt. They really don’t, and why would they? Don’t imagine you are not one of dozens of people at least who every week crave an audience with the great winemaker him/herself. I always recommend telephoning.

If you don’t speak their language, you may well be, as they say down here, stuffed. My wife speaks the kind of French which sounds French, fluent but with just enough of an English accent I’m told is appealing to the ear (unlike mine…I can get by very well so long as no one mentions my accent). This is a bonus for me, and indeed occasionally for friends who request a favour.

A welcome may not always be forthcoming because life can move at pace for these families. I remember a visit with my own family in tow, arranged with one producer during our drive back to England. We turned up at the appointed time to discover he’d gone out to his furthest vines and we were met by his wife, in her dressing gown (late morning), wholly unaware of our visit. She did open something, but I think she was pleased we were just most interested in relieving her of a mixed case. A relatively short visit seemed in everyone’s best interests.

The difficulty, for the potential visitor who exhibits even a mild obsession with wine, is that Europe’s wine regions are increasingly peopled by very small producers who farm a hectare or two, often with no full-time help. These are the young stars we increasingly chase after, and as the classics of Burgundy, Bordeaux and Barolo become too expensive for most of us, and as natural wine gains even more appeal, more and more of us want to seek them out.

Their partner may do the accounts in the evening or weekends, but there’s no tasting room and no-one to conduct a tasting. These are the producers Hannah is talking about in her article. If you like natural wine, then almost all of the producers you desire to meet and taste with are likely to fall into this category. The issue has been highlighted on social media especially in regard to Jura producers, but the problem is not restricted to that region in France, and not to France exclusively. It is a big problem for the young winemakers who are struggling to make a living from a few small parcels anywhere, but mostly in Europe.

A good example of this kind of winemaker was mentioned in the Twitter feed which led to Hannah’s “response” article. Patrice Beguet is based at Mesnay, a small village which is walkable, being just down the road, from Arbois, Jura’s heartland. I’ve visited Patrice a few times and any tasting he conducts takes place in his small cellar, below the house. Any transactions are conducted in his open plan living room above. Such producers are not geared up for wine tourism and it is hard to believe how an exciting young vigneron like Patrice, whose vignoble includes plots in far-away Pupillin, could actually get any work done if he saw all the visitors who would like to taste there.

Then there’s the elephant in the room…wine to taste? What wine? Many of the people who left comments on the article, and those who commented on Twitter, say the same thing. At the end of the day, wine is a business and if you make wine, you’ve just gotta go out and sell it, boy! But the key lies in whether you’ve got any wine to sell.

Some people forget, or have no idea of, the size of some domaines in regions like the Jura, the Ardêche or Alsace. If you’re a cult natural winemaker worldwide demand strips out your production before it’s seen the inside of a bottle. I know some lucky souls who could double production and still sell out in a week or two, as indeed is quite common in Burgundy as well. These guys aren’t trying to ship hectolitres to China, but anyone who’s been to Tokyo in the past few years will see where a lot of natural wine is heading, especially now that the post-Brexit paperwork or other hassles make my own market such a pain to ship to. The more new markets open up, the less wine there is for us.

Perhaps the extreme of this can be found almost on my own doorstep with Tim Phillips’s Charlie Herring Wines in Hampshire. September will see a tranche of Riesling released. Even at one bottle per customer, he will be over-subscribed, and he could probably double his prices with no change in the result.

You may be lucky enough to sell all of your production from a good year without difficulty, but if you are cursed with having vineyards in much of France, especially Central and Eastern France, you’ll have been greeted with either terrible frosts, or hail, or various kinds of rot, or all three, in pretty much every vintage for the past…well almost as long as I can remember.

Take the case of Patrice Beguet, of whom I spoke above. When I first visited him, it must have been almost a decade ago, he let me taste a whole range of cuvées, dark red, light red, white (oxidative and ouillé), pink, orange and a few petnats as well (not forgetting the Macvin!). I’ve just last week purchased a new wine of Patrice’s called “Three Views of a Secret”. Devastated harvest conditions in 2019 saw his mates Benoît Landron, Claude Ughetto and Marc Humbrecht help him out, and “Three Views” is the result. Without friends like that one wonders whether he’d have enough cash flow from his own vineyards to continue.

Some producers have made a real name for themselves from their negociant wines (Alice and Olivier De Moor in Chablis, Alice Bouvot at L’Octavin in Arbois and J-F Ganevat down at Rotalier to name just three). But make no mistake. The catalysts for creating these labels have been the vicissitudes thrown at them by the weather.

This is happening every year now, especially in and around Arbois. It’s not one bad harvest but several. I know winemaking couples where one has had to go out and get another job to bring in a little more income. Life is tough, and you will know just how tough if you read my June article on the very sad loss by suicide of two of Eastern France’s truly great winemakers (though I don’t wish to judge or to over-simplify the reasons for those tragic deaths, which are not directly related to the contents of this piece).

So, you say, what’s the point of your article? Well, I’m not the kind of person who thinks they can tell others how to behave. If you think these guys are there for your entertainment, or your determination to bag that Vin Jaune their importer doesn’t get an allocation of trumps everything, then that’s up to you.

What I want to do is merely to make my readers pause and think about the situation these incredibly hard-working people find themselves in. Time poor, worn out not just by vineyard work but by the whole commercial/admin side of their business, and with an empty cellar. I have been truly honoured on occasion when I realise that the few bottles a winemaker has agreed to let me buy actually come from their own private stash. That has happened at one producer on two consecutive visits.

How do I propose to change my own behaviour? I think I’m going to seriously curtail my visiting in the case of these very small producers who don’t have a tasting room regularly open to the public. I’m going to stop and think about the impact of my visit. Sadly, this means there are people I’d truly like to revisit but on the whole, I may not feel I can justifiably bother them anymore. I would even say that I feel a degree of guilt for past visits…for my assumption that even as a writer with a wide readership, I have some right to take an hour of their precious time.

This still leaves a group of producers I know quite well, or at least a little. Mostly people in Alsace, Jura and Burgenland who I’ve already visited, chat with on social media and see at wine fairs. I feel pretty certain there are nine or ten places where I am genuinely welcome in those regions. In some cases, I’ve championed their wines from the beginning and they remember that.

I’ve never had the stamina for five visits in a day, like some people, so if I can see three or four producers on a week-long trip, that’s enough. Plus, those who maybe say at a wine fair that I must go and visit them. It does happen, and I’m quite happy to remind them of it. You have to be prepared to take rejection though. I’m not like these “top” journos who believe they can dictate a date and time of arrival, turn up three or four hours late, and still expect to be treated like a king.

Even the hard-working winemakers usually get away for some kind of holiday in August, and equally, hassling them around harvest is usually unforgivable (though again, generosity abounds, as it did with one producer I know well, who honoured our appointment even though it turned out to have been made for the first day of an unexpectedly early harvest, and there was a team to manage. If she was stressed, we didn’t see it).

It’s really just a question of being more thoughtful.

Oh, and one more thing…Hannah says “sometimes people bring gifts”. She also points out the other side of the coin, that some expect an aperitif, or even an invitation to stay for dinner (and it’s true, I’ve heard stories). Winemakers do love trying new wines. Some will have a row of bottles from around the world in their cellar. If you take a carefully selected bottle or two as a gift, you will more than likely find your generosity is rewarded, perhaps with a free bottle yourself, but mostly with a better, more relaxed, visit and the chance to at least buy a few coveted bottles. I’ve done this myself, not at all out of any expectation of reciprocity, but out of a shared passion and respect for the winemaker and empathy for their work.

At the end of the day, it’s all about empathy, isn’t it!

Hannah Fuellenkemper’s article in The Morning Claret can be found here.

Excellent article.

A visit to a domaine can shed so much light & understanding about the wines made.

Consideration towards the winemakers’ workload is key. Of course, from their perspective winter is the best time to host visits, where as most of us wish to visit during the summer, when they are hard at work in the vineyard. For the large producers, there is less of an issue.

I fortunate in having the flexibility to provide the option of joining another group, which is accepted quite regularly. Saves time for the domaine & for me there is the benefit of hearing the opinions of others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also think being a regular visitor helps as after a few visits they know you (and if they don’t like you they can make excuses). You have a big advantage there, in Burg.

LikeLike